Budget-making is never simple, but in the immediate postbudget punditry its complexity is often lost. Good fiscal planning deals with the today and the beyond; it attempts to balance shorter-term fiscal stability with longer-term fiscal sustainability, austerity and credibility, economic renewal and public expectations. Budget 2012 is a good example of such longer-term fiscal planning.

Consider, for a moment, the conceptual framework for fiscal planning. It starts with a hard-nosed analysis of the fiscal context, and today that context is global, it is no longer just Canadian or North American. It is concerned with fiscal credibility, which is hard to earn, and harder still to re-earn once lost. It focuses on fiscal stability, because balancing the books over the short to medium terms anchors so much else. It looks further ahead to fiscal sustainability, because balancing the books over the longer term must take into consideration trends in productivity growth, demographics and entitlements, not just the ups and downs of the economic cycle. It is concerned with coordination of policy, so that the left and right hands of macroeconomic policy — monetary and fiscal — are aligned, that Canadian policy is consistent with G20 policy objectives, and that federal and provincial fiscal policies are also synchronized to the maximum extent possible. It considers ways to enhance potential growth in the Canadian economy, thereby reinforcing fiscal sustainability, increasing competitiveness and improving our living standards.

The starting point for analyzing the 2012 budget is the fiscal context, and what a global fiscal context it is.

Structural trends and seismic events are reshaping economies, societies, politics, power and expectations around the world. And this changing context is shifting the drivers of success for the Canadian economy. These pivotal trends and events include the following:

- Pervasive globalization: The global centre of economic gravity is shifting toward Asia, with the rise of dynamic emerging economies in Asia and elsewhere. The “new global reality” is increasingly a two-speed world, and the West is in the slower lane.

- New global competitiveness: Increasingly productivity and innovation are driving competitiveness in advanced economies rather than low costs and massive scale; it is more about flexibility and creativity than geography and history.

- Demographics: For the first time in a very long time, the population is aging in Western countries, and the consequences of this are underestimated. Population aging will affect economic growth through slowing expansions in the labour force, and it will also affect longer-term fiscal frameworks through increasing pension and health care costs. One result is that the hunt for talent is going global, and the winners — countries and firms — will be in the driver’s seat in the new global competitiveness.

- Information revolution: From the Internet to Facebook to Tahrir Square, we have moved from a connected West to a hyperconnected world. This hyperconnected world is changing the reality of what a market is, how markets are accessed, where work can be done in real-time distributed systems and why the mantra of the hyperconnected global corporation is becoming “Imagined here, designed there, manufactured elsewhere, sold everywhere.” It is also redefining the nature of communications, both the medium and the style of messaging.

- The ultimate hangover: The global financial crisis of 2008 is like the hangover that will never end, no matter how many aspirins governments and financial systems in many countries take. It has spawned a low-growth, low-interest-rates, high-volatility environment in the developed world; continued deleveraging and uncertainty are facts of life in Europe and the lingering reality in the United States.

The budget characterizes the current global economic environment as still highly uncertain, with the key risks emanating from the European sovereign debt and banking crisis. While the United States economy is seen as showing signs of renewed momentum, this has to be contextualized against the large employment and output declines suffered during the recession, and ongoing household deleveraging and housing sector weaknesses in many parts of the country. In the emerging economies, growth has slowed due to weakness in OECD economies but it remains robust, particularly in China.

Among the G7 countries, Canada’s performance during the recession and recovery has been quite solid; its real GDP is more than 3 percent above its prerecession peak, while those of the US and Germany are less than 1 percent above prerecession levels, and those of the rest of the G7 countries have yet to recover past output peaks.

The global financial crisis of 2008 is like the hangover that will never end, no matter how many aspirins governments and financial systems in many countries take. It has spawned a lowgrowth, low-interest-rates, high-volatility environment in the developed world; continued deleveraging and uncertainty are facts of life in Europe and the lingering reality in the United States.

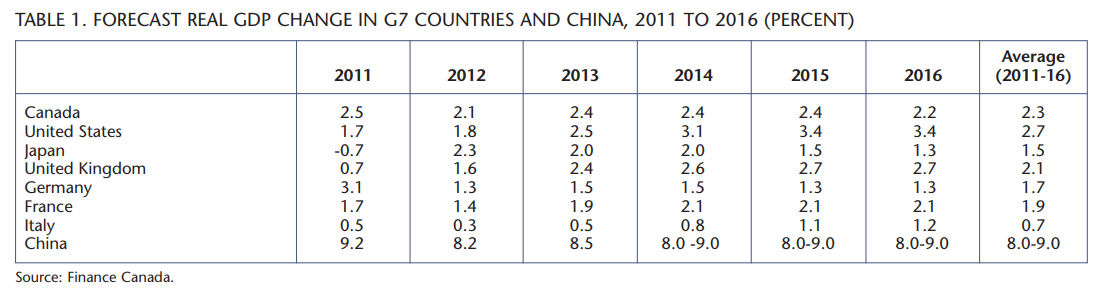

Table 1 presents the underlying budget forecasts for future real GDP growth across the G7 countries over the 2011 to 2016 period. Several aspects are worth noting. The two-speed world is quite evident from these forecasts: the average real growth of the G7 economies is less than 2 percent over this six-year period, while real growth in the dynamic emerging economies, led by China’s, is expected to be 6 percent or more. The euro-zone economies will lag the rest of the advanced countries as the lingering impacts of the debt crisis and the emerging impacts of aging demographics and unsustainable entitlement programs take their toll on potential growth.

Canada is forecast to do relatively well, and the neighbourhood even better, compared to the G7 average. The challenge is that the 2.3 percent average pace of Canadian growth forecast over the 2011 to 2016 period is low relative to what it was in previous postwar cycles, reflecting slow productivity and labour force growth, and continuing softness in our major export markets, which are predominantly G7 countries.

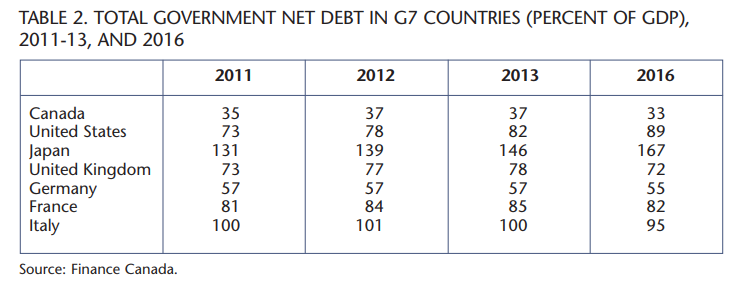

In today’s volatile and uncertain international environment, how should we feel about Canada’s fiscal credibility, which was gradually lost over the 1980s and early 1990s and re-earned by dramatic, tough and long-lasting fiscal actions in the mid-1990s? As stands out in table 2, in 2012 Canada has the lowest total government net debt as a percentage of GDP among the G7 countries, less than half that of that of the United States and well below that of Germany, which is the second-best fiscal performer in the G7. Canada’s Budget 2012, with its substantial fiscal restraint measures, should only reinforce the confidence in markets that the government will achieve its previously stated objective of returning to fiscal balance in 2015/16. Considering current fiscal plans across the G7 countries, which have varying degrees of uncertainty, particularly in the United States, Canada will have the strongest total government fiscal position by far in 2016.

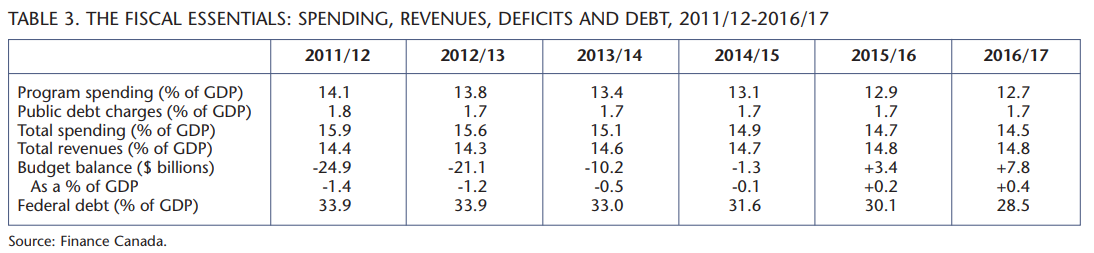

Between 2007/08, the last year the federal government was in surplus before the global financial crisis and recession, and 2015/16, when the government expects to return to fiscal balance, federal debt will have risen by roughly $150 billion. This will raise public debt servicing costs on an ongoing basis and increase the interest rate sensitivity of the federal fiscal framework. Nevertheless, federal net debt as a percentage of the economy is forecast to decline from today’s level of 33.9 percent to 28.5 percent in 2015/16, which is below prerecession levels.

Provincial debt levels have also increased significantly since the global financial crisis and recession, and fiscal deficits remain large in several provinces. They have now announced plans to return to more sustainable fiscal positions, albeit more slowly than the federal government. The federal government also announced in Budget 2012 the results of the triennial review of the Canada Pension Plan (CPP); this confirmed the sustainability of the CPP for at least the next 75 years at current contribution rates and demographics, something that few other G7 countries have put in place.

The 2012 budget takes aim at medium-term fiscal stability with a series of spending reduction measures totalling about $5 billion, or 0.2 percent of GDP when fully implemented. There are also several revenue enhancement measures that add up to $1 billion over the same period. The result, as the fiscal essentials set out in table 3 indicate, is a credible fiscal plan to balance the books by 2015/16 at the latest, and likely earlier given the degree of prudence built into the fiscal framework. The federal deficit this fiscal year is estimated at $21.1 billion, or 1.2 percent of GDP, falling to a deficit of $10 billion next year. This will allow the federal government to have a declining federal net debt-to-GDP ratio starting next year, a declining total government-spending-to-GDP ratio throughout the fiscal plan and stable total revenues-to-GDP ratio.

The 2012 budget makes a credible start at longer-term fiscal sustainability, although this will likely take several budgets to fully tackle and sustained efforts on the economic renewal front. The fiscal sustainability dilemma is posed by declining productivity growth and aging demographics. Indeed, with both productivity growth and labour force growth now under 1 percent, sustainable Canadian real growth will decline to the 2 percent range from around 3 percent over the last quarter century absent ongoing favourable terms-of-trade shifts.

This will produce the double fiscal wallop of lower revenue growth than we’ve experienced for decades and higher spending pressures on health, pensions and other demographically related spending. Squaring the circle of sustainable fiscal balance comes back to increasing innovation and productivity performance to rebuild our sustainable potential growth and adjusting our entitlement programs to the growth economy we have. Ultimately, fiscal balance and economic growth must go hand in hand.

In introducing upward adjustments to pension eligibility to 67 from 65, putting a cap on health transfers in line with nominal income growth and making changes to balance equally employee and employer contributions to public sector pensions, the government has begun the task of establishing fiscal sustainability in the longer-term fiscal framework for an environment of aging demographics and slowing productivity growth. It is a task that the federal and provincial governments will need to return to in subsequent budgets.

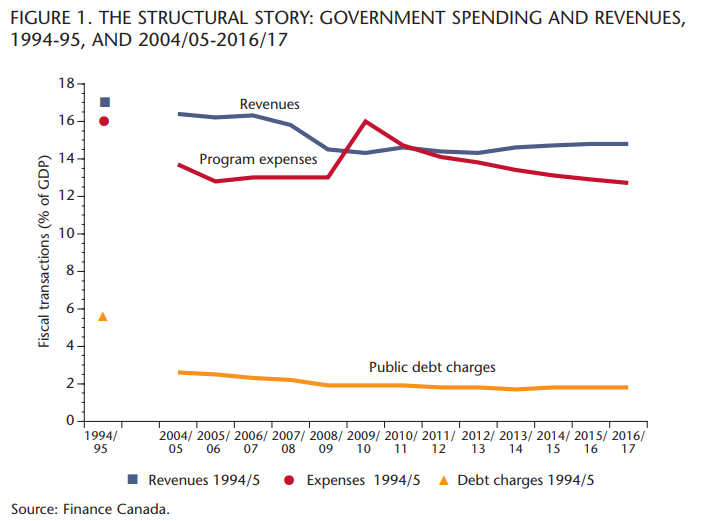

By 2015, when the deficit is forecast to be eliminated (as figure 1 indicates), federal program spending as a proportion of the economy is estimated to return to prerecession levels (which are well below the levels that prevailed in Canada prior to the seminal fiscal corrections of the mid-1990s) while revenues as a proportion of the economy are forecast to remain below prior levels. This suggests room exists to raise revenues for fiscal sustainability through more aggressive tackling of tax expenditures in subsequent budgets.

Clearly an important part of ensuring long-term fiscal sustainability is enhancing potential growth. And here, Budget 2012 showed leadership on a number of fronts. The budget responded to the following inescapable facts: market diversification for our exports and investment capital was needed in the face of the economic gravity shift to Asia; poor productivity and innovation performance was undermining Canadian competitiveness, particularly in the absence of a low Canadian dollar; the natural resources sector, particularly energy, was a source of Canadian advantage but only if it could reach markets in a timely and efficient manner; and attracting skilled immigrants to Canada was crucial given our aging demographics.

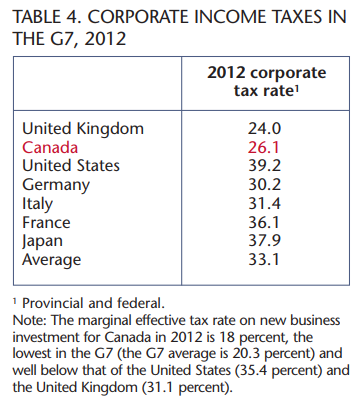

The budget’s response was targeted in six areas: (1) leadership and renewed support for innovation, with an explicit recognition that it is the private sector that must be more innovative; (2) trade enhancement through new trade negotiations and a promised overhaul of the trade commerce strategy; (3) more efficient regulatory processes for natural resource developments; (4) more efficient processes for immigration; (5) reaffirmation of the importance of foreign investment and implicit acknowledgement that it is less the ownership of capital than the behaviour of capital in Canada that will drive benefits for Canadians that matters; and (6) confirmation of the size of the G7 corporate income tax advantage (see table 4) that Canada has created over the last decade, especially in relation to the United States.

Significant economic renewal in the Canadian economy over the longer term, which is needed to increase our sustainable growth potential, will necessitate an ongoing focus, further deepening and diligent followthrough in these targeted areas in subsequent budgets. It will also require policy coordination with provincial governments and collaboration with the private sector and universities. More productive government will help improve productivity throughout the Canadian economy.

In today’s changing global environment, longer-term planning is essential. The 2012 budget appropriately returns to a balance between short-term exigencies and longerterm structural challenges. The budget’s five-year fiscal plan takes Canada to the eve of its 150th birthday. For Canada to realize its potential going forward, we must have innovative policy strategies with flawless execution; we have to be creative and flexible, not rigid and rule-bound; we must be early adapters, not late followers; and we need to compete to win, not play defence.

Photo: Shutterstock