The members of Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission (ecofiscal.ca) are Chris Ragan (Chair), McGill University; Elizabeth Beale, Atlantic Provinces Economic Council; Paul Boothe, Western University; Mel Cappe, University of Toronto; Bev Dahlby, University of Calgary; Don Drummond, Queen’s University; Stewart Elgie, University of Ottawa; Glen Hodgson, Conference Board of Canada; Paul Lanoie, HEC Montréal; Richard Lipsey, Simon Fraser University; Nancy Olewiler, Simon Fraser University; and France St-Hilaire, Institute for Research on Public Policy. This article is adapted from section 4 of Smart, Practical, Possible: Canadian Options for Greater Economic and Environmental Prosperity (https://ecofiscal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Ecofiscal-Report-November-2014.pdf).

Measurement is crucial for policy-makers: it helps identify gaps, as well as the best policies to address them. In this article we benchmark Canada’s performance against those of a group of comparable jurisdictions: some countries from the G7 (Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States), plus two other small, resource-rich advanced economies (Australia and Norway). First, we assess the extent to which Canadian governments have implemented ecofiscal policies. Second, we benchmark Canada’s economic performance. Finally, we benchmark Canada’s environmental performance.

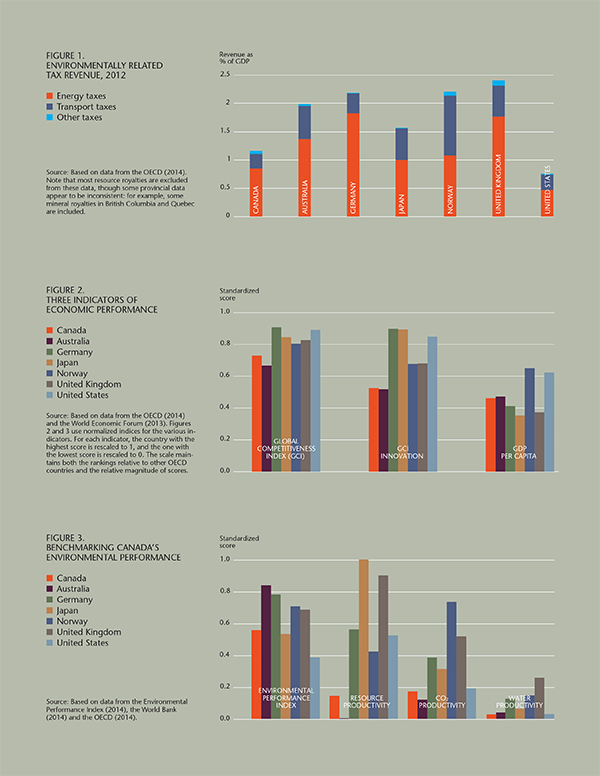

Canada makes limited use of ecofiscal policies. To what extent does Canada use ecofiscal policies relative to other jurisdictions? Figure 1 shows OECD estimates of the revenues generated by “environmentally related taxes” as a share of GDP. (Note that the OECD’s definition includes taxes on any activity directly related to pollution.) Canada is second lowest in the group, suggesting that it is behind the curve in shifting to policies that can more closely align its economic and environmental objectives.

The three categories of taxes that relate to the environment shown in figure 1 are energy taxes, transport taxes and other taxes. Energy taxes include those that apply to energy products and CO2 emissions associated with the consumption of fossil fuels. Transport taxes relate to the ownership and use of motor vehicles. Other taxes include pollution and resource taxes, such as waste charges. In all the countries shown, most of the environmental tax revenue is generated from energy and transport taxes. While the OECD’s definition does not align perfectly with this discussion of ecofiscal policies, it provides a useful metric to assess Canada’s relative use of policies that price pollution and environmental damage.

In Canada, the highest revenues come from the federal and provincial fuel taxes and provincial motor vehicle license fees. These are not designed to achieve environmental objectives, but indirectly they all create incentives to reduce energy use and thus they generate environmental benefits. Canadian taxes also include some that are designed with explicit environmental objectives; British Columbia’s carbon tax is the most significant in terms of revenue. Canada’s other pollution and resource taxes are marginal in scale or in coverage.

Total Canadian government revenues now represent over one-third of our GDP, yet our ecofiscal revenues are just above 1 percent of GDP. Eco-fiscal reform thus presents a tremendous untapped opportunity. Canada could raise an additional 1 to 1.5 percent of GDP through ecofiscal policies if it adopted rates comparable to those in the United Kingdom, Norway and Germany. And according to the International Monetary Fund, Canada could raise additional revenue equal to 1.4 percent of GDP, or about $26.5 billion, with energy taxes that reflect the marginal damage caused by fossil fuel consumption and traffic congestion. Indeed, taxes on various kinds of pollution could be increased, or created where they do not yet exist; at the same time, other distortionary and growth-retarding taxes could be reduced. No change in overall government revenues would be necessary for this type of ecofiscal reform.

Canada can improve its economic- performance. Comparing countries’ economic performances is challenging; each country has unique characteristics and its own strengths and weaknesses. A few key indicators are nonetheless suggestive. Figure 2 benchmarks Canada in terms of three complementary economic indicators:

- GDP per capita is a comprehensive measure of average income within an economy and is the most widely accepted measure of its residents’ material living standards.

- The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) considers important drivers of productivity such as the quality of institutions, infrastructure, education and other market factors.

- The Innovation Index is a subindex within the broader GCI that focuses specifically on innovation, including private investment in research and development, patent applications and university-industry collaboration.

Canada’s limitations in terms of innovation, which have contributed to anemic productivity growth in recent decades, are well documented. In a 2013 report the World Economic Forum notes that “Canada’s competitiveness would be further enhanced by improvements in its innovation ecosystem,” such as increased spending by businesses in research and development and by government in technological products. Countries ranking higher in terms of overall competitiveness systematically rank higher in the innovation component. Top-ranking countries for competitiveness such as Germany and the United States rank significantly higher than Canada in innovation.

Canada’s relatively poor innovation performance is consistent with its low growth in labour productivity. Stronger labour productivity means producing more goods and services with fewer hours of work—so innovation is naturally a key long-run driver of productivity growth. Canadian labour productivity since 2000 has grown at roughly half the annual rate compared with the preceding three decades. In addition, Canada’s performance pales in comparison with that of our most important trading partner: productivity growth in the overall US economy has been about three times the Canadian rate since 2000. If we consider only the business sector, Canadian labour productivity growth has been consistently lower than in the United States since 2008 and has even declined in some years.

This productivity gap and poor innovation record could jeopardize Canada’s relatively strong current performance in terms of GDP per capita. It is often said that the prominence of Canada’s resource sector accounts for the country’s long-standing weakness in innovation, and that our continued emphasis on resource development inevitably confines us to this path. Yet the data in figure 2 suggest this is not the case. Norway is also a resource-intensive economy and scores 29 percent higher than Canada on the GCI’s Innovation Index. Resource development and innovation are not incompatible.

Improved productivity is ultimately the path to higher long-run material living standards, and better management of natural resources is part of the story. Properly valuing our natural resources through smart policies will allow Canadians to reap the maximum benefits of our natural resources. Innovation and efficient resource use will improve Canada’s productivity and competitive position.

Canada can better manage its natural assets. To what extent can Canada improve its management of natural assets? As with measures of economic performance, unique circumstances of each country make comparing environmental performance challenging. Yet benchmarking Canada against other countries can help identify gaps in Canadian performance.

Figure 3 compares Canada with the same set of countries, using four different aspects of environmental performance:

- The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) is a biennial index covering a wide range of national-level environmental data developed by Yale and Columbia universities in collaboration with the World Economic Forum. The 2014 framework combines 20 indicators focused on the protection of human health from environmental damage, ecosystem protection and resource management. Performance is based on the extent to which various policy targets are being achieved.

- Resource productivity is an index of GDP per unit of nonenergy materials used. This indicator is Europe’s headline indicator for its Resource Efficiency Roadmap.

- CO2 productivity is an index of GDP per unit of CO2 emitted. It reflects the extent to which a country generates economic growth without producing carbon dioxide emissions.

- Water productivity is an index of GDP per cubic metre of fresh water used. It shows how efficiently water is used within a country’s economy.

While these metrics do not represent a comprehensive analysis of all dimensions of environmental sustainability, they provide a useful window into Canada’s performance as well as its ability to generate income while minimizing resource depletion. Among its peers, Canada ranks third worst on the Environmental Performance Index. While Canada scores very highly in terms of achieving its targets for protecting human health from environmental damage, it has low scores in terms of ecosystem protection and resource management. Based on the EPI’s indicators, the most pressing issues for Canada are its loss of forest cover, its failures to achieve policy targets for fish stocks and habitat conservation, and its failure to de-intensify carbon emissions from economic growth.

The three productivity indices in figure 3 reinforce Canada’s ranking under the EPI. Our average per capita income is admittedly enviable, but we lag far behind our peers in terms of how we choose to produce that income. Each unit of Canadian GDP depletes more natural assets, uses more material inputs and generates more harmful greenhouse gas emissions than is the case in our comparator countries. The World Energy Council’s 2013 assessment of 129 countries is further evidence of Canada’s poor performance in terms of environmental sustainability. While Canada scores well for measures of energy security and energy equity, it ranks 60th for environmental sustainability. There is an opportunity here to do much better.

Of course, part of Canada’s environmental performance is due to structural factors and national circumstance. Major Canadian sectors such as mining, and oil and gas development are typically more polluting and resource intensive than many others. Similarly, Canada’s relatively abundant freshwater resources have led to weaker incentives to improve water productivity.

Yet Canada’s long-held comparative advantage in the production of natural resources makes ecofiscal reform more important, not less. While it is likely that Canada will always be more resource intensive than Japan or Germany, for example, ecofiscal policy can help us make better use of our valuable resources. As pressure on our fresh water mounts from greater development and ongoing climate change, and international political pressure grows to constrain greenhouse gas emissions, Canada’s environmental performance will have even closer connections to its long-run economic performance. Getting prices and incentives right is critical if we are to continue benefiting economically from our natural wealth while also easing the transition to new and cleaner technologies over time.

Australia—another highly developed, resource-intensive economy—is often compared with Canada in discussions of economics and the environment. Australia scores much higher on the EPI, having achieved more policy goals for issues related to ecosystem vitality. For example, the index suggests that Australia has better managed its forest cover and habitat conservation. However, like Canada, Australia faces challenges with respect to more aggressively reducing its carbon intensity and better protecting its fish stocks. Australia’s low scores on environmental productivity indicators highlight room for improvement in creating economic growth that is decoupled from environmental damage.

Norway also ranks higher than Canada on the EPI, though it too faces challenges related to forest cover and poor management of its fisheries. However, Norway’s performance on environmental productivity indicators suggests that it is possible for resource-rich countries to generate strong economic growth with lower environmental damage and depletion of natural assets. Is it a coincidence that Norway’s strong performance in both environmental and economic terms aligns with its relatively greater reliance on ecofiscal policies?

Canada can do better. This article sheds light on the opportunity for Canada to improve its economic and its environmental performance. Canada’s fiscal structures can be powerful tools for aligning our economic and environmental goals and improving the outcomes, if we choose to design them appropriately.

The aim of ecofiscal policies is to harness the power of markets to provide a cost-effective approach for reducing pollution and environmental damage. By attaching prices to pollution of various kinds, these programs would not only generate incentives to reduce pollution and adopt cleaner technologies, but they would also generate revenues that can be used to drive further economic benefits. Options include reducing growth-retarding taxes, investing in cleaner technology, lessening the burden on vulnerable families and investing in critical infrastructure. The various governments, which face different challenges, are likely to choose different combinations of these options.

The guiding principle behind ecofiscal reform is simple, but the design details matter a great deal. To be successful, they must be shaped by on-the-ground realities and economic contexts. Many of the issues these policies can address—water quality, road congestions, landfill waste, and even greenhouse gas emissions—are most relevant at the local and provincial level. Over the next five years, Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission will examine specific ecofiscal policies to address these issues across Canada’s diverse regions. In doing so, we aim to broaden policy-makers’ tool-kits with pragmatic solutions for achieving economic and environmental prosperity.

Photo: Shutterstock