Canada’s agri-food sector is a national strategic asset. It encompasses much of the country’s vast natural resource base and makes a substantial contribution to the economy. The sector is a major global exporter and maintains a sizable positive trade balance thanks to its strong commodity exports. It is a major employer — providing jobs for one in eight Canadians. The agri-food sector provides a significant proportion of the food we eat every day and is directly linked to the health and well-being of Canadians. Our country produces safe, high-quality food.

Successful in so many respects, the sector should only gain in significance as global demand for food, feed, biofuels and biofibres increases. But it also faces considerable challenges.

First, a number of worrisome trends are emerging related to producer profitability and the viability of the processing sector (Canada’s rank in processed food exports has fallen from third to seventh). Canada’s overall global export ranking has dropped from third to fourth — we’ve been surpassed by Brazil, and China and Argentina are close on our heels. These countries are making inroads, in part, thanks to their strategic advantage as low-cost commodity suppliers.

Second, human health issues are increasingly prevalent, given the mounting incidence of diet-related diseases. This is a crisis: Canada currently faces an obesity epidemic (as do other countries). The related cost and health burdens are rising, perhaps unsustainable. Indeed, forecasters see health care costs consuming some 70 percent of provincial budgets as early as 2017, and Canada’s total health expenditures already exceed $190 billion annually. Diet and food play a big role in these developments; it is estimated that as much as 80 percent of premature heart disease, stroke and type-2 diabetes and 50 percent of cancer could be prevented through a healthy diet, as part of a healthy lifestyle.

Third, sustainability is a growing concern in the agri-food sector. The marketplace is increasingly focused on sustainability performance and a broad array of ethical food production practices. This is impacting global and domestic food supply chains. Retailers and consumers are changing their selling and purchasing practices. For instance, Loblaws is moving toward providing 100 percent cage-free eggs (President’s Choice brand) and toward selling only 100 percent sustainable seafood by the end of 2013. At the same time, adapting to the changing climate must also be a priority if we are to remain a reliable food supplier in the years ahead. This is especially critical given the need to feed a hungry world. By 2050 the global population is forecast to exceed 9 billion people and food demand is expected to rise 70 percent.

In this context, it is increasingly vital to identify a new, viable economic model, or models, to address these challenges and to position Canada’s agri-food sector for future prosperity. Clearly, we are at a crossroads.

In 2011, the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute (CAPI) released a report calling for a national agri-food plan and offering such a new framework. Canada’s Agri-Food Destination — A New Strategic Approach received significant nationwide media coverage and garnered considerable reaction from stakeholders and interested parties from across the country. It contains strategies for helping the sector move toward greater prosperity, enhanced population health and more sustainable ecosystems.

Above all, a new, more collaborative spirit both within the agri-food sector and among other sectors is needed. By working collaboratively, Canada’s agri-food players will maximize their ability to improve their productivity, differentiate their products and enhance their competitive positions in domestic and export markets. A more collaborative operating environment will enhance their competitiveness and provide broader health and environmental benefits to society at large.

Indeed, the agri-food sector can provide solutions that will help prevent disease and obesity. But in order to do this, we need to significantly change how the departments of agriculture, of health, of innovation and of education as well as the private sector and others work together. An evolutionary approach is insufficient. An agri-food plan for Canada must recognize the need for this convergence — and soon.

At the same time, the global marketplace is increasingly focused on how food is produced and whether food production is degrading ecosystems. Consumers here and abroad are raising the bar for how the agri-food industry responds to environmental challenges. Canada’s agri-food sector can provide solutions here, too. Its position as a reliable provider of safe, high-quality food can only become more important as the demands on the food supply and the scarcity of natural resources intensify. A plan must be developed that generates greater convergence with respect to how players and policies intersect in agriculture, biotechnology, environment, and trade and innovation, among other sectors. Climate change adaptation must be a central facet of this collaboration.

In fact, many governments and organizations, abroad and at home, are contemplating the connections between food production or supply viability and these broader societal issues.

For instance, the United Kingdom’s 2010 report Food 2030 states: “The long term sustainability of our food system is the central concern…A plentiful supply of healthy, safe and affordable food is essential for a good quality of life, and our ability to produce this food depends on the way we manage and maintain the natural systems that provide the essential inputs and services for our farms and fish stocks; clean water, fertile soil and pest control are all provided for free by healthy ecosystems.”

The World Economic Forum has declared that agriculture provides much more than food. Its New Vision for Agriculture seeks to harness the power of agriculture to advance goals for greater food security, environmental sustainability and economic opportunity. It aims to increase global food production by 20 percent, decrease emissions by 20 percent and reduce the prevalence of rural poverty by 20 percent every decade.

In the United States, a new nonpartisan initiative known as AGree has recently been established. It is supported by nine leading foundations, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Kellogg Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. It is looking at food-providing solutions across multiple sectors, including health, environment, energy and rural economies. AGree is based on the thinking that agriculture has evolved from simply producing food to feed people to being a sector that has numerous demands placed on it, including in areas of public health and economic growth.

In Canada, a broad number of organizations are linking the issues. The Metcalf Foundation’s report Menu 2020: Ten Good Food Ideas for Ontario acknowledged the links between food and how food can address a variety of social, cultural, environmental and economic problems. It seeks “solutions to a broken food system in which farmers find it challenging to make a living growing food, and consumers find it difficult to make the good food choices they want to make.”

The City of Toronto’s 2010 Food Connections Report sees food as a means to help cities meet a variety of goals based on a vision of a health-focused food system. “This new approach can create a healthier population, generate green jobs, build strong communities, protect the environment and empower people with food skills and information.”

The Conference Board of Canada is undertaking new work in this domain to address what it calls “one of the great mega-issues facing our country today.” It goes on to say, “Food impacts Canadians in an extraordinary range of ways: it affects our lives, our health, our jobs, and our economy.” The Canadian Federation of Agriculture is also developing a national food strategy to help “create a healthier, environmentally sound and more economically prosperous nation” while the federal government is exploring initiatives with systemwide implications, such as the concept of One Health, which recognizes the linkages among human, animal and ecosystem health. The Federal Sustainable Development Strategy has established targets and implementation strategies to provide a whole-of-government approach in order to achieve sustainability objectives across federal departments.

These initiatives signal some compelling common themes. First, they recognize that food and the agri-food sector have a vital purpose for the wellbeing of people and the planet. Second, they see food and other stakeholders — such as those in health and environment domains — as being intimately linked. Third, by pursuing common objectives, the very different stakeholders in the agri-food sector and other sectors will increase their chances of achieving win-win outcomes.

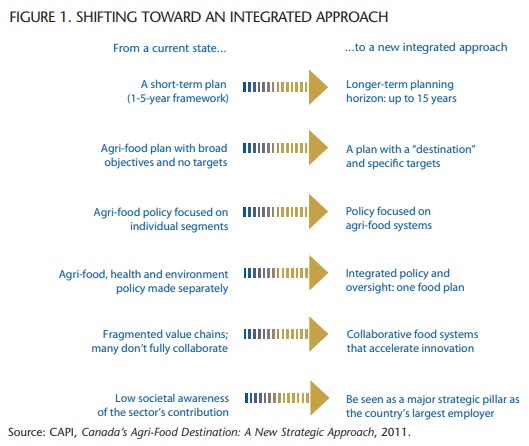

At the heart of the CAPI report is a new conceptual framework geared to helping the sector shift from its current state to such a new, more integrated approach (see figure 1).

Instead of crafting a new vision, the report made the case for establishing a “destination” — or a more specific objective. Simply put, it says, we need to have the most successful good food systems on the planet by 2025.

One of the main changes required is to stop talking only about supply chains, value chains and product lines, and start thinking more about agri-food systems.

The report calls for a long-term agri-food strategy that goes beyond the current five-year planning cycle. It advocates setting performance targets and metrics to spur action. The targets can be catalysts for change and dialogue. The report suggests that by 2025, Canada should strive to double agri-food exports to $75 billion per year, produce and supply 75 percent of its food from domestic sources and rely on biomaterials and biofuels in 75 percent of the sector.

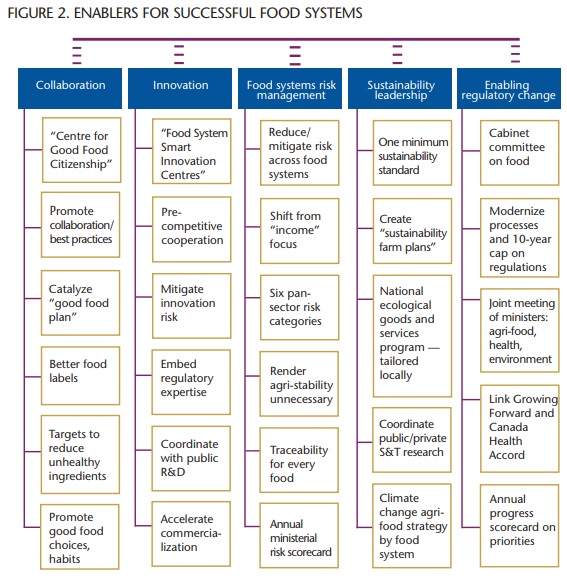

There are five drivers — or enablers — to help the agri-food sector move forward (figure 2). The enablers are based on changing the way the sector and other partners collaborate, innovate, manage risk across food systems, stimulate sustainability practices and support regulatory change.

One of the main changes required is to stop talking only about supply chains, value chains and product lines, and start thinking more about agri-food systems.

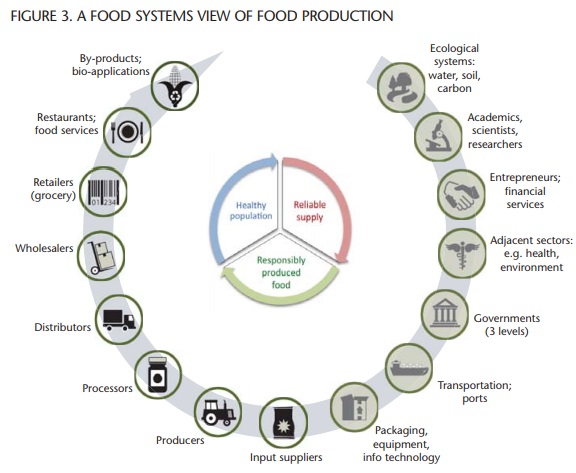

The traditional view of production chains is often expressed in a linear way and built around supply and value chains. Supply chains are typically considered within the context of how a single firm coordinates its activities with others in the chain, in order to deliver a given product at the lowest cost. Value chains are focused on identifying attributes desired by the consumer, creating value and then capturing the value for participants in the chain. In general, this view lacks fully integrated policies and falls short of optimizing collaboration between the major players in the agri-food sector and other stakeholders.

By contrast, the new approach suggests that supply and value chains can prove more successful if they are integrated into a food system (figure 3).

A food system is an operating environment for agri-food partners to meet consumer food demands and society’s expectations, and to do so by working collaboratively with a full range of partners. This approach requires a mindset shift. It is about changing the way the players work together, innovate and manage risks, and how government policies can support this change.

Food systems are not brought about solely by government action, although governments can certainly enable them. Within the context of a collaborative operating environment, food systems are created by players (that is, value chains) in a sector or region. They are industry-led. As such, the players recognize that they have a significant common interest in meeting consumers’ needs. By collaborating, they can create value for their operations as well as adding value for society. A food system typically includes a number of competing value chains.

The participants in a food system have common objectives. Food systems also acknowledge their impacts on food production, including environmental impacts. For example, the US dairy industry has set a target to reduce CO2 emissions by 25 percent by 2020. Initially undertaken to meet the sustainability expectations of a major retailer (a matter of market access), this initiative is reducing emissions across the whole dairy supply chain. It is also having other impacts that will improve the industry’s sustainability and productivity, such as creating R&D opportunities and reducing energy costs.

There are several examples in Canada that show how these connections can be further cultivated.

Municipalities have a significant role to play in food issues and agri-food policy. Often dismissed as small scale, the food systems in urban communities — where some 80 percent of Canadians reside — are vibrant. For example, Metro Vancouver’s more than 2,600 farmers account for some 28 percent of British Columbia’s gross farm receipts. The Golden Horseshoe area from Toronto to Niagara is developing a strategic plan for its broad food sector, which is estimated to generate over $12 billion in agricultural and food processing activity annually. Municipalities need to be connected to the broader policy framework.

Numerous food-health initiatives are under way; for example, programs to improve healthy food choices at schools and population health promotion campaigns aimed at reducing the consumption of unhealthy ingredients. While all of these initiatives have merit, they are typically led by governments or nongovernmental organizations. More work is needed to fully involve all agri-food players. As well, sharing best practices could generate insights for creating food innovations and help consumers make good food choices, but there is no systematic way to do this.

Connections are being forged between the health and agri-food sectors; for example, there is government funding to support clinical trials into flax, pulses and other commodities. By generating scientific evidence of the health attributes of these commodities, such research can be used to develop and differentiate products in the marketplace. The convergence of health and agriculture research is a powerful potential innovation driver. Yet the agri-food and health policy and research agendas have largely been designed separately. Still, change is afoot. Alberta recently launched a unique initiative involving its research and innovation system. It seeks to improve consumer health and well-being and increase the competitiveness of the province’s food and agricultural industries.

Perhaps the best known example of intensive collaboration is found in canola production. An entire industry has emerged because of public and private sector research efforts; the current focus is on producing a canola oil that does not require hydrogenation and is a zero-trans-fat product for the food industry. The demand for healthy oils by restaurants, processors and consumers created this market. Government and corporate research and investment supported this shift to healthy oils, although no doubt it was aided by the publicity against trans-fat among nutritionists, the media and population health experts, as well as the mandatory labelling of trans-fat levels.

A number of initiatives are underway that involve agri-food players and researchers working together to derive greater value. The Sundown pear is a new variety developed as a result of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research. It is the first made-in-Canada pear, designed for Canada’s climate and markets. The pear has been well received by consumers in test markets, and it has a three-month storability, which extends the marketing season.

The Vineland Research and Innovation Centre obtained global marketing and commercialization rights for the pear from AAFC. It concluded an agreement with the Vineland Growers Cooperative for the pear’s marketing in several provinces, the first production and harvesting agreement of its kind. The deal means that growers are given a new variety and a market together, rather than just getting “the tree” and the downstream risk of finding markets themselves, as has been the usual course. The cooperative already has well established working arrangements with major retailers, which have indicated interest in the new pear. Of further benefit, the centre is pursuing licensing agreements with production systems in other regions in Canada and abroad. Determining how we best replicate such successful approaches would have much merit.

The success of Canada’s agri-food sector depends on the participation of a wide array of stakeholders. Often, the connections are implicit, such as the requirement for transportation and seaport infrastructure in order to export the country’s commodities. But many other adjacent sectors are needed, such as those of health, environment and biotechnology. In working more collaboratively and developing a long-term plan, the agrifood sector can move toward fulfilling its tremendous potential and enhancing its position as a major national strategic asset. Taking a food systems approach is pivotal to fulfilling Canada’s potential to achieve greater prosperity, enhance population health and sustain ecosystems.

The stakes are enormous. What we do collectively to position Canada for change will have a profound impact on our economic future and our society’s well-being. Given that we are a major food exporter, this will have major implications well beyond our borders.

Photo: Shutterstock