The consensus on Canadian politics today among the Hy’s restaurant hangers-on is that it is a superhighway. Four aging and somewhat battered opposition vehicles trundle down the slow lanes, bumping each other for position. In the fast lane, far ahead, there is a large turbocharged blue Humvee. Only a fool, they sneer, would bet on one of the opposition bangers.

That fool may be vindicated.

The clichés of politics, wielded as wisdom by insiders at the favourite watering hole of Ottawa’s political junkies — that the “race goes to the swift,” that “God rewards the heavy artillery — are their proofs. These and similar axioms have driven the Tory war machine for a decade with irrefutable success. But another important axiom of politics and life is this: nothing lasts. Canadians typically grant their governors two terms in office, sometimes three, almost never four.

The exceptions are places like Alberta or Quebec, where peculiar local factors push democratic choice away from general elections and back into intramural competition — and even they deliver explosive change once every generation or two. Sometimes, parties are so fortunate as to have a succession of amateurs as opposition competitors — Ontario Progressive Conservatives, take a bow — but wise Ontario Liberals know their “threepeat” is as much due to that good luck as it is to good governance.

So the first caution for any federal horserace handicapper is that Team Harper is rapidly approaching its sell-by date. (Friends of the Prime Minister whisper quietly that he would be wise to declare victory, retire and cash in his chip by 2014. If that were to happen, and it seems unlikely, it will be sudden and without warning. It would probably provoke a genuinely savage leadership contest — more 1990 Liberal than 2012 New Democrat.)

The second caution is that the opposition parties have been slowly sorting themselves into a competitive hierarchy. The Greens will fight to defend their one seat and a few small beachheads in Ontario and British Columbia, forgoing the foolish national ambitions of the 2006 to 2008 era. The Bloc will try to double or triple its competitive ridings, but that will only take it into the low 20s.

The two newest and shiniest opposition vehicles on the political highway are orange and red. Soon, each will have new or relaunched drivers as well. Their challenge is to figure out how to overtake the blue muscle car, rather than becoming obsessed with nudging each other into the ditch. Each party has the best chance in many miles to present a serious competitive challenge to the other and to the government.

When Bob Rae is likely confirmed as Liberal leader later this year or early next, he will finally take charge of all the levers of power in the party he joined six years ago. The Conservatives and others will continue to rabbit on endlessly about his personal baggage, but his counterpunches to having been dubbed the “king of debt” for two decades are becoming more and more effective. Even as unlikely a champion as Andrew Coyne recently and brilliantly dissected the facts from the body of political nonsense about Rae’s time as premier. Coyne’s comparison of Conservative federal and Liberal Ontario debt and deficits was sobering for anyone keen to try to maintain the Rae debt attack. He remains a formidable parliamentary and media politician.

The challenge for Ontario is that it seems unlikely the province will recover anytime soon from its long, secular decline, unlike its rapid post-Rae recovery as a beneficiary of the Clinton boom years. This creates a few pretzel-like partisan positions for all involved. Dalton McGuinty cannot respond to anti-Rae Conservative attacks without drawing invidious comparison to his own fiscal nightmare. The federal Tories need to be cautious about laying the wood to Ontario too heavily, as their own deficits set records — significantly due to their own fiscal choices. And New Democrats having sport at their former Ontario leader’s expense risk being reminded that it was an NDP government that sank Ontario’s credit rating the first time — although, while throughout the NDP leadership campaign both Brian Topp and Thomas Mulcair sang the praises of NDP provincial government records of fiscal rectitude, their hosannas often concluded with snide jibes such as “With the exception of one famous example, of course…”

The two newest and shiniest opposition vehicles on the political

highway are orange and red. Soon, each will have new or relaunched drivers as well. Their challenge is to figure out how to overtake the blue muscle car, rather than becoming obsessed with nudging each other into the ditch. Each party has the best chance in many miles to present a serious competitive challenge to the other and to the government.

Mulcair, the NDP’s new leader, now needs to exercise greater self-discipline on this and a laundry list of other areas of previous excess. Rae as well would be wise to resist swiping at Mulcair as a mini-Harper. Such intramural sniping is music to the ears of Harperites, who will do their best to stir the pot, seeking to prevent any form of united opposition against them.

Mulcair has an out for his mixed partisan biography — there were and are no choices for federalists in Quebec provincial politics. He may have been a somewhat blue Liberal in the curious provincial politics of la belle province, but he can always ward off attacks about that history with his federalist shield. Rae’s defence for his shift is not quite so bulletproof, especially if Mulcair succeeds in creating a new centrist political party, stealing the Liberals’ political mojo.

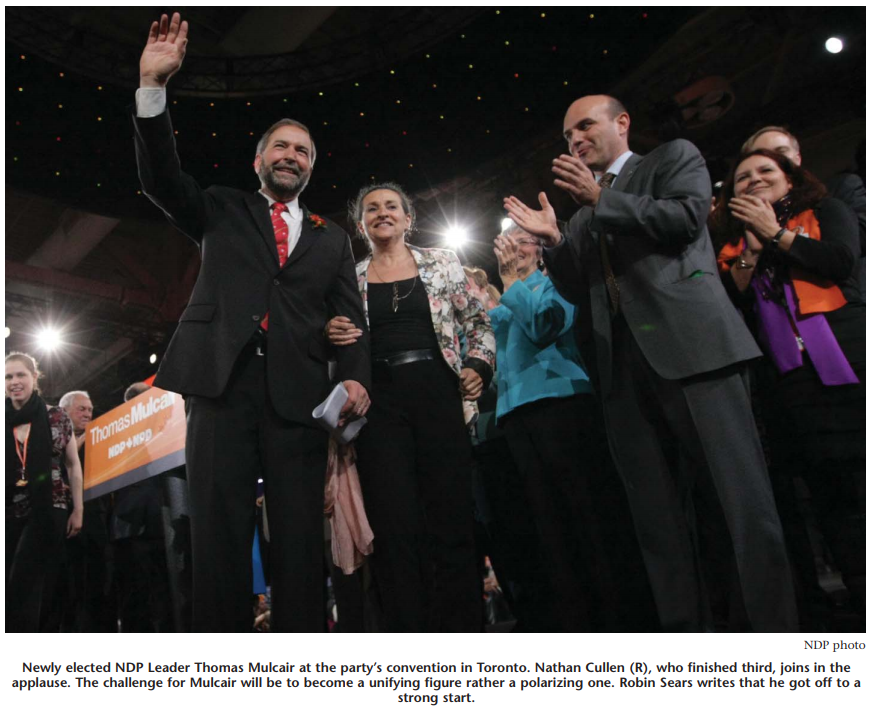

Mulcair was elected decisively, despite solid and widespread opposition to him from the Broadbent generation of party elders — but only on the fourth ballot. He ran a disciplined, even boring, leadership campaign, never letting the angry Tom of old show its face. Under sometimes heavy provocation, he resolutely took the high road in every public event of the gruelling seven-month leadership campaign.

Those who knew his history of a febrile and highly conditional loyalty to colleagues both in the Quebec Liberal party and in his adoptive home; those who had witnessed his predictable tantrums in and boycotts of caucus; those who had seen his explosive spittle-flecked rages at gobsmacked colleagues; and, most importantly, those who knew the nightmares his status-obsessed demands caused Jack Layton up to his final days — all were understandably hesitant about his leadership aspirations.

Very few of them knew of the long and frustrated discussions of first a judicial and then a bureaucratic appointment from the federal Conservatives, and they chose to ignore the whispers as they assessed who could fill the enormous hole left by Jack’s death. With his consummate mastery of the political arts, Mulcair turned his vulnerability into a virtue. He said that he told Jack that every party had flirted with him, but that he had chosen Jack and the NDP, presenting himself as the popular debutante at the political ball. Federal Liberals snorted derisively at the claim.

It remains to be seen whether the Harper Conservatives will be cautious in revealing what they knew and thought of the man they actively courted. My guess is that they will hold back, unless desperate, for fear that some of the mud may spatter their own front-bench MPs, several of whom were involved in the failed courtship. Unless they hold some especially compromising video or e-mail of those failed attempts at political seduction, my guess is that they will try to Tweedledum/Tweedledee the two opposition leaders — playing to the adolescent gallery with sport at a former-Liberal-led NDP and a former New Democrat in the Liberal leader’s chair.

Mulcair is the type of political personality who needs strong staff and collegial restraint — and who usually resists and rejects it. He attempted to get Layton to dismiss several of his senior parliamentary staff team. His own campaign team was nervous about the wisdom of his being drummed into the convention hall when the total time available for a candidate’s arrival, nomination and speech was only 20 minutes. That team was young, green and easily dismissed. Ignoring their caution ruined his opening convention speech, and Mulcair raced through a 12-minute text in six minutes, like a Red-Bulled high school council candidate. The next day he rejected the carefully crafted victory speech the party staff had researched, written and rewritten for each of the prospective winners, and delivered a 10-minute Prozac drone that left his stage mates blushing and network pundits snickering.

That he is a practised and confident political veteran he demonstrated over the next few days, gliding through a potentially fraught caucus meeting, then delivering a flawless media conference performance, then waltzing through his first week as Leader of the Opposition in Question Period. The substance was not Churchillian and the delivery was more angry than statesmanlike, but he was unflappably professional and quotable.

It was the promise of that performance, more than any other factor, that secured his election. As the campaign manager for an opposing candidate justifying his second-ballot support for Mulcair said to an astonished colleague, “Look, he may be an expletive bastard, but that’s what we need to go up against those expletive thugs.” These sentiments were sufficiently widespread that at one point a member of the Layton family mildly asked one of the proponents of the “our bastard” thesis what he thought Jack would have said about that as a ballot question.

It was a curious leadership race from the beginning. Overshadowed by grief and the absent beloved leader through-out, it drew a wide field of not entirely satisfactory candidates. None of the serious candidates was a Ron Paul or a David Orchard, but each had serious flaws in biography or performance. Martin Singh was a poser from day one, and many suspected him of being merely a placeholder for the winner given his curious behaviour at the end — his British Columbia organizer was found in the Mulcair phone bank one night. He quickly became a former organizer.

Nathan Cullen’s sunny disposition and unflappable performance in debate won him early support, though his organization was knocked sideways by an incompetent manager in its first two months. He was replaced by Jamey Heath, a former Layton staffer, who dreamed up the novel gimmick of calling for joint nomination meetings to choose a slate of non-Conservative candidates for 2015. It won a great deal of attention — and derision. It would probably not have passed a legal test under the Canada Elections Act and was in any event offensive to many hardcore New Democrats, but it gave the Cullen campaign oxygen throughout the campaign, as the media were fascinated and intrigued by it.

The Paul Dewar campaign will be remembered as the last ever to be staged by a candidate incapable of addressing all Canadians in their own official language. It was a presumption that putative candidate Robert Chisholm wisely recognized was unsustainable, and he bowed out early. Dewar, who spoke what Ed Broadbent called “worse than Oshawa French— taking a shot at his own challenges with bilingual communication — humiliated himself each time he attempted to move off grade school phrases in debate.

Brian Topp cruelly highlighted Dewar’s incapacity in the Montreal debate with a question on Quebec cultural industries that had the mostly unilingual contender clearly baffled. He delivered an incomprehensible answer featuring “layzards.” Atypically gentle Quebec pundits explained that it was his version of “the arts,” not “reptiles,” in French. His powerful connections to the Manitoba New Democratic leadership and his energetic young campaign team befuddled the media into thinking that he was a contender until the final weeks. He never was.

Peggy Nash was the most obvious alternative to Mulcair for party loyalists worried about Mulcair as an outsider for leader and nervous about Topp’s lack of a seat or an electoral record. She was the heir to the labour movement-leader throne in the NDP, despite her life as a senior Canadian Auto Worker union staffer. Her mixed electoral record — elected twice, defeated twice — was rarely held against her by the media or her opponents, even when she inflated her three years as an MP into an improbable qualification as prime minister.

Media observers, perennially incompetent in covering leadership races as outsiders spun by people speaking in a code they cannot crack, regularly reported that Nash had big labour behind her, unaware that much of big labour would endorse Stephen Harper over someone supported by the iconoclastic auto workers union. Nash organizers were regularly smacked by the sardonic question, “So when Peggy sat in the office next to Buzz Hargrove for five years while he regularly sabotaged Jack Layton, was it because she was so irrelevant that he didn’t listen to her protests, or did she agree with his treachery?”

It was the Topp campaign that confounded the media most. Its presumption was initially celebrated and then derided, its endorsement strategy hailed initially as brilliant and later as dumb. A deep mid-campaign slump allowed other campaigns to point fingers at the foolishness of his having been instantly dubbed the front-runner. The Dewar campaign even claimed it had research that proved Topp was in fifth place, which was in fact its candidate’s ultimate first-ballot status.

The Topp campaign was presumptuous. It was the product of two stunning and deflating realities in the tumultuous weeks that followed May 2: first, the wide but unspoken recognition that Layton was not happy about Mulcair as his successor; second, it was not obvious that any of his caucus colleagues could stop him. In those moments, when the establishment in any party is very worried about succession, its members reach outside to cultivate a non-caucus candidate. It is always a high-risk, fraught venture.

Pop historians forget that Pierre Trudeau had nearly three years in cabinet before his “instant” elevation to stardom. More audacious and less well-prepared efforts to move an unelected outsider to leadership in the Ontario and federal Conservative parties failed badly. That Topp was able to push every other MP off the ballot before losing to Muclair on the final ballot needs to be seen in that light. It was always going to be a very long shot.

His campaign struggled with three attacks: no seat, no elected experience, and too many homes. The was probably resolvable only by having a sitting MP say he or she was willing to step down in advance, a risky and potentially dangerous gambit as it would have drawn serious fire from other camps and demands from the Tories that the sacrificial lamb step down immediately, potentially triggering a second by-election for the party, already fighting to defend Layton’s Toronto riding. Party organizers, among many others, would have seen it as ambition trumping responsibility. The campaign debated and then dropped the idea, despite prospective volunteers offering themselves for the role.

Some insiders, and the entire professoriat of Hy’s restaurant, argued that he should simply announce he was running in the by-election for Layton’s seat of Toronto-Danforth. Those more knowledgeable about the bitter realities of party clans and of the jealously guarded prerogatives of ridings knew better. First, the other leadership campaigns began to recruit their own Danforth candidates to force a heated nomination battle; then, the riding announced that it would seek and then vet its own slate of prospective candidates — and, of course, any of the leadership candidates would be invited to compete”; meanwhile, two of the Toronto NDP family clans were divided on whether to use their muscle to force Topp’s selection. In the absence of such clan leaders’ putative vetoes against other pretenders, it would have been a dangerous enterprise. Finally, George Smitherman, the retired Liberal Party organizational giant, was loudly rumouring several prospective star candidates for the red team. Again, after long discussion, the campaign decided it needed to move on. It did not develop an adequate explanation for its decisions, nor an effective counter to the “no seat, can’t be a leader” claims, which all the opposing camps used right up to convention day.

Having never been elected was not an issue until it became a surrogate for candidate performance. Topp started well, in press conferences, town halls and the opening debate. He then sagged badly, most painfully in front of supporters in Vancouver in December. It was a vindication of the claim that there is a difference between being a manager and being a candidate. Topp was exhausted and sick and had allowed himself to be badly handled on the road. It showed. His fight back from a couple of disastrous performances allowed the other camps to re-ignite the “no experience, can’t cut it” message.

His experience across Canada, having worked in four provinces in government and in politics, was a huge advantage in building his organization. His strength in British Columbia, for example, came significantly from his work on behalf of the BC NDP and on the election, only months before, of Adrian Dix as party leader. The disadvantage was that Topp’s political home was both everywhere and nowhere. He could claim credentials in all of Quebec, Saskatchewan, Ontario and BC, but he was the anointed son of none. The campaign chose to magnify his Quebec credentials. Some have derided this as a triumph of emotion over judgment, offering Topp’s weakest flank to his greatest enemy.

It is true that Topp, his campaign manager, Raymond Guardia, and many of his Quebec supporters were furious at Mulcair’s claim that Quebec voters had cast their ballots for him, and not for Jack Layton, on May 2. They ground their teeth at his frequent boast of how many caucus members he had recruited, helped build campaigns for and subsequently elected. The truth is that he had insisted, until the final days of the federal election, that some of the subsequently elected MPs work in Outremont on his campaign — demanding they not waste time on their own impossible prospects.

Still, Topp failed to adequately answer why he was anything other than the second-best choice for a Quebec leader — a view that the Quebec French-language pundits hammered relentlessly.

Among the media’s many misperceptions of the tribal tom-toms was the characterization of Topp and also of Nash as movement New Democrats resisting any effort to broaden their political tent. The mirror folly was that of Mulcair being seen by the punditocracy as a likely partner for defecting Liberals. Topp was the only one among the candidates to have helped manage a coalition with the Liberals in Saskatchewan and the only one to have negotiated with the federal Liberals about doing it again in Ottawa, in the ill-fated opposition coalition of 2008. Liberals in Ontario and Quebec, as well as in Ottawa, detest the new NDP leader, not only because he is a defector, but also because he was a consistent critic of Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty, Prime Minister Paul Martin and Stéphane Dion while he was a Quebec cabinet minister — and had been relentless in attacking them after his conversion.

Neither man would acknowledge it, then or now, but there is probably little light between where Topp and Mulcair would take the NDP as it continues its path to power. Topp knows how to manage the labour movement in politics; Mulcair does not. Mulcair knows how to persuade many that the sky is black, before conceding it is grey, without appearing to flip-flop; Topp is not as persuasive.

A key difference between them is their approach to the process of moving the party along its trajectory to power. No lifelong party activist would ever insult its veterans or traditions by mocking the party’s lack of “modernization.” Layton moved the party away from orthodoxy on Israel, on the environment, on taxation and on managing the public purse carefully and quietly, always paying respectful reverence to the party’s ancient totems. Topp was his constant counsellor in that subtle process.

Mulcair’s rhetorical fixation on sausage-making is galling both to true traditionalists and to Laytonites. They believe with considerable justification that a quiet project of modernization is precisely what they have devoted the past decade to and that its success was the basis of the party’s incredible rebirth. Political modernization is a product you deliver, not one you brag about.

Tony Blair modernized the British Labour Party, at the expense of its relevance and passion, say his critics, but he did it by producing and then displaying the changes he had fought for. Stephen Harper modernized some of the more dusty and recondite aspects of Canadian conservatism with stealth. Apart from Manning Institute moaners, most party activists are quite happy with their shiny new toy.

“Modernizing” the party’s comfortable opposition to the oil sands, for example, is doomed to failure if it is framed in those terms. For true believers, modernity is not the issue when it comes to resource extraction and environmental destruction. Their opposition may be premodern, but that ancient and eternal defence of the earth against its violators is precisely its strength and its appeal to the most hard-headed.

Rather than proclaiming the launch of a “new modernization campaign— the very phrase almost sounds like a Chinese National People’s Congress declaration — one way to reform of the party’s stance on the oil sands, for example, would be a statement of what is, what is possible and what a map of the road forward could look like.

So: the oil sands — not the tar sands, Tom — are being and will be mined. That is not negotiable and is, in any event, the position of the Saskatchewan NDP in and out of office. And: smarter leaders in the industry and in government know they need to clean up the garbage heaps of toxic waste that its oldest production sites continue to create daily — and they know they must make clear how much more sustainable current and future production processes are; they will be shut out of markets around the world if they don’t. Therefore, a community of interest among producers, regulators, solutions-focused NGOs, First Nations leaders and politicians does exist; now: find a way to unite them and to set those new rules and boundaries. The BC forest industry did it a decade ago. There is no reason why the NDP could not be a leader in such a dialogue, helping to frame a consensus. Just don’t call it modernization.

Neither man would acknowledge it, then or now, but there is probably little light between where Topp and Mulcair would take the NDP as it continues its path to power. Topp knows how to manage the labour movement in politics; Mulcair does not. Mulcair knows how to persuade many that the sky is black, before conceding it is grey, without appearing to flip-flop; Topp is not as persuasive.

Lyndon Johnson — as his biographer Robert Caro makes clear in the majestic five-volume political biography of the century (the fourth of five volumes was published in May) — was a statesman of astonishing achievement. He was also for much of his early life a sleazy and unpleasant man. Similarly, Richard Nixon has much more to lay claim to in achievement than Watergate. Yet he, too, got started in political life as a slanderer and a cheat. The alignment between political success and personal values is neither perfect nor constant.

Johnson was the subject of nearly 10 years of research by Caro and his wife, just for the first volume of their lifelong project. Not many of us would come out shining if subject to such scrutiny. Mulcair will now have to endure probing interviews with his many siblings, school chums and the long list of alliesbecome-enemies, as several authors compete to do the first tell-all biography of the man who could be prime minister in less than four years.

Johnson and Canadian leaders with enormous legislative leaps forward to their credit — Trudeau and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Mulroney and free trade — knew the transcendent power of loyalty in moving allies to take risks on their behalf. They knew that political hurdles leapt are the product of a hundred small graces conferred. So far, Mulcair has passed through most chapters of his political life with an angry posse behind him. Barring a sincere effort at healing, the response of the government of Quebec to any Mulcair request, if it is led by Jean Charest or for that matter any visible Liberal successor, will be curt, hostile rejection in public and derisory laughter in private.

He will fare worse with any PQ-led government, having taken his role as a political bruiser far beyond the bounds of acceptable discourse, several times libelling a senior PQ cabinet minister, in terms he knew — or should have known — were a lie. That he was guilty was established in a stinging judgment by a senior Quebec court that imposed a fine and costs of a quarter of a million dollars. The Quebec Liberal Party paid the entire bill.

None of this might matter if the Leader of the Opposition were to work out his thankless three years of hammering away at an entrenched government, only to be defeated and retire. Canadians would dispatch him from collective memory with the same sense of relief and quiet dismissal as they did Kim Campbell and Michael Ignatieff, flawed political posers who were not ready for the national stage. However, it is more likely that Mulcair will be in a position of enormous power come the Parliament elected in 2015.

At a minimum it seems likely that he will hold the balance of power in another Conservative minority government. In ascending degrees of risk or likelihood, it is also possible that he will lead a minority government. He may attempt to form a coalition government or beg key individual MPs to join his government to ensure its survival. Each of these challenges requires an ability to build coalitions of trust among skeptical partners. Each will succeed or fail on the ability of his partners to be confident that they will not be knifed at the first sign of disagreement.

Politics, like religion or professional sports, is partly built on redemption. Last year’s bum goalie is this year’s hero. Last election’s hapless defeated opposition leader is next election’s triumphant victor. Successful redemption involves two essentials, however: a willingness to learn and to change behaviour, and a conviction on the part of observers about the sinner’s newfound sincerity.

The next few weeks will reveal whether Mulcair’s new mantle of power has elevated his approach to politics, whether his appointment of former opponent Libby Davies as his deputy was a cynical public gesture or a genuine expression of the importance of healing. So far, the jury in the other leadership camps — all of whom studiously refused until the convention’s final vote to endorse Mulcair —remains out.

Externally, Canadians will begin to judge whether Mulcair is still merely the political equivalent of the hockey thug, the crusher whom circumstance has catapulted to team captain, or whether he has learned that higher office demands fewer low blows.

There are good reasons to be optimistic; Mulcair is a smart and seasoned political veteran. Though he has not shown consistent observation of political rules, he does know them.

He knows that if Rae and he waste too much political capital on each other, the winner will be the Conservatives. He knows that he may need both soft Quebec péquiste voters and persuadable Ontario Liberals if he is to come out on top. He knows that the media are keen to follow their inevitable cycle of attacking a former favourite at the first opportunity. And he knows that Canadians are squeamish about attack politics, especially from their leaders.

The Harper deviations notwithstanding, Canadian politics operates on a higher plane than does American politics, and the gap is widening. Canadian voters do not encourage Gingrich-style hysterical rhetoric. Outrageous attacks on the personal morality of one’s opponents are not a reliable path to victory with Canadian voters. One might hope that Mulcair’s bitter experience with Canadian libel law was a learning experience.

New Democrats, especially, are deeply offended by slash-and-burn political attack — it’s what makes them poor scandalmongers most of the time. They don’t have the stomach for the daily rehash of nasty insult and innuendo. They won’t put up with it from their leader — or about their leader.

However, neither will they tolerate regular embarrassment or humiliation at the hands of a misbehaving leader if they have not developed a deep emotional connection to him. New Democrats have been famously patient with leaders who make mistakes, who needed to learn on the job. Ed Broadbent was granted years of clangers and missteps before developing into a political all-star.

It used to be true of each of the national parties that leadership was a relationship of deep affection, pride and unconditional loyalty between activists and the man in the chair. Mackenzie King was not loved, admittedly, but Laurier, St-Laurent and Trudeau were. There will not be many tears shed at Stephen Harper’s retirement tribute night, but the fervent loyalty to Sir John A., Borden, Dief and Mulroney gave them the ability to weather otherwise impossible political storms.

New Democrats still respect and want to retain that tribal fealty to the leader. As a child I watched the tough internal opponents of Tommy Douglas weep openly at his defeat in 1965, as did the detractors of David Lewis a few years later. Bill Blaikie’s elegant and moving tribute at this convention to Jack Layton, the man who ended his leadership ambitions less than a decade earlier, evoked an outpouring of grief among men and women not given to such public displays. New Democrats want to be — demand to be — proud of their leader. It is what helps them endure the many defeats and sneering jibes from the media.

When you are the beneficiary of that unconditional trust and commitment you can move the party to places it believed that it did not want to go. Mulcair more than any leader before him will depend on the cultivation of such ties. If he uses the next three years to demonstrate commitment and compassion and conviction about the party’s traditions and history; if he remembers the birthdays and graduations and funerals of those far off-stage with sincerity; if he behaves with the same discipline and serenity in private that he displayed during this leadership race in public — then he can build a powerful army.

He may, indeed, deliver the first national social democratic government in North American history. This is the fateful gamble that normally cautious New Democrats made in Toronto on March 24. Given that the government of Canada may be in play, let us hope they bet wisely.

Photo: Worldstock/Shutterstock