In a recently published Policy Options article “A boost for Armenia and international justice,” Canada was asked to take action on behalf of Armenia in its dispute with neighbouring Azerbaijan over the region of Nagorno-Karabakh, which has an ethnic Armenian majority but is internationally recognized as legally part of Azerbaijan.

Armenia invaded and occupied the region nearly 30 years ago, justifying that action as protecting its ethnic “brothers” there – an argument that is eerily reminiscent of Russia justifying its devastating invasion and atrocities in Ukraine in part as an attempt to protect ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine.

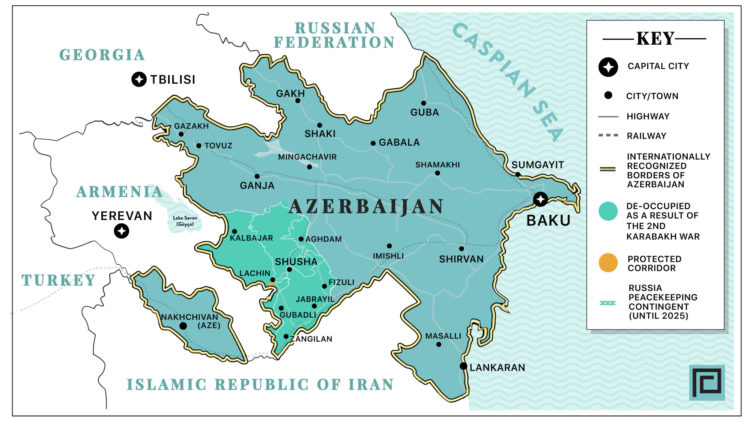

The events described in the Policy Options article are selectively chosen snapshots of the longstanding conflict, with most referring to the period after a brief second war in 2020 that ended with Azerbaijan’s decisive victory and restoration of its territorial integrity.

In the Karabakh crisis, Canada must support rules-based international order

The article does not mention many of the events that led up to that second war and the refusal of Armenia for almost three decades to withdraw from Azerbaijan’s sovereign territory. Armenia’s invasion and occupation was condemned repeatedly by the UN Security Council and many countries.

For example, in a way similar to the Russian occupation of some of Ukraine’s territory and the ensuing refugee crisis there, the occupation of Azerbaijan’s territory in the 1990s saw 700,000 Azerbaijanis ousted from the region, which Azerbaijan calls Karabakh.

In his Policy Options article, Vrouyr Makalian urges the Canadian government to consider a series of actions, including sanctions against senior Azerbaijani government leaders for a number of reasons, such as not ensuring respect for the rights of Armenians in the region in the aftermath of the 2020 war and violating the rights of the Armenian captives still in the custody of Azerbaijan. But these arguments do not add up.

First, Ilham Aliyev, the president of Azerbaijan, has declared on many occasions that the rights of Armenians in his country will be protected – just like all other ethnic groups within a multinational and multi-faith country such as Azerbaijan.

Second, Makalian did not call for similar sanctions against Armenians who committed war crimes during the first war or Armenia’s almost 30-year occupation, including the killing of 613 Azerbaijani citizens in the town of Khojaly in 1992. The former president of Armenia, Serzh Sarkisian, who was defence minister at the time, publicly declared: “Before Khojaly, the Azerbaijanis thought that they were joking with us, they thought that the Armenians were people who could not raise their hand against the civilian population. We needed to put a stop to all that. And that’s what happened.” The Canadian government has officially called this both a “massacre” and a “terrible tragedy.”

Makalian also writes: “UN experts called for the release of all captives in February 2021. The call provoked mixed reactions due to its textbook diplomatic neutrality, by which no distinction was made between the handful of Azerbaijani captives and the hundreds of Armenian captives.”

He does not mention that the real prisoners of war were exchanged already. Those still in Azerbaijani custody are accused of crossing the border into Azerbaijan in December 2020 in defiance of the tripartite agreement that ended the second war in November 2020. It’s also noteworthy that more than 4,000 Azerbaijanis are still missing from the ’90s war, according to official sources, and that Armenia has not disclosed information on their whereabouts as yet.

When it comes to the role of Canada, I beg to differ here, too. The ways that Makalian sees Ottawa intervening in the dispute would have no meaningful impact on bringing about peace in the region and would contradict Canada’s traditional role of being a strong proponent of international law, as well as an honest broker and even-handed player globally.

Today, the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan, as recognized by the United Nations, has been restored and both Azerbaijan and Armenia have declared their commitment to sign agreements to delimit and demarcate their borders as soon as possible. The prospects of economic development and co-operation in the region are immense.

Supporting peace is the only way to stay true to Canadian values. Therefore, Canada must provide support to both Azerbaijan in landmine clearance in the formerly occupied territories and in rebuilding its destroyed cities and villages, and to Armenia in recovering from its difficult economic situation.

Ottawa has taken the first step in this direction by announcing recently it will open an embassy in Armenia. The Canadian government must do the same with respect to Azerbaijan and establish a diplomatic presence in Baku, too. This will ensure that Canada positively contributes to the establishment of long-term peace and development in the region by listening to both Azerbaijan and Armenia.

But most importantly, the federal government must continue to stand firmly in support of the territorial integrity of sovereign countries that have fallen victim to invasion by Russia or other countries.

The attempts by different interest groups to sway Canada’s policies in the direction that would favour one side or the other in any conflict are detrimental to Canada’s global standing. Given the occasional diaspora-influenced politics and favouritism in our country, this is a real risk.