“The past is a foreign country,” wrote an otherwise obscure English novelist, L.P. Hartley, “they do things differently there.” An American scholar, David Lowenthal, borrowed the phrase for a book that distinguishes between history and heritage. History, he suggests, is the past; heritage is what we make of it. You see the difference at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, at Old Fort Henry in Ontario and in the Secondary 4 history exam in Quebec. We start with a concern for the past; we finish preoccupied by a concern for politically-correct interpretation, for attracting paying visitors, for ensuring that values and concepts approved by ministries, boards and editors have been memorized by the young. Heritage is the CBC re-trying Louis Riel using modern laws and a sympathetic “judge” to do its best for his acquittal. The realities of 1885 were too complex, apparently, for modern Canadians.

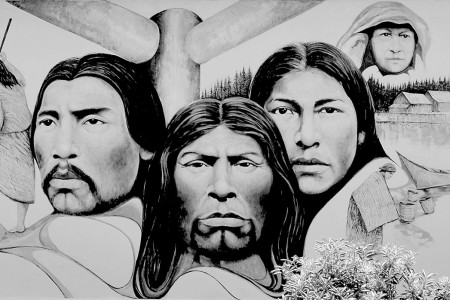

The past does not change, but its interpretation can alter radically. In Quebec, for example, Laval’s Jocelyn Letourneau offended nationalists by arguing that their cause has largely been successful. Confederation, with its deep diversity, has worked. French is stronger. There is, in contemporary Canada, both “sovereignty and association.” More radically, Gérard Bouchard’s proposed “Américanicité” invites us to trace our roots from America’s first people, as is common in Mexico or Peru, rather than from European ancestors. This does not change history but it certainly alters the perspective and the “us.” Both Bouchard and Letourneau use history as a feedstock for challenging heritage. Both use the past to interpret the present, for reasons that are not hard to understand. And neither is utterly new. Marius Barbeau, T.F. McIlwraith and other Canadian ethnologists in the 1930s antedated Bouchard’s arguments, and George Brown, George Stanley and other English-speaking historians denounced the doom-laden teaching of Lionel Groulx’s disciples in the so-called Montreal School. History is perennially new, and faithfully old.

Back in 1997, the Donner Foundation financed the young Dominion Institute to hire pollsters from Angus Reid to ask more or less the same kind of questions of 1,024 Canadians, 18 to 24. The results, announced on Canada Day, 1997, were more or less what reporters usually discovered when the city editor sent them up to the campus on a quiet day in the newsroom. Most Canadians had no idea when Confederation happened. One third could not even place it in the right century. Most (63 percent) knew that Macdonald was our first prime minister, though in Quebec awareness dropped to 28 percent. En revanche, 79 percent of Quebecers but only 33 percent of New Brunswickers knew that Wilfrid Laurier was our first francophone prime minister. Two out of five in the sample imagined that Canada had fought France, Britain and Russia during the two world wars. No one could define “responsible government.” No one dared ask the question.

Later that year, on the 50th anniversary of Citizenship Day, 1947, the Institute announced that 45 per cent of 1350 Canadians had flunked a standardized 12-question citizenship test. Respondents could not name all three of the oceans that border Canada or the event that brought the original provinces together. Most thought that Canada’s head of state is the prime minister. And the tests keep coming. A Remembrance Day quiz revealed that some Canadians believed WE attacked Pearl Harbour! Some kind of wish fulfillment, perhaps. In ensuing years, Canadians got used to a twice-yearly Institute reminder that “we haven’t a clue” about ourselves.

Canadian ignorance of our history is commonplace, and not just among professors. Politicians and business leaders repeat the mantra. My friend and co-author, Jack Granatstein, won best-seller status for a little book claiming that Canadian history had been killed, mainly by academic social historians and educational bureaucrats, though, as cultural commentator Robert Fulford pointed out, no one is entirely free of blame—except Jack.

None of this, incidentally, is new in—or unique to—Canada. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan sympathizers found the same lamentable ignorance among Americans. Two-thirds of them couldn’t date the Civil War and one-third put it in the wrong century. British studies in the Thatcher era found similar bad news. The difference is that people here started to do something about it. Canada’s National History Society, the people who publish The Beaver in Winnipeg, persuaded Rideau Hall to issue Governor General’s awards to outstanding school history teachers. Charles R. Bronfman’s CRB Foundation had worked for years on “Heritage Minutes” and other ways to inform Canadians about their history. In 1999, the Bronfman-funded McGill Institute for the Study of Canada held a national conference called grandly “L’avenir du passé / giving our past a future.” By coincidence, the former CEO of Bell Canada, Lynton “Red” Wilson, had pledged $500,000 of his own money to revive history in Canada, perhaps using new technologies in which his firm was expert. That led to a merger with the CRB resources and an organization called HISTOR!CA.

To be fair, though Jack Granatstein is a friend, I never believed that Canada’s history was dead. I grant that it lacks the bloodshed and myth-making of some national histories, but I think that mass murder is shameful and myths are often nonsense. I knew from experience that history was hard to teach, but rejoiced that there were some very fine and successful teachers to emulate, most of them in Canadian high schools. As Quebec’s minister of education, Madame Pauline Marois promised that she would teach her sons to cook, if their schools taught them about the past.

People also kept telling us that Canada’s history is worth knowing, even sometimes fun. When Canadians curl up with a good non-fiction book, chances are fifty-fifty that it will be about history. Huge audiences stayed glued to televised versions of the US Civil War and the histories of baseball and jazz. A history channel was such a success with US audiences that the CRTC gave quick approval to Canada’s History Television channel, and then to a Canal d’histoire. For more than $25 million, the CBC and Radio Canada staged Canada: A People’s History, its most popular series in years.

So why the gloom? One common thread linked Reagan, Thatcher and the Donner Foundation. All were, in contemporary terms, conservatives, and a conservative is often someone who thinks the past is preferable to the present and probably to the future. This is an interesting but utopian position, since the past is a place we can never really revisit, however hard we try, any more than we can ever predict the future. Conservatives need the past as a guidepost. Would Canada really be falling apart if Canadians really understood our history? Would Québécois have voted No if they had really memorized all those cruel episodes of victimization? Would Canadians be as alienated from their political system as they seem to be if they—and perhaps current practitioners—understood the rules and how to make them express legitimate concerns?

History, said Henry Ford, is “more or less bunk.” In the sense he had learned it, he was probably right. Whatever Ford meant, post-moderns know that there is no single “true” history, only many personal versions, some of which are chosen by education officials and “approved for childish consumption.” The Dominion Institute’s solution to the ignorance it discovered was to be a collection of free-floating “National Standards,” purged of any troubling or debatable context. Is knowing that Confederation happened in 1867 or the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919 “history” or simply an almost meaningless fragment of an event, a factoid as easily forgotten as memorized?

Ironically, in a debate about history, there seems to be little awareness of the history of teaching history. Public education was a 19th century invention, designed to create loyal, dutiful citizens, and history was its sharpest blade. Properly trained young men would be patriotic conscripts in the ranks of national armies, and patriotic women would cheer their son’s departure to the latest national war. No wonder provinces have watched over this aspect of education with a special passion. Years ago, when I agreed to write a book for BC’s Grade 11 history program, a colleague reminded me of a predecessor. As headmaster of Upper Canada College and a decorated veteran who had left a leg in France, W.L. Grant must have seemed an ideal man to write BC’s first Canadian history text. But when he dared to explain why Quebecers had refused to support conscription in 1917, his book was promptly scrapped. As I adjusted to historical pronouncements from Victoria, Grant came often to mind.

Heritage-making may explain why approved versions of our history have, in Maurice Hutton’s phrase, been as “dull as ditchwater.” As a member of the famous Massey-Lévesque Commission on Canada’s culture, Professor Hilda Neatby reserved special venom for school history, a foretaste of her book, So Little for the Mind. In 1962, Northrop Frye told the Toronto School Board that not much would be lost “if history, as presently prescribed and taught, were dropped entirely from the curriculum.” A decade later, in What Culture? What Heritage? Bernard Hodgetts published a savage denunciation of how young Canadians were taught their history. Professor Ken Osborne, a veteran of the history and social studies scene, concluded in 1996: “It seems reasonably clear that most students are not being led to think about the Canadian past in any coherent or systematic way.” Osborne added that he knew of no “golden age” for Canadian history teachers or learners.

Translated, revised, purified and modernized, school history is obliged to pay homage to the current adult orthodoxy, be it British imperialism, papal authority, Marxism, bilingual multiculturalism, feminism or the George Bush world view. This is not new. Confederation happened at a time in Western civilization when school-based history had provided the core of civic education for future members of a mass electorate. By assigning education to the provinces, the authors of Confederation ensured that there would be no pan-Canadian orthodoxy. Jack Granatstein wants a unifying national history. Could Canada survive the “History Wars” other countries have experienced?

As pain-averse professionals, most official educators outside Quebec have preferred to diminish history to the smallest possible compass. Post-modern doubts about the “accuracy” of history have accelerated their urge. Much that makes history fascinating, and perhaps even educational, tends to outrage an authoritarian. If history is not true, how dare you teach it to the young? The answer, of course, is to invite close study of the same rules of evidence and human behaviour that a citizen should learn to apply to commercial advertising, political speeches and ministry circulars. End of argument!

Through the study of history, students could learn “historical understanding”: the fundamentals of causation, sequence and relationships that distinguish “history” in its full intellectual rigor from that magpie’s nest of diamonds and baubles called “heritage.” Such an approach, as Quebec’s leading popular historian, Jacques Lacoursière, argued in his 1997 report to the provincial government, is rich in the skills which preoccupy contemporary educational policy-makers. In the report of his working group, Lacoursière summarized the benefits of teaching “historical thinking.”

It is through history that we understand the mechanisms of change and continuity, and the many ways in which problems are posed and resolved in society. We learn to recognize and weigh the different interests, beliefs, experiences and circumstances that guide human beings inside and outside their own societies, in the past and in the present. History enables us to understand how such interests, beliefs and experiences drive human beings to construct knowledge, and makes us aware of the value of knowledge and of its relative nature.

In history, as in much else, much more is taught than is learned. Assuming we had the power to inspire learning, what would we seek from history?

- Appreciation of the continuum of past, present and future. Almost nothing is totally without precedent, though the circumstances will be only imperfectly recalled. That imperfection, aggravated by the subjectivity of time, space and circumstance, is as important to teach as whatever purports to be an interpretation of the past. Time-past, time-present is a philosophical concept, by no means self-evident to the very young, any more than that other historical concept, cause-and-effect. Yet it lies at the core of civic reasoning.

- Awareness of cultural, ethnic and family heritage. Canadians are not members of a rootless society. People have lived here for at least twenty millennia, and we or our ancestors have come here from somewhere else, bringing experiences and culture with us. Canadians need to recognize the common experiences that form our culture and we need a sense of the heritages with which we share our country. We need to know about minorities and about majorities too. History provides the means.

- Understanding how and why our society has evolved. We need a kind of “user’s manual” understanding of Canada, our province and our community. We should know how the workings have changed over time, sometimes by external pressure, sometimes because individuals no greater than ourselves have pressed for change. This is sometimes described as “civics,” but history is not limited to the framework of democratic institutions and government. History extends to business, industry, financial institutions, unions and the multiple organizations of civil society.

- Knowledge of our world. However unsatisfying the state of Canadian history may be, world history has virtually disappeared from school curricula save as seldom-taught electives. Yet we live in an inter-connected world. The ancestral roots of our own people, communications media and our own economic past, present and future make Canadians part of that world. If ignorance of our own country is disturbing, ignorance of the world is dangerous. Lacking any sense of world history, our collective responses to the world are frequently childlike. Contemporary history will provide you with examples.

Having defined some of the benefits we expect from a greater understanding of history, how close are we to these goals? Can we come closer? Can we persuade teachers, students and, above all, their elected and appointed bosses, of the value of “historical understanding”? Can we convince Canadians to broaden their array of historical perceptions? Can we make better use of existing and potential media and resources? Any exploration of the problems of learning, understanding and sharing history, such as happens annually at Histor!ca’s teachers’ institutes, reveals hundreds of good ideas, some contradictory, some mutually reinforcing, all worth sharing.

The obvious complications of mobilizing nationwide interest in a diverse set of provincial curricula could be met by a national organization of Canadian history teachers, sharing experiences and techniques, developing resources, and expanding the interprovincial consortia which have emerged in both Western and Atlantic Canada. A national association could also support and encourage professionalism among history teachers, who otherwise are among the most exposed and vulnerable members of their profession.

History in Canada seems to me to be very much alive. It is also full of challenging uncertainties and fresh ideas. It is grabbing a larger market than the readership of academic monographs. Between the CBC, Histor!ca, History Television, The Beaver and countless local, provincial and federal initiatives, it is passing through a vigorous era. A national history teachers’ organization could consolidate some of the gains.