When you think about it, a city is truly an amazing thing. Hundreds of thousands, even millions of people live in close proximity to each other, go about their daily lives, find shelter and work, interact in groups large and small, move about and somehow meet their individual and collective needs in a giant beehive of activity. Then again, when you think more deeply, not everyone in a given city finds work, security or good living conditions, and some cities are particularly bad at meeting their residents’ needs. For every Toronto, there is a Mogadishu.

But overall, Canadians can legitimately be proud of the cities they have built. These offer a high quality of life to most citizens, no small feat when compared with urban conditions throughout history. And yet long-term prospects are not as rosy as we would like them to be. Our urban centres may be on the road to becoming “smart cities” technologically speaking, but that does not necessarily mean they will be healthy or fair places to live. And Canada’s cities are particularly vulnerable because they are extremely dependent on higher levels of government; important policy choices are being made for cities but not by cities. It is not clear that politicians in federal or provincial governments will do the right thing for our cities as their economic choices get tougher.

Meanwhile the bifurcation of the economy between high-skill and low-skill sectors is undermining the middle-class-society that we have built in the West. The 20th-century city was the city of the middle class. In the first two-thirds of the century, it fulfilled for most the promise of a rising standard of living, as seen in the growing size of homes and number of cars that households could afford. In the final third, it even delivered a higher quality of life to most, as witnessed in the rich expansion of cultural and natural amenities, from street festivals to hockey arenas and trail systems. But the time is ending when such a vast proportion of the urban population can legitimately claim to be part of the middle class that our cities serve so well.

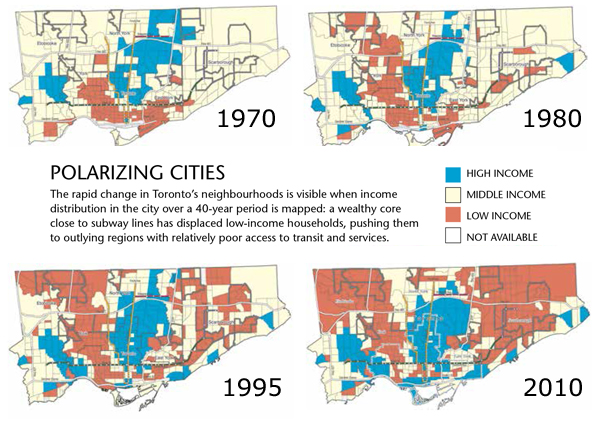

The shift to a postindustrial, knowledge-based economy has already started to increase inequality in Canadian cities, and housing markets are quickly translating this change into a new spatial segregation. So far, the gap between rich and poor has been increased mostly by a rise of incomes at the top. Since the 1990s, the richest have seen their revenues and wealth increase quickly, while those in the middle or at the bottom of the economic ladder have seen theirs stagnate. While there is no reason to expect a slowdown in the rise at the upper income end, there is much evidence to make us fear an absolute reduction among lower incomes. The economic conditions that gave us the contemporary city — the city of the middle class — will not last.

It will take great political will — the sort of will that governments seem less and less inclined to muster — to reduce the impact of economic change on the living conditions of the bottom two-thirds of the population. The revolution in information and communication technology will empower individuals in all spheres of life, but it is unlikely to undo with one metaphorical hand what it is doing with the other and be a source of economic equality. Accumulated debt in government budgets and in pension funds will reduce our margin of manoeuvre, and climate change will impose additional economic burdens. In this context, our mechanisms for the distribution and redistribution of wealth may not continue to ensure the average quality of life and modicum of equality that we have known for half a century. Our very imperfect systems of industrial capitalism and social welfare may well become objects of great nostalgia. So, too, may the cities we know today.

The Canadian city is changing, and the change is pointing to a city of “hip” neighbourhoods for the wealthy minority and of “problem” neighbourhoods for the majority. The precise geographic distribution of wealth and quality of life will vary from city to city. But overall, the rich will occupy older, more central parts of the metropolitan area, those that are more attractive and walkable and offer a greater mix of public and private services, as well as suburban neighbourhoods with a high-quality building stock, great natural beauty and easy access to high-end services.

The rest of the population will occupy a vast suburban territory with housing of poorer construction quality and a far less attractive public realm. To varying degrees, this trend is becoming visible in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.

The suburbanization of poverty is a new reality. As central neighbourhoods are gentrifying, households with lower incomes must seek housing farther away from the centre. Paradoxically, the rich, who can afford to buy cars, are taking over neighbourhoods that are well served by transit; the poor, who depend much more on public transportation, are forced to live in automobile-dependent areas. Preventing the creation of suburban slums, whether in high-rise complexes or in subdivisions of bungalows, and dealing with these slums once they exist will be major challenges to municipal and metropolitan authorities. It is not clear how willingly and how effectively they will meet these challenges, and what support they will get from higher-level governments to do so.

What can be done today to lessen the impact of growing inequality and prevent the emergence of suburban slums? The most important action is, in a way, a non-action: it is to maintain our social welfare system, which makes poverty more bearable and has historically helped to make Canadian cities much more civil and livable than they otherwise would have been. (To be able to keep the social welfare system more or less intact will, in turn, require fiscal policies to reduce the long-term debt burden and economic and education policies to increase productivity.) Without redistribution through transfer payments, tax breaks and public services — among which public education is paramount — no amount of local action will make a real difference.

But with a basic social safety net in place, urban policies can help, particularly if they are adopted and implemented at the metropolitan level. They should include substantive investments in transit services in the suburbs, from rail-based services where densities are highest to car-based services (car sharing, taxis) where they are lowest. Measures should also include infrastructure improvements and regulatory changes to foster the densification of major suburban corridors and even of whole suburban areas, as well as incentives to maintain and repair housing.

Policies should also be adopted to nurture the growth of the social-economy and support initiatives to create cooperatives, barter systems, pop-up facilities and other nonmarket arrangements or informal mechanisms that meet individual and community needs. Meanwhile, it will remain necessary to attend to some of the pressing problems that are already on the policy agenda, from the renewal of older infrastructure to the preservation of natural areas.

Much hope is being placed in the advent of a “metropolitan revolution” in which political, business and civic leaders will work together, pragmatically, to solve urban problems, without waiting for provincial and national politicians to get their act together. Alex Mazer has recently discussed this possibility in these pages. But as he remarks, Canadian metropolitan areas do not currently have the political leadership, fiscal resources and institutional basis that some of their US counterparts have.

We are seeing some progress in metropolitan and municipal governance, and we can find solace in the existence of a vibrant civil society in our cities. In Montreal, for instance, government, business and community actors are working together to lower the terrible high-school dropout rate, and not-for-profit organizations are helping to spread innovative practices in citizen participation, urban ecology and social entrepreneurship. But even in economically and socially richer urban regions, costly measures will be needed to prevent some of our neighbourhoods, particularly in the suburbs, from becoming place of human misery and objects of shame.

In our present system of government, cities cannot redistribute income and equalize life chances in a substantive way. Only purposeful policies at higher levels of government can do that. But our metropolitan areas must be actors and beneficiaries in a virtuous cycle: redistributive policies are more likely to be adopted or supported when there is economic growth; economic growth is increasingly dependent on the performance of our metropolitan areas; that performance, in turn, depends in large measure on social and economic policies to tackle structural problems in the economy and in society.

Canadian cities rose to the top of global rankings of urban quality of life in part thanks to such policies. Where these fail, as they do so strikingly for Aboriginal populations, for example, living conditions quickly become abysmal, and no amount of local planning, however much it is participatory, can make a real, long-term difference.

As society becomes more unequal and the urban landscape starts showing signs of new social polarization, we cannot expect salvation from information technologies or from civil society organizations. Whatever individual and collective empowerment these may deliver, they will not suffice to compensate for the new inequality of postindustrial society and for the new urban geography of wealth and poverty. What is required is a frank discussion on whether we want the Canadian city to survive as we know it today, quite livable and relatively fair, and on what price we are willing to pay to make that happen, or are willing to pay if we don’t.

Photo: Shutterstock by shipfactory