The death notice published on the website’s home page was low-key and matter of fact. “We regretfully announce that NewsKamloops will cease publication today, Sept. 30, 2016. We’ve enjoyed the experiment of publishing an independent, online newspaper owned and written by Kamloops people, and we thank readers who have made us their news source over the past 14 months.”

The demise of another news source attracted little attention during what was already a tough year for local news consumers. Across the country, local broadcast and print newsrooms were hit by cutbacks, consolidations and closures while some digital-first news sites such as NewsKamloops struggled to stay afloat.

During the first months of 2016, PostMedia announced major layoffs and newsroom mergers in Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver. The presses went silent at the daily newspapers in Guelph, Ontario, and Nanaimo, British Columbia. And a study commissioned by Friends of Canadian Broadcasting warned the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission that without intervention, half of Canada’s small- and medium-market television stations could disappear by 2020. Indeed, growing concern about the availability of local news prompted the House of Commons Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage to launch hearings on how broadcast, digital and print media inform people about local and regional experiences.

In a bid to fill in some of the gaps in the data on the media landscape, our investigation into what we call “local news poverty” explores the extent to which local news media are meeting the information needs of people living in rural areas, suburban municipalities and smaller cities and towns outside of Canada’s major media hubs. Local news poverty, we argue, is greatest in communities when residents have limited or no access to timely, verified news about local politics, education, health, economic and other key topics they need to navigate daily life.

Our research consists of a crowd-sourced map that tracks changes to local news outlets across the country and a separate study that examined how news media in eight Canadian communities covered the local race for member of Parliament in the 2015 federal election. The results suggest that local news is at risk and unevenly available across the country.

The underlying premise of our research is that there is reason to be concerned if reporters aren’t covering city council, reporting on the latest police arrests or providing updates on how money raised by the United Way’s annual fundraising drive is being spent. The US-based Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy thinks so too. It concluded that information is “as vital to the healthy functioning of communities as clean air, safe streets, good schools, and public health.” In addition to connecting residents by providing them with a shared set of facts and information, the commission observed that access to information allows people to hold public officials accountable and enables community members to work together to solve common problems.

Scholars have identified different types of “critical information” that citizens need to successfully navigate everyday life, benefit from education and employment opportunities and, if they are so inclined, participate in local democracy. The eight topics on these scholars’ list include emergencies and risks, health, education, transportation, economic opportunities, the environment and civic and political matters.

While angst about the state of local news has only recently pushed its way onto the public agenda in Canada, hand-wringing about what’s going on, why it matters and what to do about it has been underway for some time in other places. A study of Danish newspapers observed that although newspapers are no longer the direct source of news for the majority of citizens, they are the still the main providers of independent, professionally reported news that other local news outlets rely upon for their own local public affairs coverage. In the United States, researchers who compared the local news environment in three New Jersey communities found that “lower-income communities are dramatically underserved relative to wealthier communities” and that they also receive most of their news from fewer sources. Another investigation concluded that civic engagement declined in Seattle and Denver immediately following the closure of local newspapers in those two cities. And a Pew Research Centre report on Local News in the Digital Age found there was little discussion on Twitter about the high-profile local news stories covered by traditional media, and that when news was discussed at all, it tended to deal with national political issues.

Our research contributes a Canadian perspective to this emerging body of scholarship.

The Local News Map

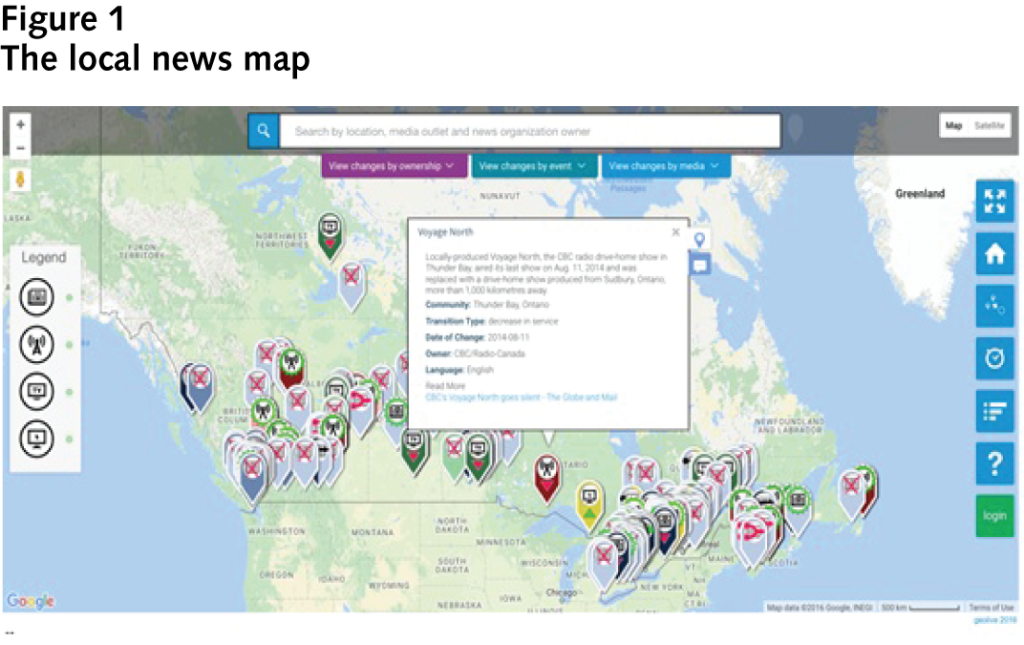

The Local News Map invites contributors to add information about changes — launches, closures, service increases and service reductions — affecting local broadcast, online and print media in Canadian communities (figure 1). To avoid the inclusion of opinion-only blogs, websites that just list local events, and advertising flyers that masquerade as newspapers, we define local news producers as news organizations that first, demonstrate a commitment to accuracy and transparency and, second, focus primarily on the timely reporting and publication of original, verified news about people, places, issues and events in a geographically defined community.

Source: The Local News Research Project.

The map launched on June 14, 2016, on the journalism news website J-Source.ca and became the site’s most viewed item that month. Our objectives in creating this online resource were to spark debate about what’s happening to local journalism, generate data to inform that debate, track changes in local news availability, and help researchers identify patterns and trends in the local news sector. The map offers a big-picture idea of what is happening to local journalism, and it also allows users to zoom in and examine what is going on at the community level. Its filters can be changed to show what is happening to a specific type of news media — community newspapers for instance — and to highlight changes to local news outlets undertaken by different media proprietors.

The map, admittedly, is only as good as the information that users add to it. We do, however, moderate the content for accuracy, so we think the marker information is reliable and that the trends we are seeing reflect reality.

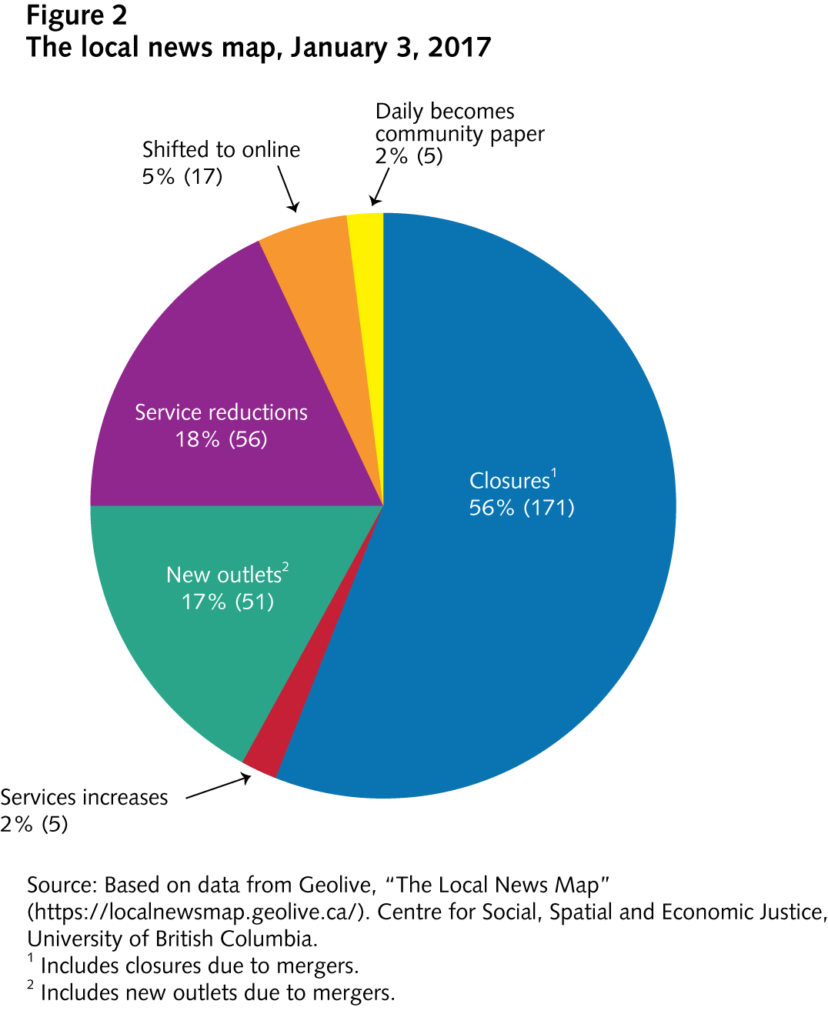

So, what are we seeing? Six months after its launch, the map tells a powerful and disturbing visual story of newsroom closures that far exceed the number of new ventures. When we last examined the data on January 3, 2017, there were 305 markers on the map highlighting changes to local news outlets dating back to 2008. Of those, 171 markers documented the closure of local news outlets in 138 communities. By comparison, only 51 markers highlighted the launch of new local news outlets.

The data also point to other trends, such as

- Major disruptions in the community newspaper (papers published fewer than five times per week) sector. Community papers account of 120 of the 171 news outlet closures.

- A dearth of new digital-first local news sites to replace the loss of community newspapers and other legacy media. To date, only 18 markers indicating new, born-on-the-Web news sites have been added to the map (figure 2).

Local news coverage of the 2015 federal election

In our second research initiative, we set out to measure variations in the availability of local news across the country. To do this, we examined how news media in eight communities covered the local contests for member of Parliament during the 2015 federal election. We focused on coverage of the local races, because the election is a major news event and because news about the contest to represent a community in the House of Commons qualifies as a critical information need. As such, we argue that the amount of coverage devoted to the local races is also a proxy for the overall performance of local media in each community.

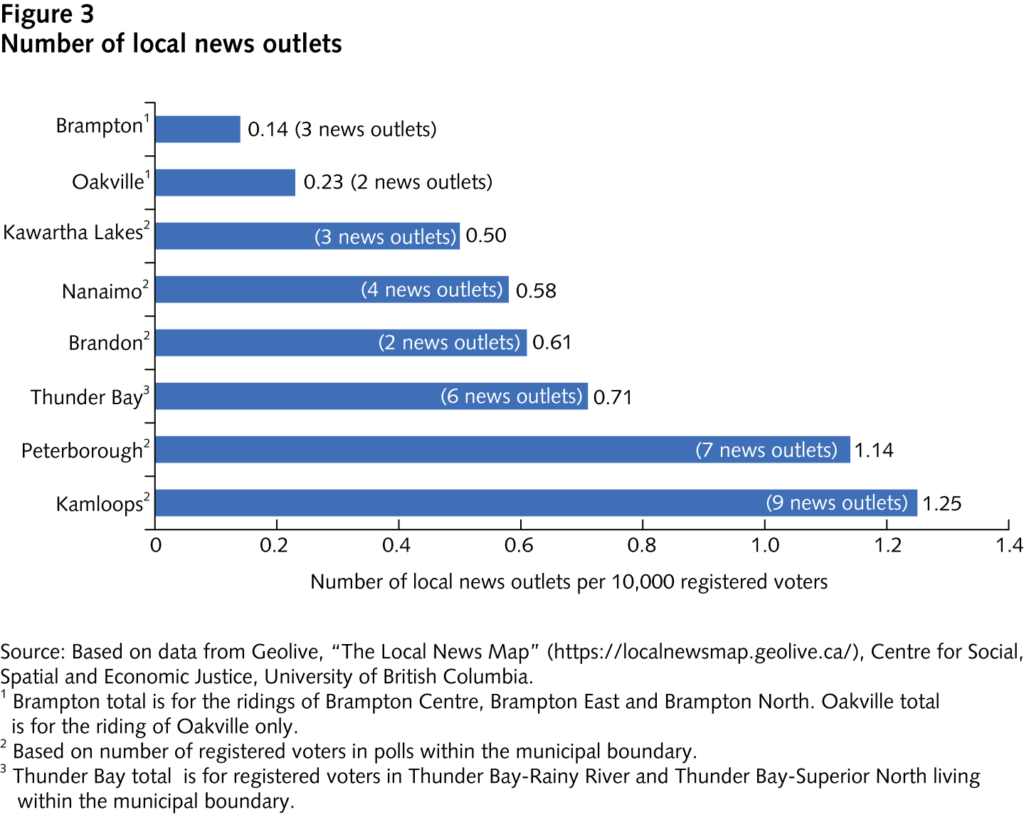

The eight communities were a mix of smaller Canadian cities and rural and suburban municipalities. Our list included ridings in Peterborough, City of Kawartha Lakes, Oakville, Brampton, and Thunder Bay, Ontario; in Brandon, Manitoba; and in Nanaimo and Kamloops, British Columbia (figure 3). After identifying the local news sources available to electors in each community, we collected all of the election-related stories they generated during the month leading up to the vote. We then separated national and local stories, identified the topic of each story, and determined whether the item was produced by the local newsroom or supplied by a wire service.

The results to date point to

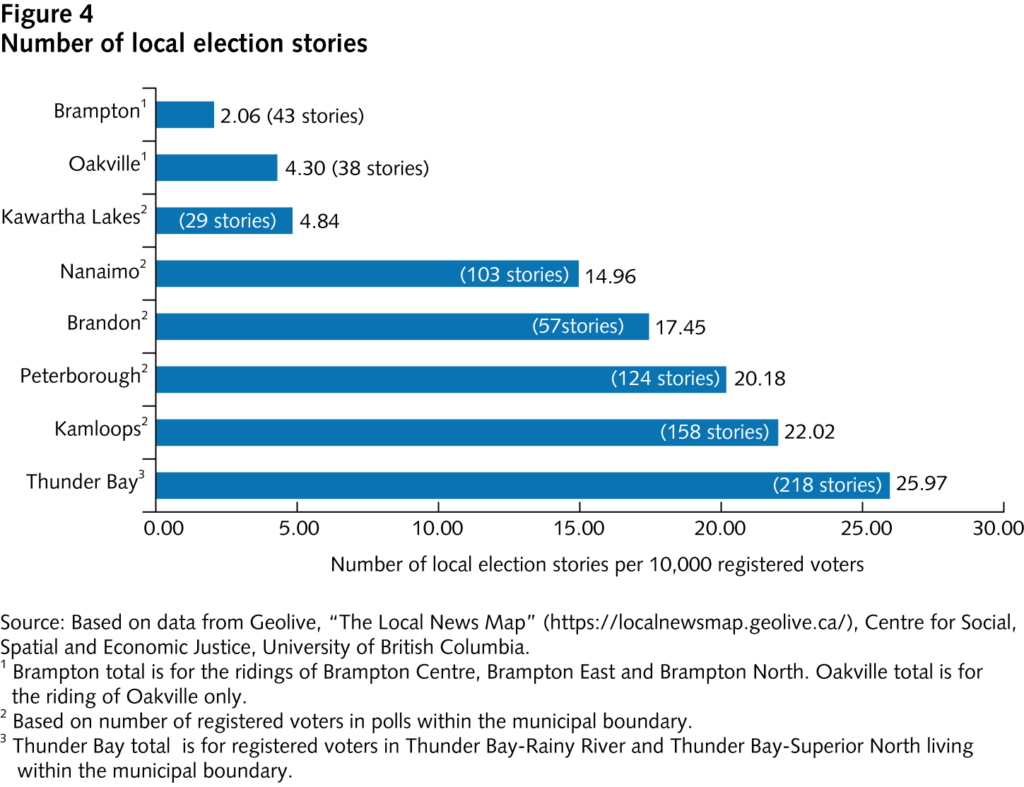

- Significant differences in the number of local news sources in the different communities (figure 4).

- Significant differences in the number of stories about races for Member of Parliament It’s worth noting that since the election, the local news landscape has deteriorated in two communities. The Nanaimo Daily News, which published 57 stories or half of all local coverage of the race to represent Nanaimo, ceased publication on Jan. 29, 2016. In Kamloops, NewsKamloops which published 36 stories or about a quarter of all the local election coverage, ceased publication on September 30, 2016.

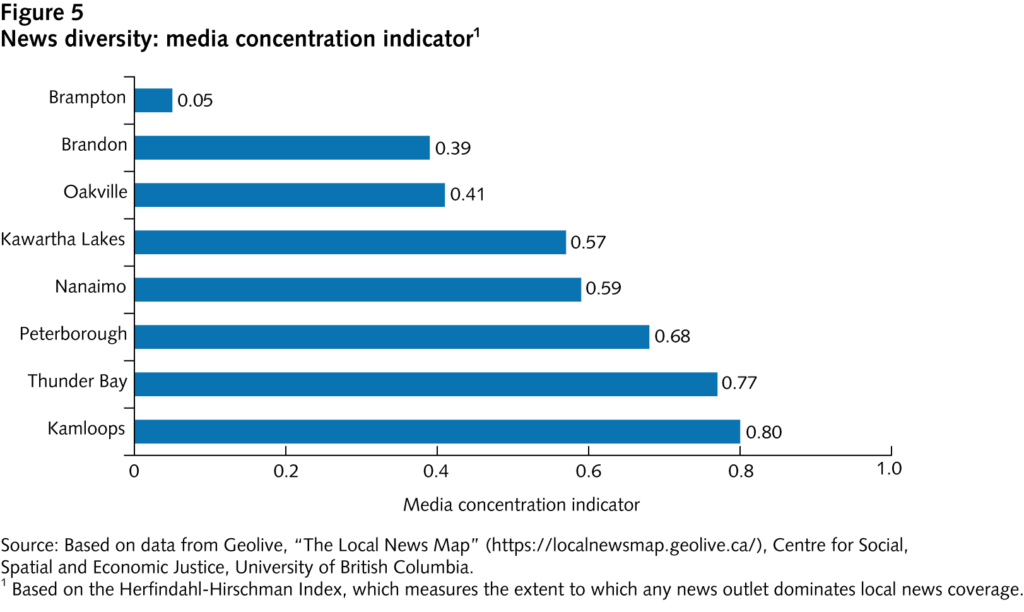

- A significant lack of diversity of news sources in some communities compared to others. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, which we used to measure media concentration, shows that in Brampton, just one local news source dominated the provision of news about the local race for member of Parliament. In Thunder Bay and Kamloops, by comparison, the coverage was spread more evenly among local news outlets (figure 5).

A tale of two cities

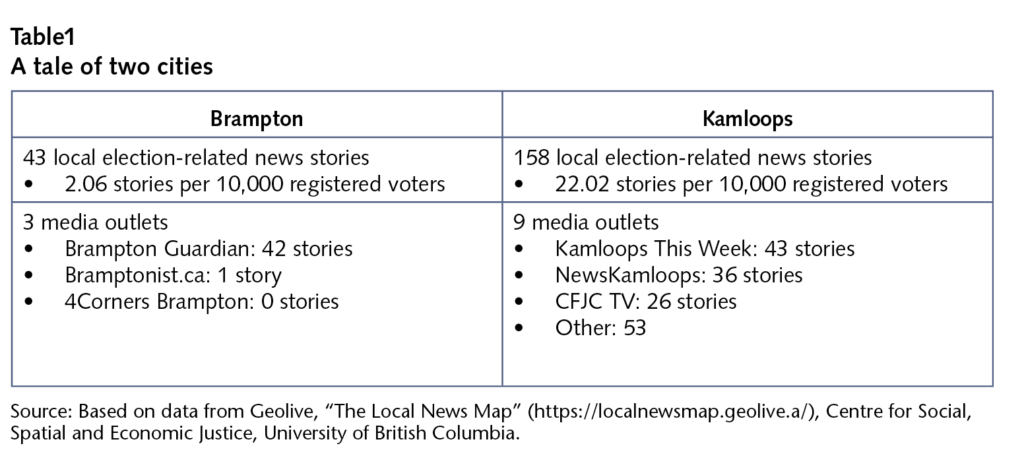

The data illustrate that the coverage of local contests for MP during the 2015 election varied significantly according to where voters lived. By all three measures, registered voters in Kamloops, for instance, enjoyed relative “local news affluence” and coverage was generated by a greater variety of sources than voters in the Brampton ridings we examined (table 1).

What’s next?

Going forward, we hope contributors will continue to add information to the Local News Map so that researchers, the public, journalists and policy-makers can track what’s happening to local news sources across the country.

Our long-term goal is to help with the identification of workable solutions to local news poverty. Plenty of experiments designed to bolster the availability of local news are already underway. For instance,

- In the Skeena area of northern BC, where the population is deeply divided over the proposed Aurora LNG export terminal, Vancouver-based Discourse Media is exploring the idea of training and mentoring citizen journalists and holding public consultations to find out what types of stories are required to advance the discussion

- In the UK, beginning this year (2017), the BBC will pay for 150 journalists, who will be hired by local news organizations to cover local politics and public services. The stories will be published by the local news partner and shared with other participating local media and the BBC.

- In the United States, the foundation-funded Local News Lab is supporting experiments designed to foster more informed communities in the state of New Jersey. Rather than fund the creation of news content, the lab is working to build local capacity in various ways, including testing new business strategies in partnership with newsrooms, foundations and universities. The lab also recently issued a list of lessons learned from its various attempts to improve local news availability.

On of the lessons from the lab is that hiring the right advertising sales person is one of the “thorniest and persistent challenges” for web-based startups. It’s a lesson Claude Richmond, who launched NewsKamloops after the closure of the local daily newspaper, learned the hard way. As he said in an interview for this article, “I’ve always been a news junkie,” the former BC cabinet minister says. “The paper had been closed for over a year before I got the idea (for NewsKamloops). I took a look at what was going on and thought there was room for a better online news site. I thought we could do a better job.”

Richmond says his inability to find personnel to sell online advertising killed the site: “I would have thought it would be one of the easiest tasks, but it turned out to be the one that took us out.”

As the variety of initiatives outlined above suggest, there is no silver bullet for communities with compromised local news environments. The next step in our research, therefore, will be to investigate whether certain solutions are more suited to some places than others. To improve our understanding of why some communities are poorly served by their local media, we are creating an index to rank the eight election-study communities according to their relative levels of local news poverty. We will then try to identify the key characteristics of the places that are news “poor” and those that are relatively news “affluent.”

We won’t be starting from scratch: Existing research suggests that income, proximity to a major media hub and the presence of a local CBC/Radio-Canada newsroom are factors that might distinguish communities that suffer from local news poverty from others that are better served. Other potential determinants of local news affluence/poverty that we will explore include media ownership, population size, educational attainment, diversity, the presence of a university, and the existence of a local daily newspaper.

If we succeed in creating a diagnostic “checklist” of characteristics that can be used to pinpoint places at risk of local news poverty, our hope is that it will then be easier to identify tailor-made remedies. We expect there will be some characteristics common to all communities where local news poverty is a problem. We suspect, however, that the underlying factors responsible for an anemic local news environment will vary from place to place, depending on local conditions. When it comes to solutions, in other words, one size will not fit all.

The news poverty project has received support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC); the SSHRC-funded Canadian Geospatial and Open Data Research Partnership; the Canadian Media Guild/CWA Canada; Canadian Journalists for Free Expression; the federal Mitacs Accelerate Program; Unifor; and Ryerson University. It has has benefited from the hard work and enthusiasm of research assistants Brock Campbell, Holly Clermont, Avneet Dhillon, Isabelle Docto, Eliana Macdonald, Brigitte Petersen and David Rudin. Our many thanks also to geoweb programmer Nick Blackwell at the University of British Columbia; Ryerson Journalism Research Centre coordinator Allison Ridgway; and Christina Wong, data manager for the Local News Research Project.

This article is part of the special feature The Future of Canadian Journalism.

Photo: A view down 3rd Avenue in downtown Kamloops, British Columbia. The Canadian Press Images/Don Denton

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.