Whisky is fer drinkin, water is fer fightin, over…

Mark Twain

Aleppo is a glorious city in the north of Syria. The rich carvings on the honey-coloured stone buildings are reportedly the work of the generations after those who carved Solomon’s temple. “It feels like it should have a river,” I commented, on my first visit. “Oh, we had one long ago,” said my friend, “but the Turks took it.” He added: “So we diverted one that used to flow into Turkey, further east down there, toward the Mediterranean.”

Later, a few kilometres away, I descended into an underground tunnel more than five metres below the surface, wide enough to walk in. Built centuries ago by one town because the neighbouring town was polluting, it tapped further upstream into the water source over which the two towns couldn’t agree. The existence of slave labour at the time of construction undoubtedly made deviation an easier option than negotiation.

Are these historical examples the real story of the way the world manages and resolves water problems? Sometimes, but not often. Are they representative of the way we fail to manage water? Well…let’s look at that. Is anyone in charge of our water? Decidedly, no.

Water is the essential underpinning of life. No water, no life. It takes a litre of water to create every calorie we eat; water plays a key role in our religions and in our recreation; it can create energy, provide transport and remove waste.

It would be reassuring, given water’s indispensability, to think that there are shared, complex and well-understood systems for arbitrating water disputes within countries and between countries, preferably presided over by respected institutions and judicial authorities whose word is taken and obeyed. Mostly, this is not the case.

With some notable exceptions, the amazing thing about international water governance and effective water dispute resolution mechanisms is that, more often than not, they are not there.

The existence and functioning of international institutions tend to mirror the existence and functioning of national systems. We have ministries of health and the World Health Organization, ministries of agriculture and the Food and Agriculture Organization, weather bureaus and the World Meteorological Organization, legal ministries and a series of international courts, commerce departments and the World Trade Organization — and so on and so on. The main reason we don’t have effective international institutions for water is that in most countries, we really don’t have adequate national arrangements.

Most countries do not have a ministry of water. Where there is a minister responsible, it tends to be the minister responsible for the greatest water use — the ministry of agriculture and irrigation, or the ministry of environment. This is changing, particularly in dry countries. Sometimes where there is a water minister, he or she has no regulatory or budget allocation power.

Nationally (and internationally) there are centres of excellence and expertise for many facets of water management — drinking water, sanitation, desalination, safety standards, waste water treatment, hydro generation, water transport and transportation. Some would say there is a plethora of such institutions. But in fact there is a paucity of organizations — nationally, in the first instance, and certainly across boundaries — that integrate water demands: assess the implications of one water action on another, coordinate, allocate and then arbitrate.

How can this be? We depend on this for life! Arithmetic, my dear Watson. Until the beginning of the 20th century, the human population did not exceed a billion people. Although we have the same water on the planet as did the dinosaurs or Julius Caesar, the per person, vital on-the-spot availability of water went into precipitate decline as the global population rose to 2.5 billion at the midpoint of the 20th century, moved on to 6 billion by the end and is now surging up toward a levelling-off point around 8.5 or 9 billion just beyond the midpoint of this century. Our water laws, rules and institutions, and our religions, myths and views about water derive from this time of “more water than people.” The reality has changed for many populations — and in many places in the world it has changed in our lifetimes. We simply have not caught up with the new reality — and it is difficult, very difficult, to do so.

Moving toward the conscious, transparent, public allocation of available water is a fraught process that is almost guaranteed to generate more enemies than friends for the party doing the allocating. There is strong resistance to giving up water, or even restricting the amount available. Agricultural communities usually have political power well beyond their actual percentage of the population. The move toward charging for water services gives opposition parties an instant election issue. Getting neighbours to manage across boundaries and agree to share the benefits of water, often among people with centuries-old traditions of-mistrust, is not easy.

Good water governance requires that public authorities play an active (and often very unwelcome) role — whether within or across national boundaries — in many areas, including the following:

- Establishing water law

- Setting a regulatory framework

- Allocating water

- Managing inspection functions

- Deciding on and protecting the environmental share

- Ensuring data collection, retention and distribution

- Managing the public debate on issues

- Managing communication on water issues

- Providing subsidies for the poorest populations

Unfortunately, even within countries coordination and arbitration is often difficult and increasingly so. For instance, between Indian states there are acute and difficult conflicts, and in Australia the lack of solidarity between states on water issues necessitated the renationalization of the Murray Darling Authority in 2008. In Argentina, the situation is such that rational national water planning is a somewhat hollow vessel. How then can this paucity of the basic requirements be translated into a smoothly functioning international arbitral system?

Our water laws, rules and institutions, and our religions, myths and views about water derive from this time of “more water than people.” The reality has changed for many populations — and in many places in the world it has changed in our lifetimes. We simply have not caught up with the new reality — and it is difficult, very difficult, to do so.

Human beings are a creative and inventive lot. In Canada we have created governance mechanisms on three, if not four, levels: in addition to the federal government, the provinces, Aboriginal territories and municipalities have regulatory and legal responsibilities for water. In Canada and the United States there are more than 15 national government ministries with the statutory power to make water laws, rules and regulations. At issue is not the sectoral expertise; the question is where and how these are pulled together and who arbitrates when problems arise.

If we haven’t yet developed a world where water is being governed nationally, in most countries is it not a bridge too far to expect that there will be a capacity to perform these functions internationally? In fact, international treaty obligations have often been useful for chivvying domestic compliance on a number of disparate issues, and they have been the precursor to effective domestic legislation.

The world’s 263 international shared watercourses generate about 60 percent of global freshwater, and they cover almost half the earth’s land surface. They run through 145 countries, and around 40 percent of the world’s population lives nearby. The number is not declining: when the Soviet Union dissolved, what were formerly internal rivers became international waterways.

River basin mechanisms pose very real challenges to the existing administrative order. Language, culture, different policies may be involved. The river itself is not the whole story: groundwater, rainwater, aquifers, lakes and land management must be added. National action must be coordinated with actions at the local or regional levels, often in situations where there are no mechanisms for such coordination.

Canada and the United States have two international treaties that affect our shared water resources: the Boundary Waters Treaty, concluded in 1909, and the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, concluded in 1972. In both cases, issues and disputes arising under them are settled by the International Joint Commission, a body made up of an equal number of Americans and Canadians. By and large, it works.

Other regions have very advanced institutional arrangements. The European Framework Directive on the Maas, Scheldt and Rhine river basins has served as an example of a positive approach, engendering cooperation and setting objectives across the borders of member states or, in the case of the Rhine, even beyond EU territory. While several member states already have a river basin approach, this is at present not the case for all European Union countries. It is specified in the framework directive that under the system of river basin districts — some of which will traverse national frontiers — a river basin management plan must be established for each district and updated every six years, and this plan will provide the context for the coordination requirements.

Globally, there are almost as many models of transboundary river relationships as there are rivers, ranging from almost no formalized processes to statistic and information gathering (for example, in Central Asia), development and investment projects (for example, in the Nile Basin) or specific-purpose arrangements such as pollution abatement (in the Danube). One continuing issue is the lack of incentive — resulting in non-membership — for upstream states to participate in these arrangements, for example, Switzerland in the Rhine (though it has observer status) and China in the Mekong. Among these arrangements there are no arbitral tribunals, other than those that may be included in agreements, for shared waters. And there is not much in the way of established law.

Lack of coordination between states poses major threats to the people, ecosystems and economic activities that rely on the long-term sustainability of the water. It can, for example, reduce the availability of water or cause significant levels of pollution downstream. It can also prevent weaker states upstream from getting their fair share of the resource, or it could hamper the ability of migratory fish to reach spawning habitats within headwaters.

According to the World Wildlife cooperative management frameworks exist for only about 40 percent of the world’s international watercourses. Where there are agreements, 80 percent of them involve only two countries, even though other states may be part of the river basin in question.

In 1997, more than 100 nations, including 38 co-sponsoring states, voted in the UN General Assembly to adopt the United Nations Watercourses Convention — a legal umbrella agreement that establishes basic standards, procedures and rules for cooperation between states on the use, management and protection of international watercourses. It aims to:

- Facilitate and inspire negotiations on future regional or watercourse agreements and support the implementation of existing treaties;

- Govern international watercourses in the absence of applicable bilateral or multilateral treaties;

- Supplement multilateral environmental agreements, such as the conventions on climate change, biodiversity, desertification and wetlands;

- Advance international policy aspirations like the Millennium Development Goals; and

- Offer a basis for the codification and development of international water law at the global level.

The convention today includes 17 contracting states — 18 short of the number required for entry into force.

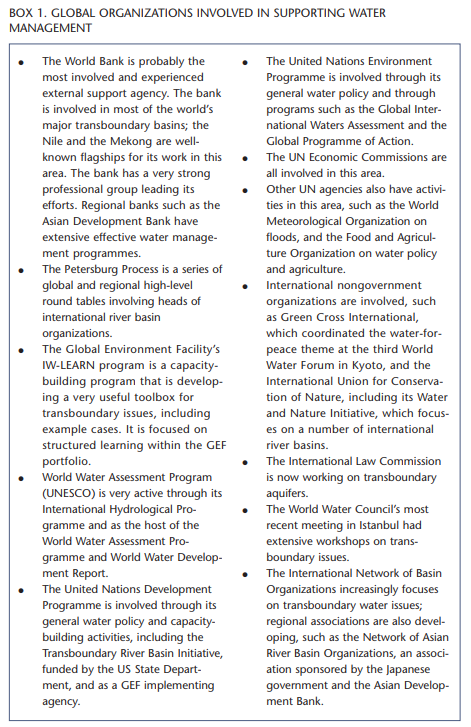

Given the situation on the national level, it should not be too surprising that there is no international organization for water, even though 21 UN organizations all have water programs and responsibilities — just as do their domestic counterparts. UNWater brings together more than 20 UN bodies in periodic assessments; it produces guidance materials and attempts to monitor some aspects of the global water situation. But it does not in any sense manage international relations over water. Partly as a result of this body’s lack of real management authority, there are a plethora of other global or regional water organizations (see box 1 for a list of these actors).

The role of these supporting actors is to provide technical and financial assistance to the primary actors, generate and disseminate knowledge, and promote good practices. They include multilateral agencies, such as the UN system, the World Bank, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and regional banks, and also bilateral donors. Most of these agencies take a strong interest in transboundary water issues as part of their water programs.

Do nations go to war over water? It is absolutely the case that two Middle Eastern cities armed themselves and went to war directly over water. But that was 4,500 years ago, and in the years since then actual violence has largely remained at the local level. Although in the last century there have been a few instances where armies were mobilized and shots were fired, generally nations have found more reason to cooperate than to fight over water. In some regions there is a fairly rich tradition of transboundary cooperation. India continued to pay Pakistan for the costs of building and operating dams, which Pakistan continued to build and operate, right through several periods of India-Pakistan hostilities. The Mekong River treaty held, with some problems, right through the Vietnam War. The Jordan River treaty is more observed than it is violated, though it is on occasion violated.

Aaron Wolff at Oregon State University is the ranking guru in this area. His study of the water issues over the past 50 years shows that two-thirds of all events involving two or more states have in fact been cooperative, and that acute violence is rare. Where there is violence, the issue is usually a subset of other difficult issues. US intelligence reports suggest that water shortages have often stimulated cooperative sharing arrangements.

But transboundary issues are complex. They are often not about water availability alone. There is a rich mixture of issues that will continue to plague the 261 countries that share river basins: water dumping in times of flood risk, existence of toxic dumps near water sources, inadequate industrial protection, salinity and agricultural waste in the stream, building dams and infrastructure without consultation. Climate variability adds to the complexity of this mix.

Thus as countries come up against tighter and tighter limits, conflict could increase. Wolff’s axiom says, “The likelihood of conflict rises as the rate of change within the basin exceeds the institutional capacity to change.” In other words, in some cases, the strong linkages, history, technical capacity and managerial competence will help find solutions to new challenges. Canada-US relations are a case in point. In other cases, in the Aral Sea region for instance, it is much less likely that solutions will emerge easily given the weak linkages between the bordering states.

Water pollution and overuse of water are increasing almost everywhere, and the world’s poorest people are already facing shrinking water supplies. Climate change is increasing the pressure on water resources and making water availability less predictable. Most of the world’s transboundary river basins still lack adequate legal protection. For all those reasons, more than ever before we need effective and widely applied norms. The progress toward them is very slow indeed.

Photo: Shutterstock