An electoral system does not exist in a vacuum. It is part of an evolved and integrated set of institutional arrangements that together make up a larger and infinitely more complex political system. Collectively and with the passage of time, those institutional arrangements establish the framework within which public policy is formulated, political accountability is maintained, and public expectations about elections, parties and candidates are shaped. In consequence of those expectations, voters and parties make strategic electoral choices, parties and party systems take shape, and representative and governing institutions operate.

To call for the reform of the electoral system, to speculate about the presumed benefits that could be claimed to flow from a different electoral system, and to imagine how an altered method of voting would play out in Canada is one thing. But to do so without first considering the larger institutional context and the expectations that would be created under a different set of electoral rules is quite another. The standard maxim about well-intended reforms leading to unintended consequences should serve as a warning here. As Bert Rockman of the University of Pittsburgh reminded his American political science colleagues not long ago, “yesterday’s reform often is today’s problem.”

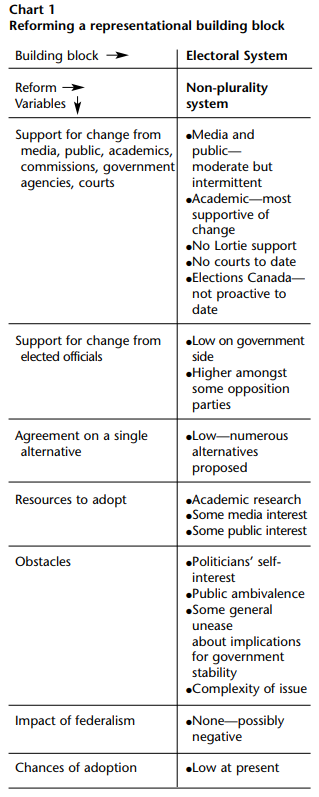

It is idle to speculate about reforming an electoral system (an instrument of government I define as an essential “representational building block” of a liberal democratic state) without first determining the conditions to be met before any changes can be adopted. If an electoral system is to be reformed, certain critical variables must first be in place. The purpose of this paper is twofold: to remind us of the institutional and constitutional framework within which any electoral system must operate in Canada and to describe briefly the conditions that must first be met before electoral reforms can be put in place in this country.

At their most basic levels, the parliamentary and federal systems together have served since Confederation as the essential institutional contexts within which parties have developed and electoral outcomes have been determined. Barring some major and unforeseen event, that will continue to be the case well into the future. Within those parliamentary and federal arrangements, the problems of plurality elections in Canada that are typically identified by observers for special comment derive from the degrees of “fairness” and “representativeness” of electoral outcomes for parties, voters and regions. Those terms cast a wide net. They range from concerns that are essentially representational, such as those expressed by Alan Cairns more than three decades ago about the tendency of our electoral system to produce sectionalized and potentially non-integrationist federal cabinets and parliamentary caucuses, to attacks on grounds of democratic theory about the perverted allocations of votes into seats that are seen as “unfair” to some regions, parties and voters.

Whatever alternative or modified electoral system may be agreed to in the years ahead, it must be one that is compatible with Canada’s larger parliamentary, federal and constitutional systems. On the governance side of the reform equation a different electoral method must ensure the continuation of certain fundamental cornerstones of our parliamentary system. This should hold true even if coalition governments of two or more parties become the governing norm as a consequence of electoral reform. What are Canada’s essential constitutional principles? At their most basic level they include cabinet secrecy and solidarity, Commons confidence votes on issues of critical public policy, responsible government and (however shop-worn this concept may have become) individual ministerial responsibility.

Regardless of the changes that may be made to the electoral system, these constitutional and parliamentary pillars of Canada’s political system should be neither fundamentally altered nor discarded in favour of some as yet untried and unfamiliar ones. Our constitutional-federal-parliamentary systems have deep roots in this country. Collectively they are the source of our entire machinery of government. They have contributed to and helped to shape our political culture, the expectations that the electorate holds about the political process and parliamentary government, and the internal organizational and authority structures of the parties. Too much is at stake both constitutionally and institutionally to contemplate changes to the electoral system that might compromise or endanger the carefully crafted set of arrangements we have established to govern ourselves. Thus, the fundamental principle that must be adhered to in the search for alternative methods of election is that whatever system is eventually settled upon must be compatible with our constitutional, federal, and parliamentary systems.

On the representational side, the range of considerations is no less important than on the governance side. Representational considerations are, in a sense, more complex than governance ones, or at least they have become so in the past two decades or so. The advent of identity politics, in which women, aboriginals, and ethno-cultural groups have made powerful representational claims, has the potential of making the issue of electoral reform a particularly salient one for many who now feel disadvantaged by plurality voting. So too has the move toward direct democracy helped to reshape representational practices. The appeal of such plebiscitary vehicles as referendums, recall, initiatives, and, in the case of national and provincial party organizations, universal membership votes, has been unmistakable. The creation first of the Reform then of the Alliance parties speaks to that issue.

Identity politics and direct democracy can be expected to impact negatively on the age-old accommodative model of Canadian parties if parties see a different electoral system as offering a different set of strategic options and if they choose to fashion their respective support bases around a narrow range of social, linguistic, racial or regionally-concentrated supporters. New institutional arrangements, we need scarcely remind ourselves, bring with them new incentives and strategic options. Should electoral changes come to pass this could mean the demise of transnational brokerage party model first crafted by Macdonald and Laurier. It is true that the broadly-based catch-all party has become an exception on the national political scene in the past few elections. But we need to be mindful of the possibility that its recent exceptionalism, which surely owed much to the peculiar workings of the plurality vote system at a time when the governing Conservative party essentially imploded over its constitutional initiatives and its perceived public policy slights of western Canada, could in fact get worse under a reformed electoral system.

Every electoral system offers its own set of incentives. For truly national parties intent on winning office under the plurality system the most obvious of these incentives has been to create and maintain the “big tent” within which inter-regional, linguistic and social differences could be accommodated. Whatever reforms are introduced to Canada’s electoral system should not encourage parties to abandon that option in order to pursue other more narrowly or sectorally-based ones that, in turn, would be destructive of the larger national political community in Canada. The leadership style favoured by Mackenzie King owed much to the incentives that first-past-the-post offered parties competing for electoral support. We should not set out to construct an electoral system that would all but rule out the continuation of that accommodative approach to national political leadership.

Representation has a practical as well as a theoretical base in our political system. Practical representational concerns of MPs will no doubt become part of the background discussion of any move to reform the electoral system. For example, for Canada to change its method of electing its members to, let us say the mixed-member proportional system of Germany or New Zealand, would require several fundamental institutional readjustments to be made that would in practical terms hold little appeal for many MPs. Principal among these would be the need to redraw electoral boundaries around substantially larger ridings. If only one half of the Commons were to continue to be elected from single-member constituencies, the size of the ridings from which they would be chosen would effectively double— both in population and territory. This would hardly be a selling point for electoral reform for members, candidates and party organizers who already complain of constituency workload and geographically over-large ridings.

Debate over electoral reform in Canada has been episodic. It has not followed a consistently upward-moving trend line growing in intensity from one election to the next. The issue has all but disappeared from public view when, as in 1968 and 1984, elections produced majority governments whose levels of popular support and parliamentary representation were not wildly incommensurate, the governing party enjoyed a measure of electoral and parliamentary support from all regions, and the opposition parties saw their shares of seats more or less reflect their shares of votes.

But interest in reforming the electoral system has re-ignited whenever, as has been the case most strikingly since 1993, popular votes were not converted into seats in a fair and reasonable manner, the regions sensed a heightened alienation from the centre and found comfort in singling out the plurality electoral system as a major contributor to that alienation, and the shares of Commons seats of several parties bore little relationship to their respective shares of popular votes. It is that stage of re-ignited debate that we are now in. Even so, the intensity of and interest in the current debate over plurality voting in Canada comes nowhere near matching that of the 1920s when the question of reforming the electoral system was first addressed on a major scale in Parliament and in many provincial legislatures.

This irregular nature of the debate over our electoral system is important to note, for it suggests that Canadians do not share a profound or deep-seated distrust of plurality voting per se. Rather, theirs is a tempered, spasmodic and election-driven response to particularly egregious instances of inequitable conversion of votes into seats. With few exceptions, calls for electoral reform have been most numerous, as they were following the last three federal elections, whenever parliaments were elected with vote/seat ratios that were clearly skewed by parties and regions. Canadian history is littered with examples of newspaper articles, letters to editors, scholarly studies and conferences (such as this one!) in which academics, members of the media and civic-minded individuals have called for electoral reform. Their irregularity, however, demonstrates that concern about the electoral system is circumstance-driven.

To a considerable extent these well-intended, though periodic, initiatives have amounted to little more than whistling in the wind. Why? Because several fundamental conditions have not been in place that collectively would have to have been met before changes to the electoral system could be made.

A basic condition of the reform of any representational building block is that until such time as the governing elites accept the case for modifying it, changes cannot take place. There is no evidence of any measurable level of support for electoral reform among Canada’s governing elites at the present time. Such reform proposals as are made come from some, but by no means all, opposition members or, as in the case of the Greens, parties without elected members. The probability of a government agreeing to changes at the present time is low, for reform can scarcely be said to work to their advantage. With few exceptions governing parties at both the federal and provincial levels have benefited from plurality voting, with the result that on the issue of reforming the method of election by which they won office governments’ self-interest has outweighed the public interest as defined by electoral reformers.

What could change that is a series of unstable, possibly coalition or minority single-party governments in which minor parties successfully bargain for electoral reform. Alternatively, as was the case in New Zealand in the early 1990s, profound public dissatisfaction with and disdain for politicians and parties, following on the heels of an influential and respected commission of inquiry examining alternative electoral methods and recommending one, could be the catalyst needed to prompt the principal political actors to accept changes to the electoral system.

At the moment, neither of these alternatives is in the works in Canada. There are several reasons for this. The majority Liberal government, notably the prime minister, shows no interest whatsoever in electoral reform. Likewise, there have in the past been no Canadian equivalents to New Zealand’s “agenda-setting” public interest groups on electoral reform, although such relatively new organizations as Fair Vote Canada are gaining a measure of serious attention. The level of public dissatisfaction with the electoral system and politicians has yet to reach the level that it did a decade ago in New Zealand. As well, Canada’s equivalent to New Zealand’s commission on electoral reform (the Lortie Commission) evinced not the slightest inclination to move away from plurality voting.

If a continuing and manifestly general dissatisfaction with plurality voting were present amongst the Canadian electorate, and if there were widespread agreement on a single alternative espoused by a respected national commission of inquiry, that would be, as they say, a “no-brainer.” Those conditions would properly lead to genuine and far-reaching demands for electoral reform that those in government would ignore at their peril.

But is the case for electoral reform as compelling when the principal arguments for reform derive from periodic dissatisfaction with the results of a particular election or set of elections as expressed by a limited number of individuals (academics, occasional opposition members and the print medium)? Without extensive and profound disapproval on the part of the electorate with the current system, coupled with general agreement on an acceptable alternative to plurality voting, the push for electoral reform in Canada is likely to fall on deaf government ears. Given the abundance of alternative proposals bandied about in Canada over the recent past, ranging from German-styled MMP elections, through alternative voting, run-off elections and single transferable votes, to two member-plurality elections, it is fair to say that agreement on a preferred option to the current system is some distance away.

There are two institutional and territorially-bounded filters through which our current plurality vote system works. The first is the single-member electoral district, the second federalism. Both constitute important representational institutions for the periodic reallocation of federal seats among the provinces, the designing of district boundaries, the aggregating of votes, and the eventual determination of election winners and losers.

A recent study in the American Political Science Review by Carlos Boix compared electoral reform in a number of countries. It concluded that Canada is not naturally predisposed to electoral reform because of a complex interrelationship between its federal system and the geographical distribution of its citizens by language groups. Canada is a territorially large federation in which the two principal linguistic groups are geographically concentrated—francophones predominantly in Quebec, and anglophones predominantly in all other parts of the country. Unlike several European countries, Canada’s principal social cleavage is not distributed more or less evenly across the country. If it were, that would serve as a powerful inducement to replace plurality voting with a more proportionate electoral scheme designed to protect the linguistic minority and to guarantee it a measure of parliamentary representation. As that is not now the case, nor is it likely to become so in the foreseeable future, the geographic distribution of the two dominant language groups and the federalized institutional structure within which their electoral choices are aggregated collectively lend no support to the case for a reformed electoral system.

Chart 1 highlights the principal conditions that need to be met before Canada’s electoral system can be changed to some as yet undetermined, non-plurality voting system. Of those, the support of governing elites and the agreement on a single alternative to the current system are clearly the most essential. Others, such as the support of other agencies, academics, the press, and the like, as well as the extra-parliamentary resources that might play a pro-reform advocacy role in the debate over moving away from plurality voting, are no doubt important to shaping public and elite opinion. As valuable as they may be, they are not as critical to the exercise as the government leaders who play the vital constitutional and decision-making role on such questions.

The obstacles to reform are, for the most part, attitudinal on the part of both the politicians and the general public. Leading politicians on the government benches do not, so far at least, favour change, and the electorate has, for the most part, shown little interest in the issue. Federalism may not be either a hindrance or a help on this issue, though Boix’s analysis serves as a reminder that the geographic distribution of voters along a key demographic variable helps to explain why reform has so far gained relatively little public support.

If federalism offers any lessons at all on the question of electoral reform that would need further exploration, it is that for varying lengths of time in the 20th century two of the three prairie provinces and British Columbia used nonplurality electoral systems before reverting, once again, to the plurality vote. What were the reasons that these provinces abandoned their respective experiments? Does the answer confirm that “far away pastures look greener” and that a return to first-past-the-post voting offered something that the more proportional schemes had failed to deliver to the three provinces? That certainly was part of the argument that led Manitoba to return to plurality voting in the 1950s.

In sum, given both the absence of a single alternative strongly favoured by an electorate seriously disaffected with plurality voting and the failure to date of governing elites to have embraced the cause of electoral reform, the chances of adoption of a reformed electoral system would have to be judged as low at present.

The expression “reforming the electoral system” has a pleasant ring about it. It suggests improvement, progress, and an ultimately fairer and more democratic electoral system for all citizens. There is no doubt much in the debate over Canada’s electoral system that confirms the inherent justice of the attempt to alter Canada’s method of election. But equally it is essential to understand fully that no electoral system is neutral. How it distributes votes into seats ultimately affects the composition of institutions and the content of public policies. Accordingly, the relationship between the constitutional principles and institutional framework on the one hand and the representative and electoral systems on the other deserves full consideration before the plurality system is modified. This paper has argued as well that certain basic variables must first be in place before the electoral system can be reformed. Until those tests have been met, a reformed electoral system in Canada remains largely a speculative academic question and, possibly, the latest in a long list of “whistling in the electoral winds” exercises in Canada.

Photo: Shutterstock