As Canadian producers nervously await the outcome of softwood lumber talks with the US, the stakes are especially high for one Indigenous-owned sawmill in Saskatchewan’s northern boreal forest. NorSask Forest Products in Meadow Lake sees about 60 percent of its production going to the US. It is part of a growing Indigenous small business sector that tends to export at a higher rate than other small Canadian firms, according to a recent report by TD Economics.

However, freshly imposed American trade sanctions could pull NorSask under, warns Al Balisky, president and CEO of Meadow Lake Tribal Council Industrial Investments (MLTCII). The tribal council owns the operation. “We are a single stand-alone sawmill doing our very best to survive in a tough environment,” says Balisky.

MLTCII is lobbying for special protection for itself and all other Indigenous lumber producers. And it has the backing of the National Aboriginal Forestry Association.

An American company built the mill in 1971. In 1988 an employee group along with the local tribal council and a western Canadian company took over the mill. Ten years later, the tribal council bought out its partners.

“The Meadow Lake business arm was very progressive in getting into the forest business. They are one of the leaders in the country,” says Sean Willy, incoming president and CEO of Des Nedhe Development, the investment arm of English River First Nation in Saskatchewan. English River is a shareholder in the Meadow Lake Tribal Council’s economic development corporation, and thus an indirect shareholder in NorSask.

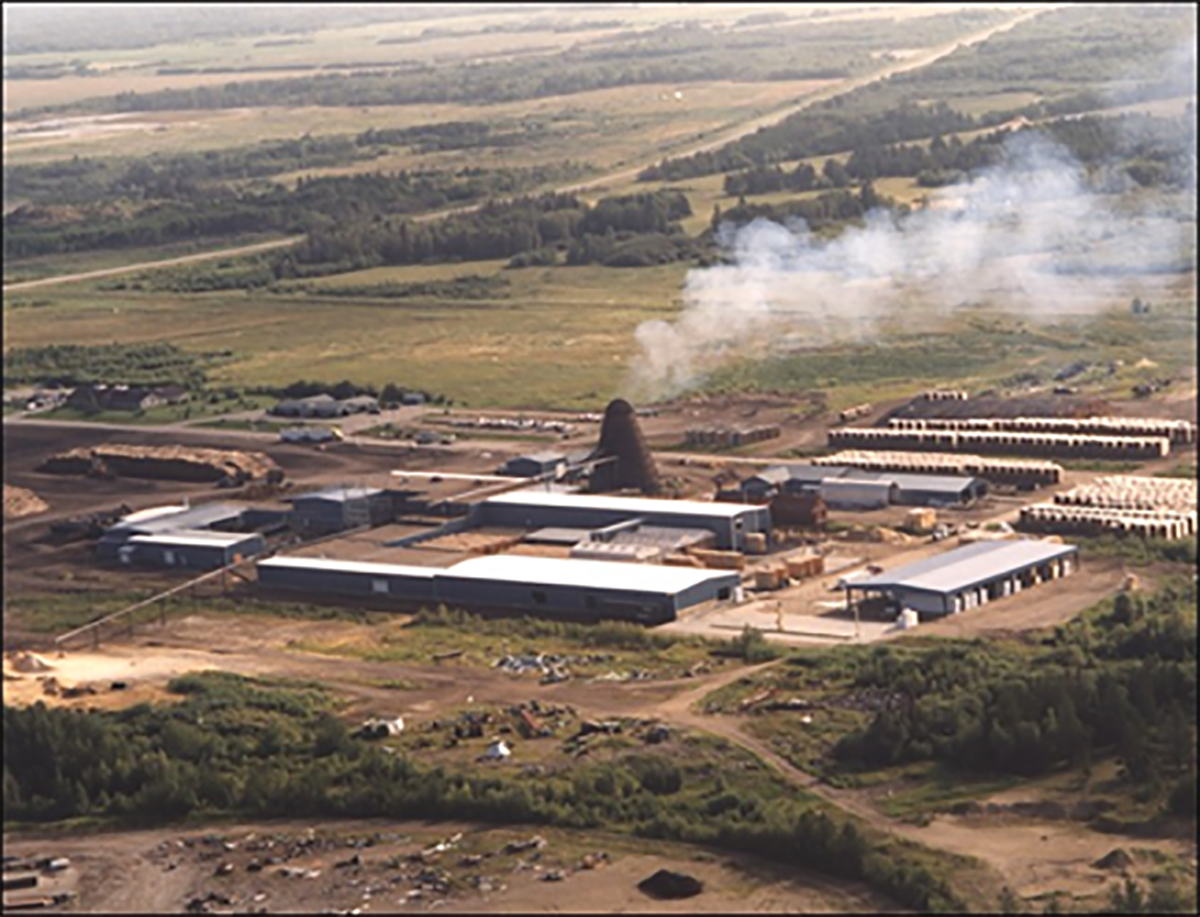

The NorSask mill is now described as the only completely Indigenous-owned major softwood lumber producer in Canada, with significant exports to the US. With annual revenues of $40 million, it employs about 100 full-time mill workers producing 120 million board feet of lumber each year, enough to frame more than 12,000 2,000-square-foot homes.

NorSask got to that position with no special help from government, Balisky says. Yet in the Canadian industry as a whole, it would be classified as a small to medium-sized player — with significant disadvantages.

For one, it produces only lumber, while other companies can generate cash flow by diversifying their product offering to include pulp and oriented strand board. Nor has NorSask bought up American sawmills, as some other companies have done to shield themselves from American trade action. Another disadvantage is that it is located in the middle of the continent, with no rail access, so prospects are poor to expand its market beyond the American Midwest.

Many sawmills across Canada shut down during the major downturn in the US housing market. But NorSask pulled through, albeit with curtailed production, slowly making its way back during the subsequent market uptick. The weakened Canadian dollar of recent years has also helped. However, those years of struggle left NorSask in a compromised financial position, Balisky says. Renewed countervailing and anti-dumping duties come at a particularly bad time.

NorSask is pushing the federal government to negotiate a tariff-free export quota reserved for Indigenous producers, with room to grow from the current trade volume. NorSask itself wants to push its US exports to 70 percent of production, from the current 60 percent.

Balisky says the quota would simply be a matter of Ottawa living up to its commitments and obligations under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which says, “States shall take effective measures and, where appropriate, special measures to ensure continuing improvement of [Indigenous peoples’] economic and social conditions.” As well, Balisky says Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s call for “a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples” should include support and advancement of Indigenous economic development.

Willy is encouraged to see some federal government action in this area: steps such as including Indigenous business in trade agreement discussions, bringing Indigenous leaders and businesses along on trade missions and funding foreign offices and market studies. The recent Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement signed with the European Union gives the federal government the right to exercise a preference for Indigenous suppliers in procurement.

Willy, who is also co-chair of the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, would like to see all levels of government set targets for the percentage of goods and services they procure from Indigenous firms, in a “buy Indigenous” policy.

“If you do that then naturally… communities will go on this journey to grow their businesses outside of this country,” he says.

This article is part of the Trade Policy for Uncertain Times special feature.

Photo: Shutterstock/Guy J. Sagi

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.