In the weeks after the October 19, 2015, general election, Samara Canada, a national charity, surveyed 2,030 Canadians about the recent campaign. The survey responses were analyzed by age: 18 to 29; 30 to 55; 56 and older. Samara’s October 2016 report, Can You Hear Me Now?, explores how Canadians of different generations experienced the election. They were asked about whether they discussed and shared their experiences and thoughts. As well, they were asked about how much or how little parties and candidates contacted them. This article is adapted from the full report, which can be found here.

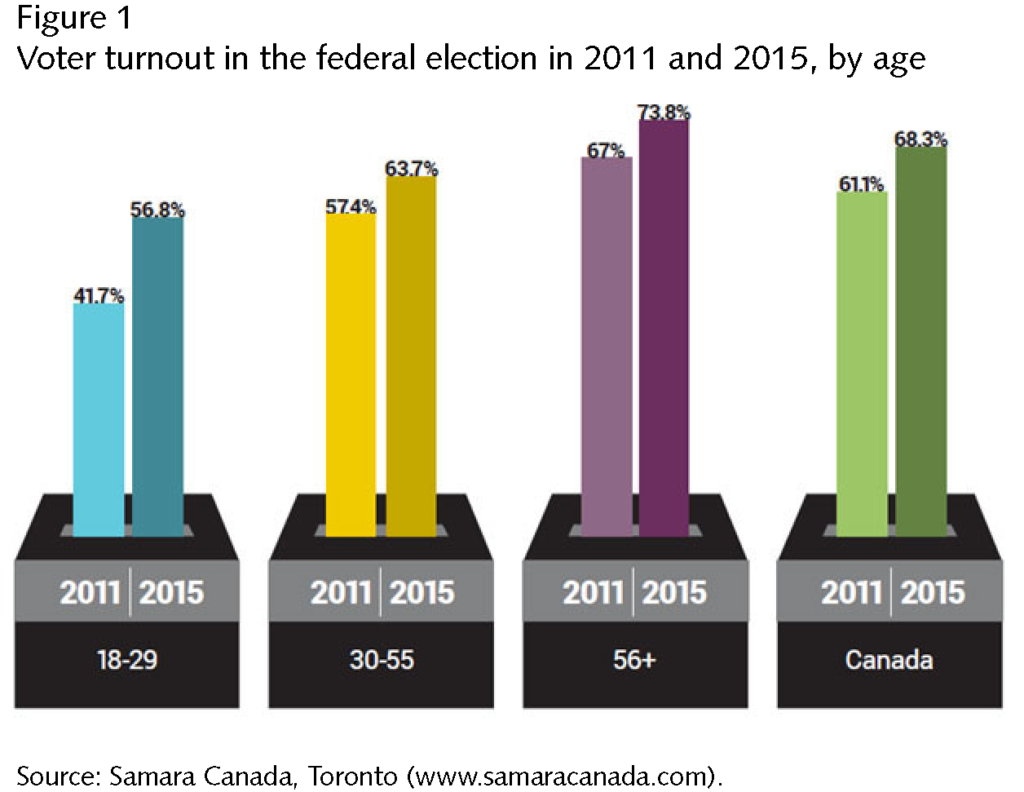

The 2015 election reversed a 20-year decline in voter turnout, bringing overall voter turnout from 61 percent in 2011 up to a surprising 68 percent. While all cohorts saw an increase in turnout, the 18-to-29 age group saw the biggest change, from 42 percent in 2011 to 57 percent in 2015 (figure 1).

Many factors combined to get Canadians to the polls. Canada had its first fixed election date and an extra-long, 78-day campaign, giving people ample time to realize there was an election taking place and familiarize themselves with parties, and with their leaders and candidates. For a long stretch of the campaign period, the three major parties were in a neck and neck (and neck) race across the country, according to public opinion polls, leading Canadians to think something important was at stake. Additionally, more advance polling locations were available and Elections Canada had its largest pilot of voting services on campuses, making voting easier.

Two other factors often play a part in getting people to the polls: contact from someone asking them to vote and the pressure that friends and family exert when they share that they voted.

In Can You Hear Me Now? Samara looked at how the different generations discussed politics and shared their voting experience, thereby potentially influencing each other to get involved. Second, we examined — by both channel and content of discussion — how different generations were contacted by parties and candidates.

How Canadians talk about Politics

While generations of Canadians have been advised to never discuss politics in polite company, during the 2015 election young Canadians ignored that advice, getting into discussions with friends, family and colleagues. Youth were actually the most likely group to discuss politics during the 78-day campaign period: 72 percent said they discussed politics, compared with 62 percent of those aged 30 to 55 and 58 percent of those 56 and over.

Samara’s previous research into how young people engage in politics showed that young people were willing to protest, boycott and especially talk about issues that concerned them at higher rates than older Canadians. This report shows that young people were also more active conversationalists than older Canadians during the election.

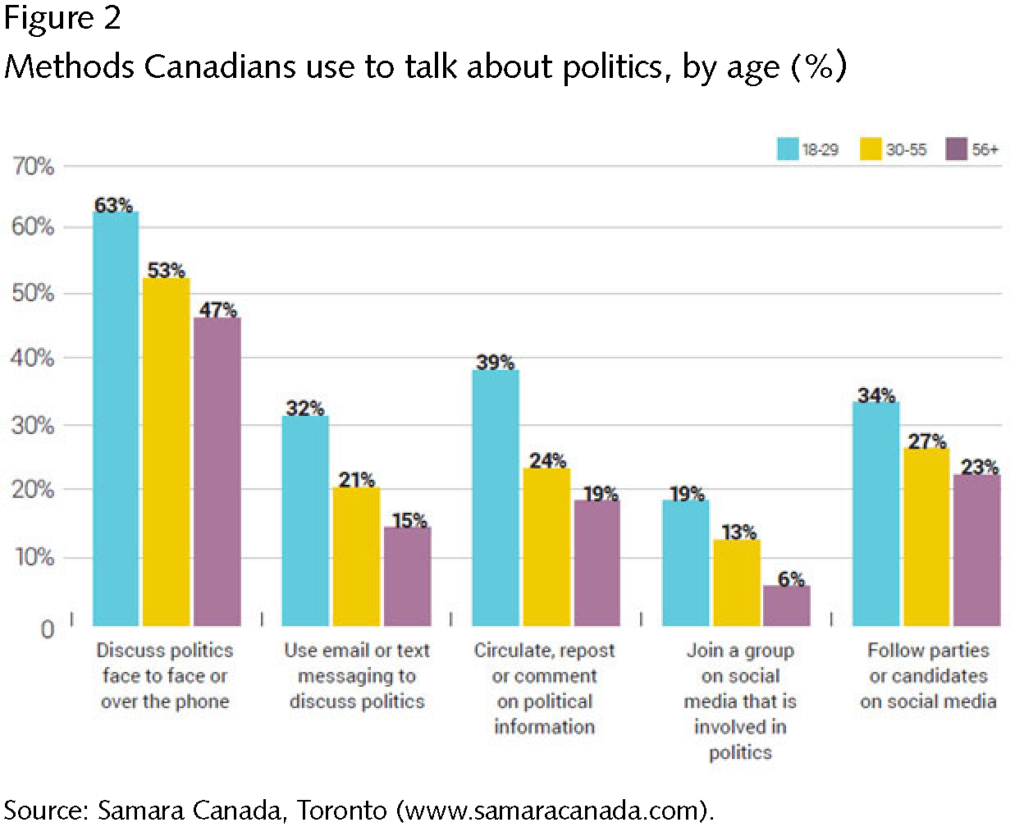

Contrary to expectations, young people weren’t only engaging online: young people reported the highest rates of contact offline, with 63 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds saying they discussed politics face to face or on the phone. Across all five forms of discussion, young people reported speaking about politics the most (figure 2).

Sharing is not just for Facebook

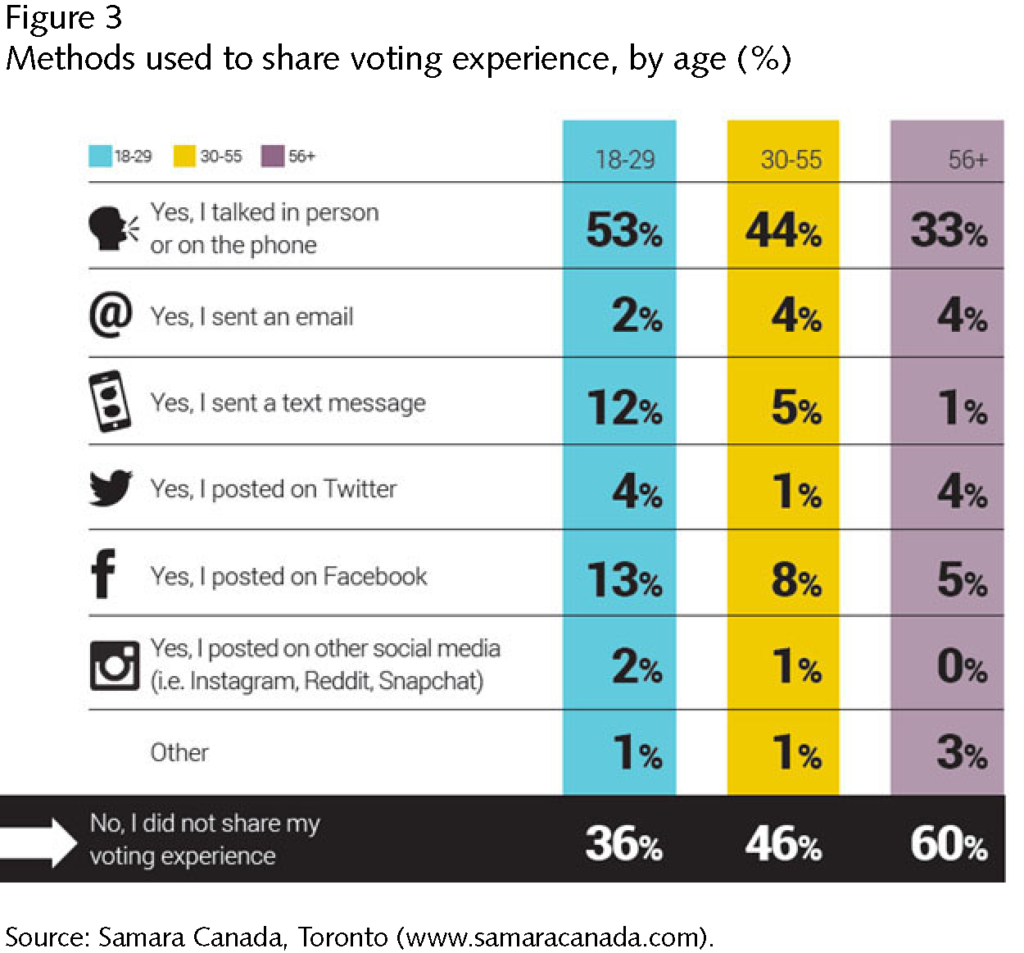

Not only did they discuss politics, the youngest cohort also shared their voting experience at higher rates than older people. Indeed, only 36 percent of young people kept their voting experience to themselves, while 60 percent of the oldest cohort did the same.

In terms of method, 53 percent of young Canadians spoke on the phone or in person about their experience voting, while only 33 percent of Canadians aged 56 or older did. These patterns capture a generational shift in attitude, from voting as a private act of duty to voting as a social, shared experience.

Since we know that social pressure — seeing a trusted friend do something — can have a strong effect on voting, young people themselves encouraged voting in their social group, just through the act of sharing.

“Digital natives” once again defied expectations when it came to sharing: Among 18-to-29-year-olds, the most popular way to communicate their voting experience was in real life (phone or in person), with only 13 percent sharing their voting experience on Facebook and 4 percent sharing on Twitter.

Young Canadians are more interested in sharing their voting experience with others (figure 3). Their stories could have been about who they voted for and why, or just about the fact that they voted. Youth are hyperconnected and avid communicators — both in real life and online — and as such they are effectively positioned to shape the views of their peers and fellow voters. In the 2015 election, Elections Canada found, 67 percent of youth indicated their friends encouraged them to vote, compared with 45 percent of older Canadians. When endorsements, such as that of a newspaper’s editorial board, no longer sway public opinion as they may have once done, parties and candidates must seek out new influencers.

Photo: Chinnapong / Shutterstock.com

This article is part of the Public Policy and Young Canadians special feature.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.