For Canada, the heart of the initial Canada-US free trade negotiations was a binding, binational system of dispute settlement. The greatest risk to our trade with the United States, then and now, was arbitrary or capricious decisions that curtailed our market access. Or, if you like, sheer protectionism. The solution devised to resolve disputes in the free trade agreement (FTA) broke new ground and was replicated both in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). It has not been a universal fix by any means, but it has moved matters in the right direction.

The objective for any trade negotiation is to create greater certainty for exporters and importers alike, enhancing market access on mutually beneficial terms and ensuring nondiscriminatory treatment for the parties to the agreement. In that respect, the FTA and NAFTA have served us quite well over the years.

Perhaps the best compliments are that the dire predictions from those in Canada who had been opposed did not materialize. In fact, many politicians who vigorously fought against the agreements while they were in Opposition became fervent champions once in government.

The trade results were even better than we had expected. Canada-US trade almost tripled in the first decade. Industries that were to have disappeared — like Ontario and British Columbia wine — have flourished. Clothing manufacturers — like Peerless — were reportedly doomed. Peerless is now the largest manufacturer of men’s suits in the world.

In terms of what was missed in these negotiations, the agreement on government procurement was limited primarily because our provinces were reluctant at that time to accept a broader discipline — a major reason, incidentally, why we continue to suffer from “Buy America” initiatives from the United States Congress.

There were other exemptions within the agreement — a triumph of political pressure over economic theory, which is the inevitable “trade-off” in any trade negotiation. Many exemptions were in the agriculture sector, which is why I tend to regard “agriculture trade” as an oxymoron!

While, on balance, the economic results have been positive for all three parties, what I regret most is that NAFTA has not served as a template for broader free trade initiatives. That had been the intent. Instead, each NAFTA partner chose to go its own way, first with Chile, subsequently with Central America and Colombia and, more recently, with more distant markets in Europe, Asia, the Middle East and Africa. That has prevented us from using our combined leverage to mutual advantage.

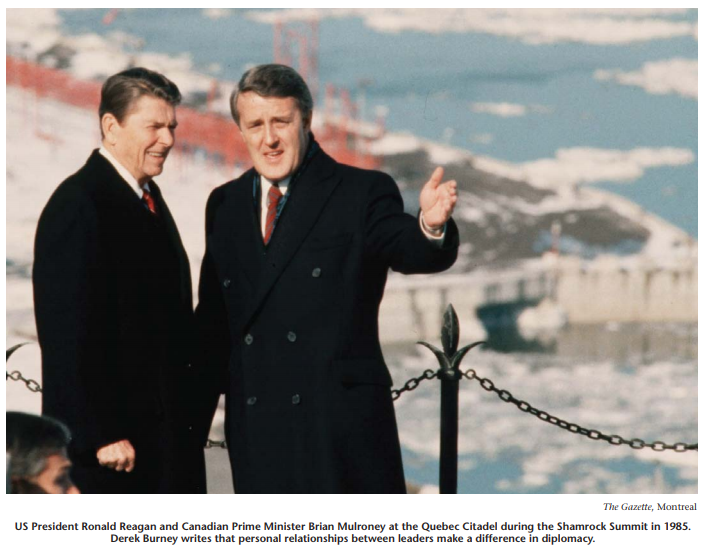

I am often asked whether personalities make a difference in diplomacy. The stock answer invokes Lord Palmerston to the effect that nations have no permanent friends, only permanent interests. But, on some notable occasions, the Canada-US relationship has been the exception to that rule.

Initially, neither American nor Mexican officials and politicians wanted Canada in the NAFTA negotiations. Both feared that we might complicate and delay matters.

It was only the excellent personal relationship between Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and the first President George Bush, in particular, that enabled us to override those objections, just as it had been Mulroney’s relationship with President Ronald Reagan that helped us salvage the free trade negotiations at the last minute.

The objective for any trade negotiation is to create greater certainty for exporters and importers alike, enhancing market access on mutually beneficial terms and ensuring nondiscriminatory treatment for the parties to the agreement. In that respect, the FTA and NAFTA have served us quite well over the years.

Leaders can be very influential in getting things done. Equally, when the leaders are not engaged, not much of consequence happens on the bilateral agenda. Let me illustrate.

Despite the initial benefits from the FTA and NAFTA, trade between Canada and the United States has stalled in recent years. After 9/11, and in the name of security, many new inspection and vetting procedures were added at the border by the United States. These have stifled the flow of trade and the efficiency of intracompany production in North America. The more recent financial meltdown and prolonged recession only compounded the problem.

Of course, 200 years ago, the Canada-US border was even more fractious. Who won or who lost the War of 1812 may still be a matter of debate, but what I do know is that the Americans captured Montreal and gave it back. The Canadians, along with the British, captured Detroit and gave it back. Readers can decide for themselves who got the better deal in that exchange.

In Canada, we recognize that much of our economic future hinges on a more robust US economy. Forty percent of our bilateral trade flows from highly integrated industries on each side of the border.

What Americans sometimes forget is that Canada remains the United States’ largest export market, and by a wide margin. (Mexico is number two and China is number three.) Nurturing, persevering, and enhancing the value of what we make and trade together will always be a matter of priority and vigilance for Canada. It should be for America as well.

What Canada and the United States are now doing most notably together represents, not surprisingly, a new effort to reduce impediments at our shared border.

The Beyond the Border initiative announced last December by President Barack Obama and Prime Minister Stephen Harper is intended to expedite, rather than frustrate, legitimate movements of people, goods and services, thereby improving the efficiency of what we make and sell to one another while shifting the security focus more to those who pose a real threat and to cases of illegality or fraud.

A parallel effort is underway to inject some common sense into the cumbersome regulatory regimes used for much of what we produce and trade — from duplicative safety inspections for autos to redundant, overlapping standards for food and pharmaceutical goods. Separate standards in the name of health or safety — what some have called the “tyranny of small differences” — can give much scope for mischief.

The biggest obstacle to progress on border impediments or regulatory reform will, in fact, be bureaucratic inertia, a rigid dedication to the status quo — the “iron rice bowls” fiercely guarded by those involved.

The Beyond the Border initiative would not have happened without a strong prod from our two leaders. It is still a work in progress and will not fulfill its objective unless that firm leadership is sustained.

The saga of the Keystone XL pipeline project offers a very different example of leadership. Because the pipeline intends to cross the Canada-US border carrying oil from Alberta to refineries in Texas, it requires a presidential decision on whether it serves the United States’ national interest. After three years of intensive regulatory and environmental reviews and approvals, a positive decision had been anticipated late last year. Instead, last November, in the face of strenuous environmental opposition (including by some Hollywood celebrities), the President postponed his decision until after the elections.

Keystone XL quickly became a political football in the election campaign. Republicans in Congress tried unsuccessfully to force the president’s hand. The President then vetoed the project “in its current form” but invited the company to reapply, which it did in May. When TransCanada announced plans to build the southern segment of the pipeline running from Cushing, Oklahoma to the Gulf, to ease the glut of oil building up in Oklahoma and provide needed supply for the Texas refineries, the President endorsed this development.

If you are a bit confused, imagine what TransCanada executives and those in the oil sector are thinking. (I should mention that I am a director of the company.) Some have suggested that it may be easier to have a pipeline of Canadian whisky to Texas than Canadian oil. And, you will know from history that there was a time when exports of that product were very popular, albeit illegal, in the United States.

What is certain is that the confusion and delay over Keystone has been a serious setback for our bilateral relationship. After all, unfettered trade in energy is a pillar of NAFTA. The President’s actions, prompted primarily by domestic electoral considerations, are seen in some quarters as violating the spirit, if not the letter, of our principal trade agreement.

More fundamentally, the Keystone soap opera is a sober reminder of just how vulnerable Canada would be if we relied exclusively on the United States for trade expansion.

The salutary effect is that, while the United States is and will be an important market for Canada’s energy exports, we now know very clearly that we must diversify our exports. As our Prime Minister said, “we want to sell to those who want to buy our products.”

That is why Canada is now moving aggressively to negotiate with China, India, Japan and Korea, among others. These are markets that have a strong need for reliable supplies of energy — notably oil and gas. Relative to most other prospects, Canada is seen by these countries as a reliable source of supply.

That is why, with the prolonged recession and the virtual collapse of the Doha Round of multilateral trade negotiations, Canada is now scrambling to adapt to the dramatic new opportunities for trade with the emerging markets.

Consider a few statistics:

Canada’s exports to the United States declined from 87 percent of the total in 2000 to 74 percent in 2011, whereas the percentage of our exports to China rose from 1 percent in 2000 to 4 percent in 2010.

China’s GDP reached number six globally in 2000 but became number two in 2010. Some predict that it will overtake the United States and become number one within the next decade.

We are in the midst of a commodity boom, one that contributes mightily to our prosperity. In 2010, energy, minerals and agri-food products were 26 percent of all Canada sold to the world, almost triple the 9 percent in 1998. The increasing demand for these products plays to Canada’s strengths and to our comparative advantage in trade negotiations. It also helps explain why our dollar is so strong. Energy and mining companies are now 8 of the top 20 most profitable firms in Canada. Suncor, at $36 billion in revenues, is larger than two of our major banks — BMO and CIBC.

The manner in which the Canadian government reacts to the proposed $15-billion acquisition of Nexen by CNOOC may well be the acid test to determine whether we will “walk the talk” on diversification and, if so, on what terms.

Both Canada and the US are acutely aware that future growth will depend more on the fast-growing emerging markets — notably those in the Asia Pacific region — than on the slow-growing “advanced” economies. That is precisely why we are witnessing a flurry of bilateral and regional trade initiatives.

In 2011, President Obama declared a strategic “pivot” to the Asia Pacific region, indicating that the United States had both economic and security objectives in mind. It was on that basis that the United States Free Trade Agreement with Korea was concluded late last year. Once the elections are over in America, we may see even more flesh on the bone of this new priority.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is at the core of US thinking, and it is seen by some as the best means to bring greater stability as well as prosperity to the region under new standards of trade liberalization. It has been described as “NAFTA on steroids.”

We are already hearing demands from organized labour in the United States about TPP that remind me of the NAFTA experience. I suspect that if, after November, the US administration decides definitely to move on the TPP front, and particularly if President Obama is re-elected, labour relations will be a key element for the US negotiators. That may not be universally welcomed by all TPP partners.

Long before Lord Palmerston made his often-quoted observation, George Washington declared that “no nation is to be trusted further than it is bound by its interest.” That “self interest” sentiment seems to be in ascendancy these days in Washington. It can be a constraining factor for any negotiation and for the management of any bilateral relationship.

Nonetheless, the basic motive of all these trade initiatives — whether bilateral or regional — is to keep protectionist forces at bay and bring greater balance to global economic growth. That in itself is desirable.

The challenge is daunting but the prospects are immense.

What many of these emerging markets have in common is the extent to which the “visible” hand of government is involved in shaping economic policy. State-owned enterprises in countries like China and Brazil, backed by massive sovereign wealth funds, pose a unique challenge for those of us who were taught by Adam Smith and others to believe in the value of the “invisible” hand of the market. The conventional rules for trade and investment that carried us through the last half of the 20th century may not be sufficient in this century.

How can you ensure a “fair trading system” or a “rules-based system” if some companies enjoy the support, covert and overt, of their national governments?

How do market-based cost-of-capital rates compete equitably with those of sovereign-wealth funds and stateowned enterprises?

How do you protect intellectual property — the catalyst for innovation and productivity — or any technology in countries where the rule of law is more elastic than certain?

China is riding a tiger of sorts on the home front, and the Chinese government’s overriding priority will be to maintain its unfettered political control in order to preserve the integrity and unity of the nation. Continued economic success is essential to that objective.

Free-market economists assure us that the combination of cronyism and corruption will ultimately undermine the advantages of countries where state-owned enterprises dominate. Others hope that, as the middle class grows in these countries, political liberties and a more liberal approach to economic management will follow.

What is certain is that the trade negotiators of the 21st century face challenges those of us from a different era do not envy.

Still, for my money, tangible moves to more open trade are essential tonics for the global economy and, as long as the initiatives are mutually reinforcing, they should be encouraged.

As in labour relations, the best solutions in trade negotiations ultimately come from compromise, a balanced verdict in which neither party gets all it wants but each gets enough to forge a good agreement. Results inevitably reflect a balance between economic theory and political reality.

Looking forward, we in Canada would welcome an America that moves beyond political gridlock in Washington, redresses its fiscal problems and regains its historic sense of optimism and confidence. The challenges cry out for firm political leadership and decisive action.

Because a pessimistic, inward-looking, uncertain America that persists in living “beyond its means” is not good news for anyone. More certain global stewardship by the United States is as crucial now as ever because, frankly, there is no-one else ready or willing to take on this role.

How America responds to a rapidly ascending China will, I suspect, be the major challenge of the next decade.

While many of us — Canadians and Americans alike — would like to see China assume a global role more commensurate with the power of its burgeoning economy, this is not likely to happen anytime soon. China is riding a tiger of sorts on the home front, and the Chinese government’s overriding priority will be to maintain its unfettered political control in order to preserve the integrity and unity of the nation. Continued economic success is essential to that objective.

China is certainly aware that its spectacular 30-year economic transformation is giving it unprecedented international prestige and significant financial power. Centralized control under a state capital model has worked well and is seen by Chinese leaders as the best foundation for stable government and national unity. And frankly, it contrasts sharply these days with the fiscal mismanagement that has paralyzed growth in the industrialized world.

After its brief period of unipolar preeminence, in the future the US may be obliged to act as what Zbigniew Brzezinski has described as a “balancer and conciliator” in relations with China. This will not be an easy adjustment and will require nimble as well as skilled diplomacy by US leaders accustomed to being number one.

Both China and the United States know that neither would benefit from outright conflict. Each has a major stake in keeping the peace while maintaining global stability and an open climate for trade and investment. And, never forget that China is holding $1.2 trillion of US treasury bonds.

Much will depend on the intellect and prudence of the new Chinese leadership team. We can only hope that Beijing’s rhetorical emphasis on “harmony” as the basic principle for domestic and global affairs will be sustained, and that its solitary political system will eventually be broadened by the demands of an expanding middle class.

So, there is a lot riding on the already determined changing of the guard in Beijing later this year and also on the US elections in November, which may or may not usher in a change.

Adapted from remarks to the Association of Labour Relations Agencies.

Photo: Shutterstock