Our view of the evolution of Quebec in the last decade is obscured by three elements. First, from the Meech debate of 1990 to the resignation of Premier Bouchard in early 2001, it sometimes seemed that scarcely anything but political debate has gone on in the province. Second, Quebec’s policies towards the rest of the world and Ottawa’s response to them may seem wholly attributable, not to real structural evolution, but to political posturing aimed at the next independence showdown. Third, in any examination of economic vital signs, the inevitable and relevant comparison with Ontario usually puts Quebec at a disadvantage—as though sitting besides a giant necessarily means that you are a dwarf.

But beyond these elements, and intertwined with them, Quebec’s transformations during the 1990s, mostly coming to fruition in the second half of the decade, deserve to be weighed on their merits. The view of this essay is that, in the last ten years, both Quebec’s economic and political elite and Quebecers at large wanted Quebec to become a region-state—that is, to act increasingly as a specific entity whether or not it became independent from Canada; that Quebec needed to become a region-state in order to achieve optimal growth; and that it was further pushed into becoming one by the peculiar political context in which it found itself.

Quebec’s elite made two macroeconomic decisions in the late 1980s and early 1990s that prepared the transformations to come. The first was Quebec’s bipartisan support for the Free Trade Agreement in 1988. At the time, most of Quebec’s exports were destined to the rest of Canada, first and foremost Ontario. By then the business class was primarily francophone. Diversifying exports to the U.S., across the political, legal and linguistic U.S. border should have been a more frightening challenge for them and their electorate than for their Ontario counterparts. As pointed out by John Helliwell, “two countries [or in this case a region and a neighbouring country] sharing a language are estimated to have two-way trade flows more than 50 per cent larger than those between otherwise similar countries.” That is the standard he found for OECD countries. Which means that, given a similar starting point, English-speaking Ontario should do 50 per cent better than French-speaking Quebec at trading with the U.S. Helliwell has also argued, based on a gravity model developed by John McCallum, that in 1990 Quebec’s reliance on interprovincial trade over trade with U.S. states of comparable size and distance was even greater than that of other provinces. McCallum had shown that the intensity of province-to-province trade was, on average, 21 times greater than that between province and state. Helliwell found that, for Quebec, it was 26 times greater. “National borders matter even more for Quebec than for the rest of Canada,” he wrote.

Yet Quebec’s new entrepreneurs were enthusiastic in favouring free trade with the U.S. Politically, then-Premier René Lévesque had given a first positive signal in a speech in the U.S. in 1984. Later a risk-averse Premier Robert Bourassa joined the movement. In the election of 1988, Quebec and Alberta were the only provinces to give a majority of votes to Brian Mulroney, thus bringing the FTA into place.

Then came the GST. Quebec’s Liberal government, supported by the PQ opposition, and the Quebec business class, saw the competitive advantage in taking the sales taxes out of the structure of the manufactured product, thus lowering its cost when it crossed the border. They harmonised the Quebec sales tax on the same principle to further lower the cost of exported goods. There was some loss of short-term revenue—about $2 billion—but it was seen as a worthy investment in the expansion of exports, and as a leg up on Ontario, where this tax adjustment was politically out of the question.

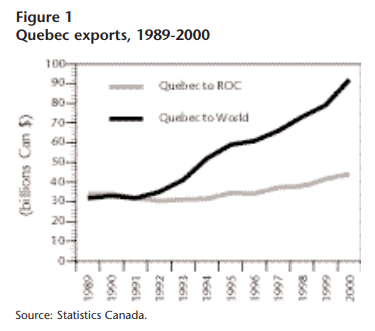

And the anticipated expansion of exports did come. When the decade closed, Quebec was selling almost twice as much abroad as it was selling in Canada. By 2000, Quebec was the U.S.’s sixth most important trading partner, accounting for more of U.S. trade than the UK, France, Germany, Brazil or Russia.

This amounts to a commercial “de-Canadianization” of Quebec. But if anything, interprovincial comparisons are even more interesting. Using data that span the decade, from the previous economic peak in 1989 to what we now know to be the latest peak, in 2000, one notes, first, that Canada as a whole went from near equilibrium between interprovincial trade and external exports to a position where international exports became twice as important as interprovincial exchanges. That is an extraordinary event in and of itself.

What is striking about Ontario and Quebec is the growth of their international exports in the decade. At the end of the economic decade, Canadian exports were, on average, 180 per cent higher than they had been in 1989, which is of course very high. But Quebec’s exports stood at 190 per cent of their 1990 value and Ontario’s at 192 per cent. Corrected for population growth, however, Quebec actually did better than Ontario: 173 per cent vs. Ontario’s 153 per cent. Furthermore, the change in both provinces’ international trade ratio (that is, their trade relative to GDP) is unmatched. Compared to the already high provincial average growth rate of 74 per cent, Quebec’s trade ratio grew by 94 per cent over the decade, Ontario’s by 90 per cent—which means that Quebec overcame both Helliwell’s language border effect and its traditional over-reliance on interprovincial trade.

Overall trade volumes tell only part of the story, however, even if it is a structurally essential part. The content of Quebec’s exports also changed drastically. Raw materials exports have been overtaken by aerospace production and telecommunications—although these were both hard-hit by recent events. Quebec has moved from pulp and paper and aluminium (although it remains a world leader there) to building and selling half of all the civilian helicopters in the world. Quebec is now a net importer of raw materials, even more so than Ontario.

The structure of its intra-industrial trade also sets Quebec apart from its Canadian neighbours, and this could be viewed as another indicator of region-state status. Data show that the intra-industrial commerce that Ontario and the rest of Canada have with the U.S. outweighs their intra-industrial commerce with the rest of the world. But in Quebec, the reverse is true, thanks largely to Quebec’s greater European connection.

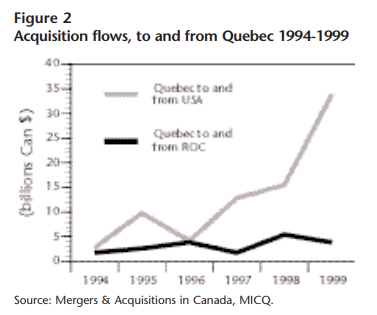

If the flow of goods into and out of Quebec became more American than Canadian in the 1990s, what can be said about the flow of cross-border investment? Data on investment are notoriously hard to break down into foreign and interprovincial private investment, but relying on the set of acquisition figures compiled by Crosbie & Co. for its “Mergers & Acquisitions in Canada” series, we see that over the 1994-99 period for which provincial data was compiled by the Quebec Department of Industry and Commerce, the north-south flow was stronger than the east-west flow. This was also true in the rest of Canada, but it was especially true in Quebec. Though Quebec accounts for 22 per cent of Canada’s GDP, its share of U.S. acquisitions in Canada was 33 per cent over this period, while its share of Canadian acquisitions in the U.S. reached 49 per cent. Of the $63 billion worth of acquisitions that Quebec corporations made north of Mexico in these years, fully 82 per cent went to the U.S. Also, in the same period, U.S. acquisitions in Quebec were almost three times as important as those from the rest of Canada—$27 billion vs. $10 billion, a gap that is growing over time. Investment was clearly another important force in the de-Canadianization of the Quebec economy.

Now that the record is clear, we can ask how much of it is attributable to the actions of Quebec’s government and business elite, and how much to the Canadian economic and political environment. As always, causal effects obviously cannot be drawn with precision, and these changes are more deeply rooted than in policy decisions taken in the latter part of the 1990s. Yet what emerges is the striking convergence between the decisions of the policy actors and the economic results at hand.

By mid-decade, Quebec was acting forcefully in the region-state mode. It did so with the very active participation of a business class that had not supported the Yes committee in the 1995 referendum but fervently wanted an economic revival. The participation of leaders of industry in Premier Bouchard’s economic summits of 1996, sometimes over the objections of federal ministers, further cemented their bond with the Bouchard government.

Quebec’s action was twofold. First, on the fiscal front, the six budgets from 1996 to 2001 changed the fiscal rules for investors. Today, if the general tax burden on Quebec businesses as a whole—including income, capital and payroll taxes—is on a par or even slightly lower than in Ontario, it has become markedly more favourable for domestic and foreign investors. In terms of investor-friendly fiscal packages, Quebec first matched its Canadian neighbours, then its American neighbours, and most recently Ireland. As we speak, a foreign or domestic investor would need an extremely inept accountant to pay any provincial taxes at all in Quebec, including parts of the payroll tax, in the first five to ten years following the investment. A KPMG study has shown that Montreal’s overall costs were lower than in any other major city in Europe or North America—a result confirmed by similar KPMG studies currently displayed on Ontario’s and Alberta’s official websites. Apart from its tax policies, Quebec contributed to keeping these costs low by freezing the cost of electricity from 1998 until 2004.

In terms of personal income tax, Quebec’s provincial burden is greater than anywhere on the continent. But this measure is a very poor, in fact misleading way to assess overall real costs for individuals. An Alberta-sponsored KPMG study conducted this year showed that the total cost of living, including taxes, is lower in Montreal than in Toronto or Vancouver, for all income classes studied, including those with income ranging from $40,000 to $150,000 a year. (Alberta cities, of course, do even better.) A similar study done in 1998 for the Quebec government showed that Montreal’s advantage continued on up the income scale, even as high as $250,000 a year. Among the 14 largest North American metropolitan areas, Montreal ranked first for families earning up to $50,000 a year, and was no worse than average for other families, all the way up the scale to $250,000, and for single persons up to $75,000 a year. All in all, Montreal was never worse than eleventh. Even so, the Quebec government has moved to reduce tax rates in the last four years. Unable to match Ontario or the U.S. on the overall rates, however, it again created a targeted regime. For foreign staff moving to Quebec in the new economy, some financial sectors, and some areas of university research, the rule is simple: no provincial income tax for five years.

So, to use Philip Cooke’s terms, Quebec as a region-state is trying to take both the low road and the high road to success: the low road by benefiting from low costs and targeted low corporate and income taxes for investors and foreign staff, and the high road both by investing in education at a higher per capita rate than its neighbours or the OECD and by maintaining social transfers high enough to: generate a Gini coefficient that shows less income inequality than anywhere on the continent (except the Atlantic provinces); foster a social environment where the poverty rate is lower than in Ontario or the U.S.; and implement a family and children’s agenda that is unmatched. In overall terms, from fiscal year 1995/96 to 2000/01, Quebec’s own-source revenue grew by 39 per cent (compared to 41 per cent in Ontario) and its program spending grew by 13.7 per cent (vs. 5.4 per cent in Ontario). In a nutshell, Quebec made itself fiscally competitive to investors without losing its social-democratic soul.

The second front in Quebec’s economic campaign was to actively seek investors. To put it simply, the Quebec government does not think that “if we build it” (the fiscally competitive house), “they will come.” Given the linguistic, cultural, and political uniqueness of the place—which isn’t viewed positively in an American context—Quebec feels it needs to put resources, first into “building it,” and then into bringing the client in to see it. Clearly, it takes more energy and time to explain Quebec’s distinctiveness in the U.S. than, let’s say, Ontario or BC’s comparative advantages. Quebec leaders intuitively came to the conclusions reached by Helliwell and Jean-Philippe Platteau, whose studies suggest that the absence of shared language, values and institutions are likely to increase the costs of making and enforcing contracts, including, of course, those associated with FDI.

A report tabled at the 1996 Montreal economic summit demonstrated that, in the mind of American economic decision-makers, Montreal had fallen off the list of relevant North American metropolises in technology, education, science and the like. Site locators, essential agents for investment, had all but forgotten Quebec’s existence. In the wake of the 1995 referendum, Quebec’s press coverage in the U.S. was dismal.

In short order, between 1996 and 1998, the Quebec government expanded its investment recruitment services by an order of magnitude. A revamped agency, Investissement-Québec, was formed that would soon win awards from American site-locator publications. The Societé Générale de Financement was also re-engineered to become much more active in seeking foreign investments, which it was able to do thanks to its ability to take an important minority share in the investments.

Quebec also made an aggressive effort at marketing. The Premier travelled to nine American cities with the leaders of Quebec’s business class in tow and made measurable headway in changing the perceptions of economic and political decision makers. Whether with these “Missions Québec” or alone, he went to the U.S. about four times a year, meeting governors, investors and editorial boards. This effort was to have reached a high point in September of 2001, with “the Quebec season” in New York, a $15-million multi-faceted initiative to drive home the point that a new Quebec has arrived. Though for obvious reasons the Quebec season was postponed, the positive coverage that Montreal and Quebec City have had since 1998 in the U.S. and U.K. press in general and in the economic press in particular stands in stark contrast with the press they were getting in 1995.

The combined effect on-site locators was significant. While Quebec still is not spontaneously put on the list of preferred North American sites for a potential investment, when it does get on the list, it very frequently moves right to the short list. Debate is acute in Quebec about some of the investment decisions made these last years by the new public investment agencies. Yet the overall figures are striking: In 2000, having reached cruising speed, Investissement-Québec organised 100 foreign missions and greeted 200 potential investors in Quebec. For the year, its portfolio yielded 37 new foreign investments worth $1.2 billion. As for the SGF, its 2000 annual report states that the number of new foreign investments it generated went from four a year in 1996 to 49 in 2000, with investments going from $78 million in 1996 to $2.4 billion in 2000. The cumulative impact on direct jobs (not counting construction) went from 800 in 1996 to 10,200 in 2000, though there is some overlap between the figures reported by the two institutions.

If the Quebec elite clearly worked at making Quebec a region-state in the latter part of the 1990s, and if the American market and American investors provided the opportunity to re-deploy the province’s economic activity north-south rather than east-west, the federal government and the Canadian economy also played a part in these changes.

The internal trade picture encouraged Quebec to find growth abroad. Over the decade, interprovincial exports in Canada grew by 40 per cent in the aggregate and by 55 per cent if a simple average is made of the provinces’ progress. What was the story for Quebec? Interprovincial trade grew by less, just 30 per cent, compared to Ontario’s 28 per cent. Among all Canadian provinces, Quebec and Ontario had the weakest growth in interprovincial exports over the decade. For these two provinces, economic growth lay primarily outside Canada’s borders.

On the political front, it was soon understood that the task of promoting Quebec as a good investment venue in the U.S. would be a lonelier affair than could otherwise be expected. In the post-referendum period, Canadian diplomats in the U.S. sometimes actually fuelled the negative perception of Montreal and Quebec in briefings to investors. The example came from on high. The Prime Minister made a disparaging remark about Montreal’s economy during a major speech at the New York Economic Club. The Premier of Ontario, Mike Harris, also did his share. In an interview given to the Sun newspaper chain in early 1998—at a time when Montreal’s economy was clearly improving—he said: “It’s tough to go to Montreal at rush hour and see no rush hour.” He added, “Montreal was a great city”; “it is not now.” His remarks reflect the very dismissive tone of the Toronto economic press about Quebec and Montreal in those years.

The coolness was somewhat reciprocated. Quebec’s promotional efforts were important in the U.S., as we have seen, and other important missions involving the Premier and representatives of the Quebec elite were organised in China, Mexico, Argentina, Chile, France and Catalonia. Yet there was scarcely any effort from Quebec to try and change perceptions in or attract investments from the rest of Canada. Premier Bouchard travelled there almost exclusively for Premiers’ conferences. Organising a “Mission Quebec” to Toronto or Vancouver was sometimes contemplated, but the certainty that any positive economic message would be overwhelmed by the political debate on sovereignty made the endeavour not worth the investment.

Thus, in an interesting twist, real structural change and politics combined toward the same end. Quebec was becoming a region-state mainly for economic reasons. But the sovereignist premier, Lucien Bouchard, had made financial and economic growth the linchpin of his pro-independence policy. During what was then believed to be a short interval until the next referendum, Ottawa’s main line of public argument was therefore that political instability was hurting Quebec’s economy. An upturn would ruin this argument, and it was indeed ruined when the upturn became undeniable in 1998. It would be interesting to document what, if anything, Ottawa may have done to prevent the upturn, which would have been a politically difficult high-wire act.

The federal government was in the process of reasserting itself as an indispensable government in the life of Quebecers, and wanted to be seen as a direct contributor to their well-being, especially in the francophone regions that were politically dominated by the sovereignists. At a time of reduced spending, it achieved this primarily by a massive effort of branding its existing contributions and targeting dwindling resources in those activities with most visibility. Yet it refused to participate in some high-profile big-ticket items, leaving the entire tab to the Quebec government despite strong pressure from Montreal’s business class. The expansion of Montreal’s Convention Centre and the rehabilitation of the failed Mirabel airport (a purely federal blunder), are the main examples. The decision of the Prime Minister, against previous commitments, to approve the choice of a direct Nova-Scotia/USA route for the new gas pipeline of Sable Island against the Nova-Scotia/New Brunswick/Quebec/Ontario proposal, which would have made more national sense and would have benefited Quebec, was also seen as uncharacteristic of what a “favourite son” in power would do. The federal attempt to favour Alberta-based and bankruptcy-bound Canadian Airlines over Montreal’s sounder (at the time, at least) Air Canada in the necessary restructuring of the airline industry was another case in point.

These big-ticket items are marginal compared to the full federal presence in the Quebec economy but they gave a general tone that Ottawa was not consistently “onside” with the Quebec elite’s efforts to lift the province’s economy. That federal investment was also experiencing a period of contraction due to deficit-cutting could not help but fuel this impression. From its 1994 high point to the 1998 low point, federal capital investment—Ottawa’s most direct input—fell by 31 per cent in Canada as a whole. In Ontario, the reduction was just 19 per cent, but in Quebec it was 33 per cent, a decline that took investment from $834 million in 1994 to $560 million in 1998.The federal vacuum was greater in Quebec than in the ROC, Ontario in particular.

There is no question that while Quebec suffered from federal underinvestment on the productive side of the ledger, it was a net gainer in the remedial aspect of the federal presence: equalization and the redistributive effects of the CHST and unemployment insurance. But even in these fields Ottawa moved to stem the financial flow to Quebec over and above the severe across-the-board cuts in CHST funding of that period. Pierre Fortin estimates that by shifting a greater number of the unemployed to provincial social assistance successive reforms of EI added a burden of $845 million to the Quebec treasury for the 1990-1997 period, and $100 million for each of the succeeding years. In early 1999, a surprise CHST reform wiped out the “advantage” Quebec reaped from the previous accounting basis. Ottawa now shifted its fiscal assistance growth entirely to per capita terms. This change compounded the UI reform damage and reduced Quebec’s expected share of new funding by $330 million for that year alone or by $1.8 billion over five years. This structural reform, long advocated by Ontario and Alberta, who got the lion’s share of the new funding, coincided with a greater than expected equalization payment to Quebec, thus explaining the timing of the feds’ action.

For all these reasons, the Canadian environment in the late 1990s effectively encouraged Quebec to reduce its reliance on the Canadian market for commercial growth, its reliance on Canadian diplomacy, political leadership and economic media for help in attracting investment, and its reliance on the federal government for productive investment, budgetary help and remedial measures. The environment instead reinforced Quebec’s inclination to look to its own resources for strength and direction, and to look outside Canada for growth, opportunity and allies.

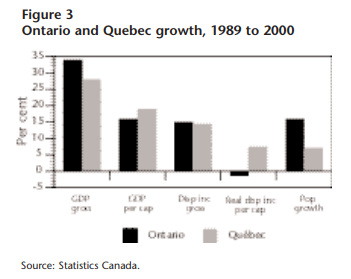

Trade and investment trends show how Quebec modified its relationship with its neighbours during the 1990s. What impact did these changes have on the Quebec economy? Between the 1989 and 2000 peaks, Ontario grew faster than Quebec. Its GDP rose 34 per cent compared to Quebec’s 28 per cent.

Adjust the numbers for population growth, however, and you get a different picture: Ontario’s per capita growth was 16 per cent, Quebec’s 19 per cent. Now deflate the numbers with the GDP deflator and look at real per capita disposable income and the difference is even more stunning: zero growth (-0.3 per cent) in Ontario, 7.4 per cent growth in Quebec. So, clearly, if you are a GDP, you did better in Ontario. On the other hand, if you are a person…

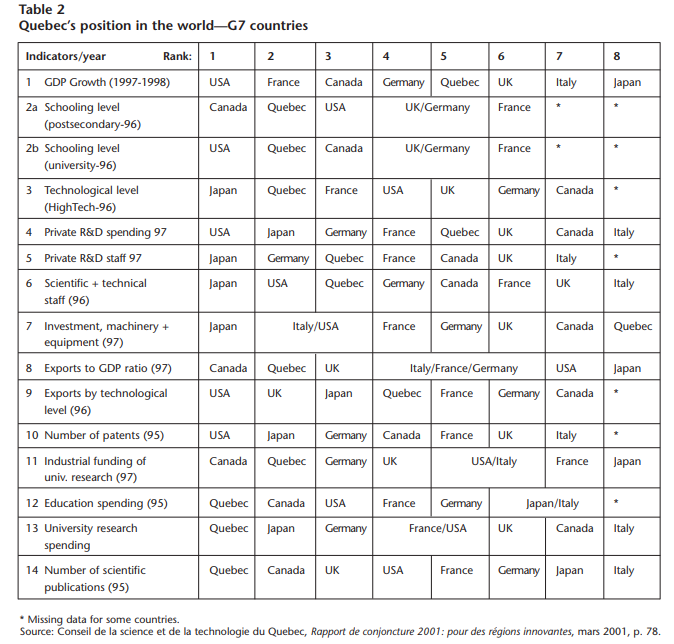

Although it is seldom seen as such, Quebec has become an economic powerhouse. Taken alone, its GDP went from being the 23rd in the world in 1976 to 15th in 2000, and sixth in the Americas. Compared to the G7 countries, its economy now has the highest proportion of high-tech production, just after Japan. And the outlook is also promising. In a report on innovation issued in the spring of 2001, the Conseil quebecois de la science et de la technologie produced a table of 14 indicators that are seen as signs or precursors of innovation, including investment in education, R&D spending, the technological level of production, the proportion of technical personnel, the export rate, business financing of university research, patents, output of scientific publications and some others. It compared Quebec’s data with those of the G7. In eight of the 14 variables, Quebec was in the top three, clearly ahead of Canada as a whole. Only the U.S. fared better overall.

There is no doubt that these transformations have occurred as a result of Quebec’s strengthened links to the U.S. economy. But the fact that it could flex its R&D muscles in high-tech was due to 25 years of consistent fiscal cocooning and to the education revolution that brought Quebec from the lowest schooling ratio on the continent in 1961 to one of the highest in the Western world in the late 1990s.

An essential element in this transformation, though difficult to measure in pure economic terms, is what Tom Courchene would call a “locational externality,” an advantage specific to that place and no other. In my view, Quebec’s crucial externality is linguistic, and it helps explain why the linguistic border effect found elsewhere in the OECD by Helliwell has not been an impediment to Quebec’s commercial surge. In his research, Helliwell finds no trace of this effect for Quebec and concludes that the level of French/English bilingualism is sufficient to eliminate this handicap both for province-to-province trade and for province-to-state trade.

This hypothesis is worth looking into. If there was no language border effect before the 1970s, it is simply because the people then in charge of the economic interface between Quebec and the Anglo-American continent were anglophones. In the 1960s, an absolute majority of managers of Quebec firms (including 80 per cent of middle-managers, and 60 per cent of senior managers) were members of the English-speaking minority, and most of the time they worked only in English. Today, although anglophones still enjoy over-representation in management (at 26 per cent in 1988, the last year for which data are available, despite being 10 per cent of the population), French-speakers are for the first time in the majority (at 58 per cent, compared to their 81 per cent share of the population) Allophones account for the remaining 16 per cent. With francophones now primarily in charge of the economic interface with anglophone America, there should have been a surge of the language border effect.

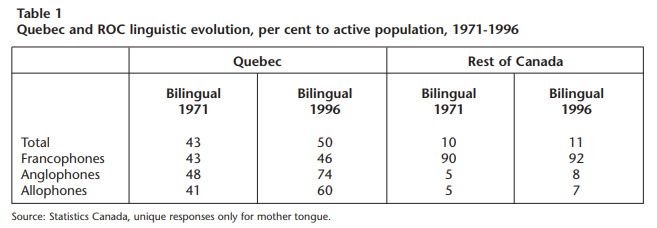

What emerged instead, however, was a new business and managerial class which speaks, to quote American scholar Marc Levine, “a French-dominated bilingualism.” This has little to do with Canadian linguistic policy. For the record, in Canada outside Quebec, decades of effort under the Official Languages Act brought bilingualism there from a paltry nine per cent in 1951 and 9.4 per cent in 1971 to 10.8 per cent in 1996.

The transformation is Quebec’s very own, and is the product of schooling, economic flows, migration and decades of linguistic legislation. In the 15 years from 1971 to 1996, the proportion of the active population that knew French went from 89 to 96 per cent. The proportion that is bilingual went from 43 to 50 per cent, thanks to a slight increase in bilingualism among francophones and a major rise among non-francophones. In the Montreal metropolitan area, Quebec’s economic centre, the level of bilingualism reaches 63 per cent in the active population, and 80 per cent among managers and engineers.

Somewhere between 1971 and 1996 a threshold was crossed that has prevented the advent of a linguistic border effect. Making French the real, internal, functional language while at the same time expanding the use of English as an indispensable interface tool, and doing so at a time when the linguistic makeup of the managerial class was changing radically: that is the unheralded, bipartisan achievement of 30 years of linguistic experiment in Quebec.

But there is more. When a majority of skilled francophones and anglophones are bilingual and a majority of allophones speak three languages, a potent locational externality comes into play. This operational bilingualism enables Quebec to provide a unique, real-time connection to innovations in both French Europe and anglophone North America. It has effects in intra-industrial trade, as we have seen, in research and development, in post-secondary education, in public policy experiments, in culture and doubtless in many other areas, as well. Quebec has given itself the ability to import, blend and then re-export new concepts. No outside translation required. In my view, this advantage has only just begun to pay off.

This is an expanded the version of a paper presented to the IRPPCIRRD conference on “The Art of the State in a World Without Frontiers,” Montebello, October 2001.

Photo: Shutterstock