In pushing health care reform, President Barack Obama is confronted by contemporary critics and haunted by history. Obama has to learn from the last Democratic president’s failure. Bill Clinton also championed health care reform. Moreover, Obama cannot forget that Americans are ambivalent about big government, not only since the Ronald Reagan era but since the American Revolution.

Americans are torn. Most retain enough of their nation’s historic fear of executive power to dislike big government in the abstract. But after 75 years of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Harry Truman’s Fair Deal, of John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, Americans are addicted to many of the government programs that together make their government big, their tax bills high, their bureaucracy dense — as well as their society a kinder, gentler place to live. Usually, Democrats miscalculate by overlooking this traditional fear of big government; Republicans err by overstepping and eliminating essential programs that Americans now take for granted.

Although the American Revolution was far less radical than the French and Russian revolutions, Americans did rebel against executive power. The revolutionaries’ experience with the King of England — and his governors in the colonies — soured a generation on strong, centralized government. The younger men of the revolution such as Alexander Hamilton, who assisted George Washington in trying to win the war, better understood the need for an effective government. They pushed for the new constitution in 1787, replacing the Articles of Confederation that bore the mark of the revolutionary struggle by keeping the national government weaker than the states, and the executive impotent compared to the Congress.

Still, the Constitution established a federal government that was not supposed to overwhelm either “We the People” or “these United States,” as the country was called at the time. Moreover, there was a strong ethos of self-sufficiency. People were supposed to take care of themselves, especially considering America’s riches.

This question of how vigorous the new federal government should be split George Washington’s cabinet. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, having opposed executive power so eloquently in the Declaration of Independence, fresh from admiring the French Revolution up close, led the charge with his friend James Madison against a strong government — and executive. When Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton proposed a national bank in 1791, Jefferson opposed this power grab by subtly misquoting the Constitution. Analyzing what he called the Constitution’s “foundation,” Jefferson wrote to Washington that the 10th Amendment of the Constitution declared that “all powers not delegated to the United States, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States or to the people.” Jefferson feared that taking “a single step” beyond Congress’s clearly drawn boundaries meant seizing “a boundless field of power,” with no limits. In fact, the Constitution reads “the” powers, not “all” powers. The original text still preserves the prerogatives of the state and the people, but less globally.

Pushing back, Hamilton hastily drafted his opinion defending the Bank of the United States as constitutional. Hamilton endorsed a “liberal” reading of what is known as the “elastic clause,” article I, section 8, authorizing the new Congress “to make all laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution” the powers granted to the federal government. Appreciating the clause’s “peculiar comprehensiveness” regarding the government’s many implied powers, Hamilton said that Jefferson’s strict reading made the clause unduly “restrictive,” an “idea never before entertained.” Hamilton said it would be as if the Constitution only authorized laws that were “absolutely” or “indispensably” “necessary and proper.”

This Hamilton-Jefferson divide defined the debate for more than a century. Jeffersonian liberals wanted small, non-intrusive government, thinking of farmers as ideal citizens, and trusting self-sufficiency over any kind of government patronage. Hamiltonian conservatives wanted a larger and more vigorous government to help America develop, trusting private-public partnerships to serve the economy and the citizenry.

While saving the union in the 1860s, President Abraham Lincoln articulated a vision of the nation, united, effective and supreme, forever changing the power balance between the federal government and the states. After the Civil War, these United States became the United States. Moreover, the often forgotten part of Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party agenda advocated a more activist approach to helping farmers and labourers, using national power to improve individuals’ quality of life.

With the growth of government — and corporations — during the Civil War, with the rise of a national currency (the greenback), a national debt and national income taxes, American business leaders noticed that government involvement could restrict their growth as much as feed it. In what the political scientist Clinton Rossiter called “the Great Intellectual Train Robbery of American History,” conservative business leaders hijacked Jeffersonian small-government liberalism to suit their own purposes. The “laissez-faire” doctrine they embraced suggested that government should step back and let corporations thrive. Connected to this hands-off policy was a notion that the poor could fend for themselves — or be taken care of locally, by relatives, churches, volunteers.

After 75 years of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Harry Truman’s Fair Deal, of John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, Americans are addicted to many of the government programs that together make their government big, their tax bills high, their bureaucracy dense — as well as their society a kinder, gentler place to live.

As the nation grew, so did the government, and so did the sense of collective responsibility. Both the rural-based Populist movement of the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s and the more urban-based Progressive movement that began in the 1890s and lasted through the 1920s mobilized the government to protect the people against corporate fat cats and the vicissitudes of life. Still, the Great Depression of the 1930s initially highlighted the limits of Progressivism — and the continuing American allergy to dramatic government intervention. Thomas Jefferson’s ideas survived, propped up by private-property-protecting business interests that rejected government redistribution or regulation as anti-American.

The despair spreading through society, combined with the hopes generated by radicals in Europe and Soviet Russia, challenged American stability and values. While only a few actually waved the banner of revolution, many feared that the American economic system was broken, and the sclerotic American political system made it unfixable.

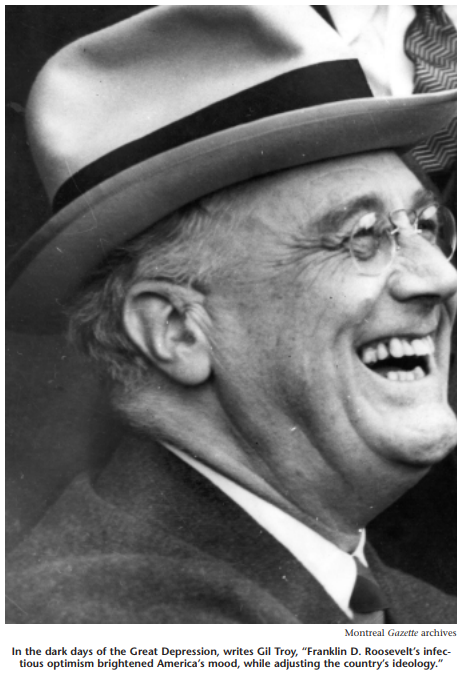

In these dark days, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s infectious optimism brightened America’s mood, while adjusting the country’s ideology. Roosevelt’s “First Hundred Days” in office set a template of presidential action and established numerous precedents for direct government intervention in American life. Mixing Jefferson’s democratic populism with Hamilton’s top-down centralization, Roosevelt created big-government liberalism. “I am not for a return to the definition of liberty under which for many years a free people were gradually regimented into the service” of capitalism, Roosevelt said. Liberalism “is plain English for a changed concept of the duty and responsibility of government toward economic life.”

Using appeals to the collective, justifying his emergency actions with military analogies, Roosevelt offered a three-pronged program. First, he mobilized the power of government to offer immediate relief, shifting the responsibility from churches, community groups and relatives to the local, state and federal governments. Then, he tried to jump-start a recovery, putting the government in the business of micromanaging the economy — and violating the long-standing American aversion to federal budget deficits. Finally, he sought broader reforms to institutionalize the changes and avoid a repeat.

Suddenly, the executive branch was choreographing currency shifts, bringing electricity to the South, eliminating corporate abuses, subsidizing individual homeowners. The government provided the old with pensions, the disabled with support and the poor with sustenance while hiring millions through a new “alphabet soup” of agencies, the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), the PWA (Public Works Administration), the AAA (Agricultural Adjustment Administration) and the NRA (National Recovery Administration). The “first duty of government is to protect the economic welfare of all the people in all sections and in all groups,” Roosevelt said in a 1938 fireside chat. This casual statement reflected a revolutionary departure from Alexander Hamilton’s vision, even more so from Thomas Jefferson’s.

The Social Security Act of 1935 was arguably the single most dramatic New Deal reform. The Act helped the elderly poor immediately and began a federal pension plan gradually. It eventually offered unemployment insurance, federal aid to dependent mothers and children, and assistance to the blind and handicapped. Half a century of Progressive agitation culminated in this legislation. Roosevelt made this great leap seem like a logical next step. His genius for making revolutionary changes appear inevitable built popular support for these audacious steps. The Democratic Party became America’s party, the party of activist government protecting the middle class and the poor.

Roosevelt wanted to provide “cradle to grave” security, but constructing a workable plan took years. Advisers and activists debated whether there should be cash grants or welfare programs, whether support should be national or state-based, whether social welfare guaranteed dignity or destroyed individual responsibility. Such comprehensive social insurance deviated from American constitutional practice and offended many conservatives, both rich and poor. The National Association of Manufacturers blasted this attempt at “ultimate socialistic control of life and industry.”

To soften the blow, Roosevelt injected an all-American centrist twist into this legislative master stroke. Workers would pay into the Social Security system for decades before getting their payouts. This innovation reinforced the sanctity of private property, individual dignity and government centrality. “We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral and political right to collect their pensions and their unemployment benefits,” Roosevelt explained. The individual contributions also guaranteed the program’s future. “With those taxes in there,” Roosevelt declared, “no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program.”

Roosevelt created big-government liberalism. “I am not for a return to the definition of liberty under which for many years a free people were gradually regimented into the service” of capitalism, Roosevelt said. Liberalism “is plain English for a changed concept of the duty and responsibility of government toward economic life.”

After vigorous debate, most members of Congress could not oppose helping the American community’s weakest, sickest and oldest members. The House passed the bill 371 to 33. The Senate bill passed two months later, in June 1935, 76 to 6. Roosevelt’s Social Security Act truly was a bipartisan bill enjoying overwhelming support.

Roosevelt’s “New Deal” did not end the Great Depression. But it reassured Americans. It repositioned the government and the president in the centre of American political, economic, and cultural life. The advent of The Second World War jump-started the economy — and launched a half-century of unprecedented economic prosperity. America became the world’s first mass middle-class society. The war also brought about a level of government intervention, regulation and, of course, taxation that would have been denounced as “Bolshevik” by millions at the start of Roosevelt’s reign. But step by step, improvisation by improvisation, speech by speech and crisis by crisis, Roosevelt had brought Americans to a new approach — and understanding. Europeans and Canadians remained surprised by America’s limited welfare state; thoughtful Americans with some sense of history were surprised at how far this initially reluctant giant had moved toward government activism.

Still, for all his talk of “cradle to grave” coverage, FDR could not get any bill for universal health care out of committee. Harry Truman’s Fair Deal expanded Roosevelt’s program, but Truman was no more successful in getting a health care bill to the floor of the Congress. In the 1950s, by maintaining signature New Deal programs such as Social Security, the first Republican president since the New Deal, Dwight Eisenhower, ratified Roosevelt’s vision and guaranteed that America would maintain a generous welfare state. Eisenhower also averted a bruising partisan battle.

The federal government’s meteoric growth and the equally quick emergence of a national focus meant that the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s could function — and succeed — as a national movement fighting an injustice rooted most intensely in one region, the South. The civil rights movement’s success in an age of big government and national television furthered the development of a national conversation about oncelocal problems — and the search for national solutions. John Kennedy’s tragically brief presidency raised expectations further.

Increasingly, the debate during Kennedy’s years was no longer “should the federal government be involved,” but “how should the federal government solve particular problems.” What was so revolutionary about this shift was that it no longer seemed remarkable. Government had become so big, so centralized and so central in Americans’ lives, many forgot how novel a phenomenon the welfare state was in American history. It would take conservatives who began mobilizing in the 1960s around Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan nearly 20 years to remind Americans that questioning big government was not marginal or anti-American, but rooted in some of the most fundamental American political traditions and assumptions. Increasingly, it seemed that Americans liked their government small in the abstract, but big when it came to helping them.

Lyndon Johnson became president in 1963 after John Kennedy’s assassination, trusting in a governmental solution for nearly every problem. “The roots of hate are poverty and disease and illiteracy, and they are broad in the land,” Johnson proclaimed in an early speech, planning to legislate these scourges into oblivion. Johnson linked the challenges of Communism, civil rights and poverty. He wanted to win the Cold War by perfecting America, vindicating democracy worldwide.

In May 1964, Johnson redefined America’s historic mission at the University of Michigan’s commencement ceremonies. After settling the land, Americans had developed an industrialized infrastructure. During this next stage Americans would go beyond mere riches and power, “to enrich and elevate our national life, and to advance the quality of our American civilization.” Johnson envisioned a “Great Society,” providing “abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice…The ”˜Great Society’ is a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and to enlarge his talents…It is a place where the city of man serves not only the needs of the body and the demands of commerce but the desire for beauty and the hunger for community.”

Propelled by his electoral landslide in November 1964, Lyndon Johnson surpassed the New Deal. In 1964 and 1965, Johnson muscled through an ambitious array of laws that transformed the way the government helped the poor, the sick, the old, the young. Eventually, staffers counted 207 laws as “landmark” legislative achievements. Under Johnson, the federal budget first topped $100 billion. Aid to the poor nearly doubled, health programs tripled, and education programs quadrupled. LBJ outdid FDR by enacting the 1965 Medicare amendment to FDR’s Social Security Act. Harry and Bess Truman received the first two Medicare cards. Medicare was for all older Americans (and some disabled citizens), theoretically paid for by their own contributions when they worked; another program, Medicaid, was a means-tested program for the poorest Americans, and involved state participation as well.

Alas, Johnson could not legislate away America’s problems. Even as Congress passed a landmark civil rights law, the Voting Rights Act, riots erupted in Watts, the Los Angeles ghetto. The Vietnam War became Johnson’s albatross — and America’s burden, wasting billions of dollars, sacrificing 58,000 American lives and bleeding away America’s credibility and confidence. Johnson’s Great Society hopes sank in the Vietnam morass. Johnson retired prematurely, refusing to run for re-election in 1968.

The Great Society’s failure spurred the Reagan Revolution — a backlash against big government. Ronald Reagan spoke eloquently about up-by-the-bootstraps, do-ityourself American individualism, saying the Great Society failed because big government never worked. When Bill Clinton was elected in 1992, he understood his mission as trying to restore Americans’ faith in government, by showing that government could be effective without getting too big.

The Great Society’s failure spurred the Reagan Revolution — a backlash against big government. Ronald Reagan spoke eloquently about up-from-the-bootstraps, do-it-yourself American individualism, saying the Great Society failed because big government never worked.

Ultimately, Clinton failed to enact health care reform because he missed the centre; he forgot how deeply skeptical Americans remained about big government. Few remember how likely prospects for change appeared in 1993. “America’s ready for health care reform and so are we,” South Carolina’s Republican governor, Carroll Campbell, declared, as Republicans scrambled to offer their own alternatives.

Clinton — and his polarizing wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton — squandered that early mix of bipartisan good will and political fear so necessary for an ambitious reform effort in a divided Congress. In what was widely perceived as a payoff for her wifely loyalty amid all the adultery rumours in the 1992 campaign, the First Lady chaired this ambitious health-reform effort.

Rather than developing a general plan with Congress, Mrs. Clinton presented a fait accompli, a byzantine 1,354-page program more suited to the big-government ambitions of Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson than to the small-government era Ronald Reagan had pioneered.

Rather than adjusting the elaborate plan to mollify Republicans, the President and his wife went rigid and attacked their critics. Hillary Clinton refused to compromise. She urged her husband to wave a pen in his 1994 State of the Union address, promising to veto “legislation that does not guarantee every American private health insurance that can never be taken away.” On the stump, the First Lady bashed doctors, pharmaceutical companies, insurance executives and conservatives. Mrs. Clinton mocked those who “drive down highways paid for by government funds” and “love the Defense Department” but object “when it comes to…trying to be a compassionate and caring nation.” The Clintons’ personal scandals, congressional counter-attacks and media nitpicking gradually undermined the effort. Emboldened, Republicans began following the ideologues rather than the moderates. “There has been almost total surrender amidst the largest power grab in U.S. history,” former education secretary William Bennett first complained in October 1993. On Meet the Press, the Republican congressional leader Newt Gingrich denounced the plan as “the most destructively big-government plan ever proposed.”

As the Clintons lost control of the health care debate, two powerful streams in modern American ideology merged. Cartoons of the “Evil Queen” offering up a Pandora’s box of “socialized medicine” linked ancient and modern obsessions about government power and powerful women. Partisan Republicans and cynical reporters described an out-of-control, crusading radical feminist and her henpecked, secretly liberal husband imposing another arrogant, expensive Great Society failure on the American people. “National Health Care: The compassion of the IRS! the efficiency of the post office! all at Pentagon Prices!” one bumper sticker seen in 1994 proclaimed. This crude caricature encapsulated many of the antigovernment themes developed in the 1980s and demonstrated the Clinton opponents’ success in transforming the public debate.

Most dramatically, the health insurance industry created a fictional couple to balance out the presidential couple. In a $14-million advertising campaign, compounded by all the free media coverage it generated, the American people met Harry and Louise, two middle-class Americans struggling with their bills, celebrating Thanksgiving, going to the office — all the while debating health care reform. In one commercial, the announcer warned: “Things are going to change, and not all for the better. The government may force us to pick from a few health care plans designed by government bureaucrats.” “They choose,” Harry then says, and his wife chimes in, “We lose.” In another, Louise tells Harry: “There’s gotta be a better way.” Furious — and reflecting just how effectively the Harry and Louise message had penetrated, Mrs. Clinton snapped in November that the insurance companies “have the gall to run TV ads that there is a better way, the very industry that has brought us to the brink of bankruptcy because of the way that they have financed health care.” Speaking of Harry and Louise, Ben Goddard, the president of the agency that invented them, exulted: “These are people” average Americans “feel comfortable with; they might invite them to a Christmas party.” Liberals and Democrats tried to mobilize, but no reply was as effective as the Harry and Louise onslaught.

The Clintons’ operatic marital dynamics kept the President wed to Hillary Clinton’s rigid strategy even as their initiative fizzled. The Clintons further alienated Congress by bypassing the usual procedures and slipping this major reform into a budget bill. President Clinton did not throw himself into the fight as intensely or as nimbly as he had with the budget or the North American Free Trade Agreement. The bill withered on the congressional committee vine; neither the Senate nor the House even voted on it. Bill Clinton’s failure to deliver even a compromised health care bill symbolized a broader failure to fight effectively for policies and principles with the same tenacity and agility he would display in 1998 when fighting for survival during the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

Barack Obama’s people have studied the Clinton case carefully — many, including White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel, witnessed the failure from within the Clinton administration. Obama’s decision to let Congress draft the health bill, for example, reflects an attempt to avoid the dynamics that hurt the Clintons whereby the White House sent legislation down Pennsylvania Avenue to Capitol Hill for approval. But the real test is yet to come. Can Obama convince Americans that universal health care coverage should be as American as Social Security (if not apple pie)? Or will the Republicans play to Americans’ traditional suspicion that big government will do more harm than good?

Photo: Shutterstock