The usual Canadian peace on immigration has been shattered with major proposals from the Conservatives and the Liberals. One Conservative leadership hopeful, Kellie Leitch, has endorsed testing would-be immigrants for “anti-Canadian values,” while another, Steven Blaney, wants to ban the niqab. On the other side, the Liberals have considered massively increasing immigration rates. Setting aside the moral standing of these proposals, what do Canadians think about immigration and what does it imply for public policy?

Three things are clear from recent public opinion data: first, many Canadians, one-third to two-thirds depending on the issue, agree with Leitch and Blaney and want policy action on immigration and minorities. Second, if the Conservative Party endorses these policies, it will lose the next election. Third, there is little support for increased immigration, but government policy has often ignored public opinion on immigration.

My research on attitudes toward immigration and minorities, drawing on both the Canadian Election Studies and private sector polls, shows a rough “rule of thirds.” About one-third of Canadians hold clearly negative views. They want less immigration. They have less positive views of racial minorities and they think less should be done for minorities. Another third want more immigrants. They favour diversity and they reject policies that target specific groups such as Muslims.

The middle third of Canadians are “conditional multiculturalists.” They favour immigrants if they adopt Canadian values. They might favour restrictions on the niqab in citizenship ceremonies, but not in all public life. They worry Muslims pose a security threat, but they also think Muslims deserve equal treatment. How the issue is framed matters — as anti-immigrant and racist, or as a reasonable policy to protect Canada.

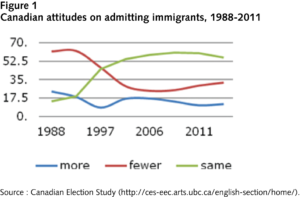

Attitudes do change. Between 1995 and 2005, opposition to immigration dropped by about 20 percent, as the figure below shows. This was a large and long-lasting shift in public opinion. However, this was almost entirely a shift from wanting “less immigration” to wanting it to be “about the same as now.” Support for more immigration was virtually unchanged. A good part of this shift was likely caused by improvements in the economy. Research on attitudes toward immigration has shown that perceptions of economic competition affect opinions about immigration. During this period unemployment dropped from 11.3 percent in 1992 to 6.8 percent in 2007 — a 32-year low. Despite an increase after and during the 2008 recession, unemployment has hovered around 7 percent and support for current immigration rates has been relatively steady. However, a booming economy doesn’t equal a desire for more immigration. When times are bad, Canadians want less immigration, when times are good, they accept the status quo.

Thus, there is little support for increasing immigration: only about 10-15 percent of Canadians want more immigration, and as the figure shows, that number has hardly budged in the last two decades. But this has not stopped previous governments from going ahead and increasing immigration anyway. The Mulroney government massively increased immigration from 84,300 immigrants in 1985 to 256,600 in 1993, essentially ignoring the consistent 60-70 percent of Canadians who thought immigration levels were already too high, according to polls at the time. In fact, government policy on immigration has always been remarkably unyielding to public opinion.

The Liberals are clearly concerned that massively increasing immigration levels could provoke a backlash. The Advisory Council on Economic Growth, headed by Dominic Barton, proposed increasing immigration levels by some 50 percent, and Immigration Minister John McCallum initially seemed to support a substantial increase. Later McCallum said this might be too ambitious, citing public attitudes as an issue. There is some reason for that concern: a significant number of Canadians oppose increases to immigration, and significant policy change might strengthen that sentiment. Stagnant job growth does not help. As noted, a good portion of support for immigration depends on economic circumstances, and perceptions of increased competition for jobs might well change opinions.

Public reaction also depends heavily on how other parties and the media respond. It is an axiom of public opinion research that the issues that matter most are those that are top of mind. Canadians might disagree with the Liberals about immigration policy, but they have many other concerns. If the opposition parties and media look elsewhere, so will voters.

However, Leitch and Blaney have realized that the support of one-third of Canadians is enough to win the Conservative leadership. Not coincidentally, polls show that two-thirds of Canadians agree with Leitch, and her support doubled soon after taking those positions. Those with longer memories will recall that at Reform Party rallies, opposition to multiculturalism always produced loud cheers. This strategy could be successful.

Yet, this position also courts political disaster. Only one-third of Canadians back such a message. The Canadian establishment is quick to call such policies — and the party that proposes them — racist and extreme. And conditional multiculturalists do not want to support allegedly racist policies. This reputation is part of the reason why Reform and the Canadian Alliance could not form government. In addition, the political geography of Canada means that winning elections is practically impossible without ridings in British Columbia and the Greater Toronto Area that have large numbers of immigrant and minority Canadian voters. If the Conservative Party is perceived as the anti-immigrant party, it will likely lose these ridings and the election.

In government, the Conservatives might be able to nuance their message. Recall, even Justin Trudeau voted in favour of Bill S-7, the Zero-Tolerance for Barbaric Cultural Practices Act. But in opposition the Conservatives don’t control the agenda, which limits their ability to influence how these policies are framed. In the best of times, these are risky policies.

Former prime minister Stephen Harper and his multiculturalism minister Jason Kenney knew this, which is why they avoided overt anti-immigrant appeals — though this changed slowly over their decade in power. Confronting “barbaric cultural practices” failed to save the party in 2015, and it will not save it now. Leadership candidates appeal to the base, but the party must then live with the consequences. Recent comments by Kenney, Rona Ambrose, Maxime Bernier, Michael Chong and others suggest they recognize this danger.

But what if the Liberals proceed with a massive increase in immigration, while the Conservatives decide to oppose it? The Conservatives might still lose at the ballot box, but this combination is a recipe for potent social conflict. Those opposed to immigration would fiercely resist, and their position would be legitimized by the support of a major political party. Such a major increase in immigration would be easier to oppose without being seen as racist, thus attracting conditional multiculturalists. The outcome of this would be highly uncertain, in part because there is no precedent in modern Canadian history — the major political parties have never taken those positions at the same time. If that changes, even “tolerant” Canada might experience the sentiments now seen in Europe and the United States.

The author recently presented the research discussed here, with Erin Tolley, at “Frontiers in Public Policy: Federalism and the Welfare State in a Multicultural World,” a conference held September 23-24, 2016, by the School of Policy Studies at Queen’s University.

Photo: Fred Thornhill/The Canadian Press

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.