From Native reserves to suburban schoolyards, from cross-border communities to downtown convenience stores, there are few places untouched by contraband tobacco. The issue made headlines throughout 2010: newspaper series and research papers chronicled the shocking increase in contraband’s use and availability, experts sparred over solutions, and governments announced new strategies to tackle the problem. Meanwhile seizures of illegal products continued to climb, as sales of legal cigarettes dropped dramatically.

In its 2008 Contraband Tobacco Enforcement Strategy, the RCMP defines contraband tobacco as “any tobacco product that does not comply with the provisions of all applicable federal and provincial statutes [including] importation, stamping, marking, manufacturing, distributing and payment of duties and taxes.” Contraband products range from brand-name cigarettes resold illegally, without tax, to unmarked cigarettes sold in plastic bags. In Canada today, the price of a legal carton of 200 cigarettes, including tax, varies between $70 and $106, depending on the provincial or territorial tax rate. The same quantity of illegal cigarettes can be purchased on the black market for as little as $6 or $10.

Most contraband is sold in central Canada but produced in the United States. It is smuggled and distributed by criminal networks through the Aboriginal reserve of Akwesasne, which straddles the Canada-US border. The RCMP has also documented a proliferation of illegal factories on Canadian reserves, run by Canadian biker gangs and the Korean, Chinese and Russian mafias.

Legal, licensed Native-owned factories also operate in Aboriginal communities, including Kahnawake and Six Nations. According to a 2007 study by Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada (PSFC), Towards Effective Tobacco Control in First Nations Communities, these domestic products can be purchased on reserve for between $30 and $35 a carton. The founder of one such company, Grand River Enterprises (GRE), was recently acquitted of charges of trafficking contraband cigarettes in the United States; similar charges against other company executives are still pending.

Native Canadians are entitled by law to purchase a certain amount of legal products exempt from federal and provincial sales taxes as well as provincial excise taxes, as guaranteed by section 87 of the Indian Act. There is also little enforcement of the requirement for status Indians to pay federal excise taxes on reserve. These “tax-free” purchases are then illegally resold without tax to non-Aboriginal customers, either in on-reserve smoke shacks or, increasingly, by criminal gangs off reserve.

Native Canadians are entitled by law to purchase a certain amount of legal products exempt from federal and provincial sales taxes as well as provincial excise taxes, as guaranteed by section 87 of the Indian Act. There is also little enforcement of the requirement for status Indians to pay federal excise taxes on reserve. These “tax-free” purchases are then illegally resold without tax to non-Aboriginal customers, either in on-reserve smoke shacks or, increasingly, by criminal gangs off reserve.

In its 2008 report, the RCMP estimated the number of organizations involved in the contraband trade at 105. Sixty-nine percent of those groups were also involved in drug and/or weapons trafficking, while 30 percent of these groups had “violent tendencies.” Profits from contraband cigarette traffic have even been linked to terrorist organizations, including Hezbollah. In 2010, the RCMP estimated that 175 criminal groups are involved in the trade.

In the past few years, the contraband trade has grown so rapidly in Ontario that “it undermines all other efforts to reduce tobacco use, especially among young people,” according to Building on our Gains, Taking Action Now, a report published in October 2010 by the province’s Tobacco Strategy Advisory Group (TSAG). A study published in the same month in the online journal Tobacco Control, by researchers Russell Callaghan, Scott Veldhuizen and David Ip of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) and the University of Toronto, revealed that 43 percent of the cigarettes consumed by teenage smokers in Ontario were contraband, up from an estimate of 25 percent in the 2006-07 Canadian Youth Smoking Survey. Meanwhile, a 2008 report by PSFC, Estimating the Volume of Contraband Sales of Tobacco in Canada, updated in April 2010, found that the overall number of cigarettes sold in the Canadian legal market declined by more than 25 percent between 2002 and 2008. At the same time, PSFC reports that the number of smokers remained virtually the same over that period. Contraband appears to be filling in the gaps: according to data compiled by PSFC and the Canadian Tobacco Manufacturers’ Council, fully 30 percent of cigarettes smoked in Canada are contraband.

This is not the first time Canada has witnessed an explosion of contraband tobacco activity. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a number of cigarette manufacturers shipped cartons of their products to the US labelled “for export,” to avoid tobacco taxes on products for domestic consumption. Smugglers then brought these cigarettes back into Canada, chiefly through Akwesasne. Contraband sold for half the price of legal products; by 1994 it was estimated that it held up to 60 percent of the market in Quebec and Ontario. The federal government sued cigarette manufacturers over their role in this scheme; over the past few years, the companies all pleased guilty or settled these cases, with the most recent settlement producing payment of half a billion dollars in fines this year alone.

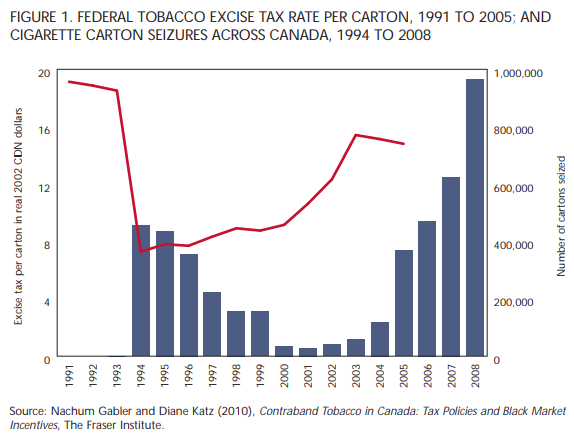

What inspired these surges in criminal activity? Researchers Nachum Gabler and Diane Katz, in Contraband Tobacco in Canada: Tax Policies and Black Market Incentives (2010), point to changes in tax policy by federal and provincial governments. Between 1985 and early 1991, in an attempt to curb smoking rates, the federal government increased its excise tax by 107.3 percent, from $6.01 to $13.06 per carton (all figures real 2002 dollars). In 1991, the tax rose again, to $19.14. During the same period, national contraband seizures increased dramatically, hitting a high of 456,333 cartons in 1994.

In response, that same year Ottawa cut the tax to $7.29. By 1997, the number of cartons seized had declined to 222,228. Until 1999, taxes remained relatively low, but then they started rising again and by 2001 were over $10 per carton. In 2001 and 2002 a series of tax increases designed to curb smoking rates hiked the tax per carton to $15.85.

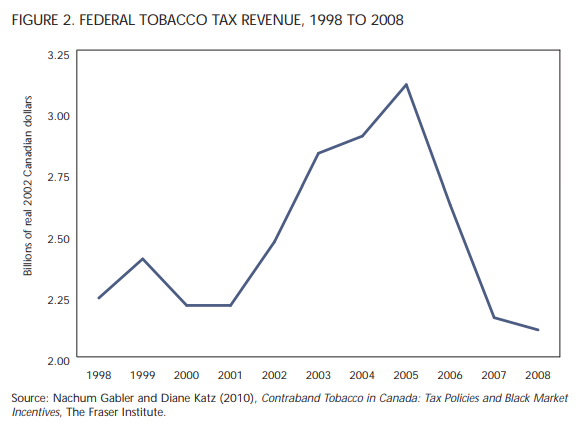

Since then, the federal government has continuously increased the tax to maintain an approximate levy of $15 in real 2002 dollars. Provincial governments have also enacted tax increases in varying amounts, the highest in Ontario, the lowest in New Brunswick. Over the same period, the number of confiscated cartons of contraband skyrocketed, from a mere 28,996 seizures in 2001, to 39,773 in 2002, to 119,968 in 2004, to 965,688 in 2008 (figure 1). High taxation of tobacco products is designed to achieve two goals: make money for the state, and discourage consumption to improve public health. For years, it managed to achieve both. Governments reaped huge profits from the sale of cigarettes, compensating for declining consumption through higher rates. In the last few years, however, increased contraband trade appears to be eating into government receipts (see figure 2).

In terms of smoking reduction, there is clear evidence that high taxes discourage smoking, particularly among economically disadvantaged groups such as young people. According to the American Lung Association, every 10 percent increase in the price of a pack of cigarettes reduces youth smoking by about 7 percent. A 1994 unpublished draft study by Health Canada, obtained through an access to information request by TSAG, found price was a key factor for young people in deciding whether or not to smoke. They calculated that a 50 percent price reduction in the cost of a pack of cigarettes would cause 355,000 more adolescents to take up the habit over five years, resulting in approximately 40,000 smoking-related deaths before age 70.

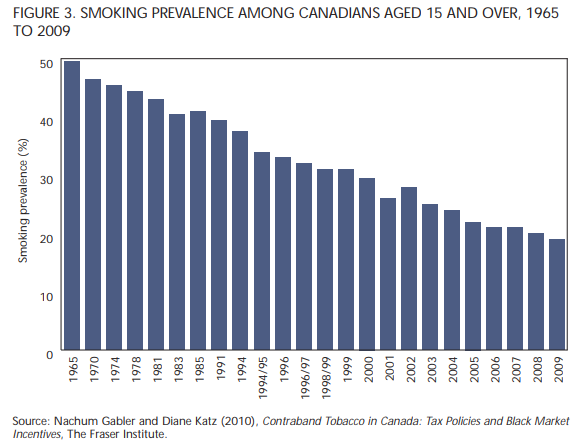

High taxes also discourage the general population from smoking. Gabler and Katz’s research shows that periods of rapid tobacco tax increases in Canada coincided with a considerable decline in smoking levels for all age groups. As can be seen in figure 4, reproduced from their report, until the federal government reduced the tobacco tax in 1995, the number of smokers dropped by 16 percent over a 10-year period. A 10 percent increase in the price of tobacco products is estimated to reduce lawful cigarette sales by between 3 and 10 percent.

Katz, who is now a research fellow with the Heritage Foundation in the US, agrees that high taxes lower smoking rates — to a point. “What we found,” she said “is that there is an impact on raising taxes and lowering levels of smoking. There is also dramatic evidence that raising taxes increases the incentives for a black market. When dealing with a population of smokers that seems to be bent on smoking, the prevalence rate does not go down in dramatic fashion. What you are left with is a hard-core population that responds to the second incentive.”

It appears that in Canada, that situation may have arrived, as the decline in smoking rates has stalled — and may even be reversing itself. According to Gabler and Katz, between 2001 and 2008 the sale of legal cigarettes declined more than the smoking rate: 31 percent vs. 25 percent. In his series “The New Big Tobacco,” published in September 2010 in the National Post, journalist Tom Blackwell writes, “The percentage of Canadians who used tobacco plummeted from close to 50% of adults in the mid1960s to 19% by 2005, but has stayed more or less the same for the last four years. Among people aged 15-19, rates fell from 25% in 2000 to 15% in 2006, then also flattened out…the proportion of daily smokers in Grades 10-12 jumped slightly in the 2008-09 school year from the year before.”

The relationship between high taxes and contraband is not unique to Canada. One has only to look south of the border to see its effects, in the form of interstate tobacco smuggling. The US federal government has imposed a tobacco tax since 1862, while the first state tax was implemented by Iowa in 1921. As of 2005 all 50 states imposed a range of taxes, and some municipalities such as New York City and San Francisco also impose local taxes.

More recently, in 2009 the American federal government increased its excise tax from 39 cents to $1.01 per pack. When the rate hike was announced, Washington estimated that the sale of tax-paid cigarettes would drop by about 10 percent, or 1.7 billion packs, in the following year. But it also anticipated an increase in criminal activity, as evidenced by the US Congress’ passage of PACT, the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act, which took effect in June 2010. PACT enacted tough new measures to curtail inter-state trafficking, including banning the US Postal Service from delivering tobacco products.

Also in 2009, the state of Arkansas passed novel legislation that implemented a lower, variable tax rate for towns and stores located near state borders. While it doubled its tobacco tax from 59 cents to $1.15 per pack, it also provided that within 300 feet of the state line, and wherever there are two adjoining border towns, the cigarette tax on the Arkansas side is required to be equal to the cigarette tax of the neighbour state plus 3 cents, as long as this is not greater than the Arkansas rate. These “low-tax” zones are designed to decrease the incentive for smuggling; their effectiveness has yet to be evaluated.

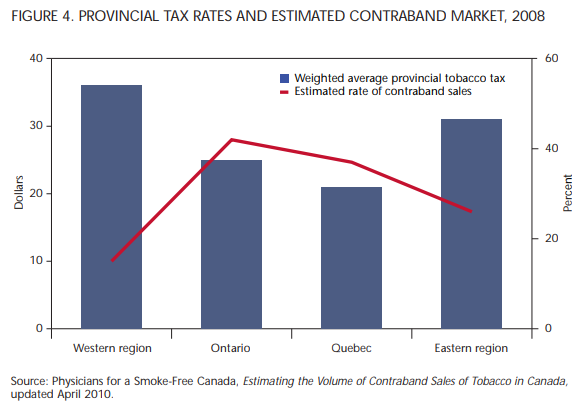

Still, research by many Canadian antismoking activists disputes the link between tax increases and criminal activity. Among these are PSFC: as can be seen in figure 3, from its 2008 report, there appears to be no correlation between provincial tax rates and the estimated contraband market in different regions of Canada.

Michael Perley, a member of TSAG and director of the Ontario Campaign for Action on Tobacco, also refutes the notion that high taxation automatically contributes to increased contraband activity. He points out the fact that the provinces with the highest level of contraband trade also have the lowest and third-lowest price per carton: Quebec and Ontario, respectively. “The highest price is in the Northwest Territories, and all western provinces are at least $10 a carton higher. Nova Scotia is over $20 a carton higher. Yet Ontario and Quebec have this contraband problem. If it was simply because of higher taxes, then we should see massive contraband problems in western provinces, but we don’t.”

But other experts have a different explanation for the inconsistent relationship between tax levels and contraband trade in Canada. According to Katz, geography is the real reason for the difference between contraband activity in western and central Canada. “You see it [contraband] more in Ontario and Quebec because of the reserves nearby and the ability to smuggle at the border, which is not the same as out west. But you are beginning to see more contraband out west, coming from China.”

Political scientist Tom Flanagan of the University of Calgary is the author of seven books on Canadian Aboriginal issues. His most recent work is Beyond the Indian Act: Restoring First Nations Property Rights, where he addresses legislative impediments to building sustainable economies on Native reserves. Flanagan emphasizes history and culture as the reasons behind the concentration of the contraband trade in Quebec and Ontario, centred on the Mohawk reserves.

“There is a special problem with Mohawks,” he says. “One is the crossborder set of reserves and another is their unique views about sovereignty, which are much more aggressive than any other First Nations…They are drawn to smuggling because it allows them to symbolize their disdain for Canadian and American law.” He adds that, ironically perhaps, “the Mohawks are the most economically sophisticated First Nations groups in the country, at least in terms of personal participation in the workforce…and have been in the vanguard in Canada in producing highly educated professionals.”

Flanagan’s analysis is echoed by observations in PSFC’s 2007 report, which chronicles the history of the Native tobacco trade in Canada, and the extent of innovative approaches such as tax-sharing agreements between Native bands and provincial governments. In Quebec, it notes that unfortunately such an arrangement “is not recognized by the Kahnawake Tobacco Association which carries on tobacco trade on Kahnawake without regard to the agreement between the Quebec government and the [Mohawk Council of Kahnawake],, asserting their aboriginal right to do so.”

While researching the issue of contraband tobacco, Blackwell encountered a similar defiant attitude when visiting several Quebec and Ontario reserves. In his National Post series, he quotes Chief Bill Montour of the Six Nations Reserve as saying, “I look at the tobacco industry as the basis for a diversified economy for the Six Nations.” A local smoke shop owner, Edna Holyome, added, “Tobacco is our natural resource.” Meanwhile GRE is actually suing the federal government for more than $500 million in taxes paid since 1977, claiming that Ottawa has failed to take action to shut down nonlicensed competitors.

The Aboriginal cigarette industry, both legal and illegal, is also bringing prosperity to Native communities. Blackwell reports that in Kahnawake, it is estimated that 800 to 2,000 of the reserve’s 8,000 residents are employed in tobacco. Weekly wages for factory workers average $600 to $700, tax free, with some plants paying bonuses of up to $10,000 a year. At the upper end of the spectrum, factory owners pour millions of dollars into on-reserve McMansions and redirect hundreds of thousands of dollars in profits to community projects.

“I wouldn’t call it all negative. If you put aside the nature of the business, it has had positive economic impact on four reserves in Ontario and Quebec. It has clearly generated a fair bit of wealth and prosperity, people are earning more money, there is more development,” Blackwell observes. “At the same time, some people that are getting in to the tobacco business did have other jobs: a guy who ran a construction company told me a number of his employees had quit to go work in the tobacco industry. You could argue that’s not positive if they’re leaving a legal, productive business to make or sell tobacco.”

This has caused tensions within Aboriginal communities with those who do not share in this wealth, and those who oppose the tobacco trade as inconsistent with Aboriginal ideals and long-term community development. If young people can earn an easy living in the tobacco trade, particularly contraband, it could discourage them from pursuing more stable — and legal — employment.

While the tobacco trade may boost some incomes on reserve, it also impoverishes businesses off reserve, such as convenience stores that depend on tobacco consumer traffic to drive sales of other products. According to the Canadian Convenience Store Association, in 2009 close to 2,300 family-owned convenience stores, mostly in Ontario and Quebec, went bankrupt due to the growing black market.

The government’s response to the contraband problem to date has been mostly in the area of law enforcement. The goals of the RCMP’s 2008 strategy were to disrupt organized crime groups involved in illicit tobacco activities, enhance intelligence gathering and “increase public and law enforcement awareness.” According to an RCMP progress report published a year later, however, it is apparent that very little has been achieved. The report highlighted some high-profile successes, such as surge operations in Ontario that increased the price of contraband from $170 to $300 a case and Project Chateau, the disruption of a major contraband network involving the Hells Angels in Quebec. But it concludes, that “The RCMP recognizes that there remains considerable ground to cover in implementing the Strategy and reducing the impact of illicit tobacco on Canadian society.”

In May 2010, the federal government announced a series of initiatives to boost the fight against contraband. These included the establishment of a Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit Contraband Tobacco Team by the RCMP, the creation of a Detector Dog Service by the Canada Border Services Agency in Montreal and Vancouver, and the development of a multimedia awareness campaign about the negative impact of contraband, by Revenue Canada.

But critics say some of these measures, such as the sniffer dog squad, will make little difference. They call on both the federal and provincial governments to do far more. Perley applauds the efforts of Quebec, which “as of 2005 has made it illegal to ship raw leaf tobacco to anyone who does not have a provincial permit to manufacture cigarettes. They have made a number of seizures.” Perley would like authorities in Ontario to have similar enforcement powers, to ensure that the sale of raw leaf tobacco is more tightly controlled.

“Let’s give municipal police officers permission to give a ticket right on the spot, and confiscate contraband.” TSAG’s 2010 report also recommends empowering all levels of police to seize vehicles used for the transport of contraband.

Governments have also attempted to tackle the problem by enlisting the participation of Aboriginal bands through tax-sharing arrangements. The goal is to discourage contraband by having Native bands benefit from tax collection, since the proceeds are returned to their communities. Currently, a number of Aboriginal bands in PEI, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec, Manitoba and BC have such arrangements with their provincial governments.

The structures of these agreements vary. New Brunswick currently has a tax-sharing agreement with Native bands, whereby 95 percent of provincial taxes collected on sales of tobacco to non-Natives is remitted to the community. The province also allows only tobacco purchases by First Nations that are delivered to a reserve to be exempt from the GST and the provincial portion of the HST; off-reserve purchases of tobacco do not qualify for the exemption.

Manitoba also has a tax-sharing agreement, whereby provincial tobacco taxes are collected on all tobacco sales on reserves. The funds are remitted to the provincial government, which then remits them to the bands, minus the taxes collected on sales to non-Aboriginals buyers.

In accordance with an agreement with the federal government, some bands also impose their own “First Nations Tax” equivalent to the GST. Eleven bands in British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Manitoba currently charge such a tax, the proceeds of which return to the community.

Provinces also have different means of controlling the number of tax-free cigarettes purchased on reserve. The 2007 PSFC report recommends working with Aboriginal communities, and expanding an improved version of Alberta’s policy on the purchase of tax-free cigarettes to other provinces. Such a system would oblige retailers to pay the tax and then seek reimbursement for tax-free sales. It would provide all on-reserve retailers, free of charge, with electronic transaction equipment and an obligation to use it. The idea would be to incentivize compliance and minimize the availability of tax-free cigarettes to non-Aboriginal buyers.

But apart from the tax exemption for Aboriginal Canadians, which is enshrined in the Indian Act — and enables the contraband trade — the relationship between Native Canadians and the federal government also creates other incentives for illegal activity. It is no secret that poverty constitutes a breeding ground for crime, and that Native reserves have some of the worst social and economic conditions in the country. This is the result of many factors, one of which, according to Flanagan, is a lack of property rights, which impedes wealth creation. “It’s difficult for all Indians to make their highest and best use of their land because of the property rights structure created by the Indian Act. First Nations don’t own their own lands individually or collectively. Development always requires multiple levels of approval: band council, department, the minister and his officials. This is slow and adds a lot of additional costs, so a lot of potentially profitable things never happen. Members of First Nations lose sources of income that they might have had if their land could have served as the locations for shopping centres, factories, office buildings, apartment buildings: sources of revenue for ground rent and [for creating] jobs and careers.”

In Beyond the Indian Act, Flanagan proposes new legislation to set up an alternative land ownership regime First Nations could opt into, to receive collective ownership and the right to create private ownership and title. It is modelled on the Nisga’a Agreement, which took effect in 2000 and is allowing that community to create private title for 400 owner-occupied lots.

Knowing all this, where can we go from here? Current government policy is to maintain high tobacco taxes to discourage smoking. While this will discourage the smoking of legal products, it also encourages the consumption of illegal, untaxed products. These products are supplied by a contraband industry that creates an atmosphere of lawlessness and feeds other criminal enterprises. This industry involves Aboriginal Canadians to a large degree, but also gangs and even terrorist groups. Responding to this threat requires increased law enforcement efforts and political will to challenge First Nations authority, neither of which is a financially or politically palatable option for governments.

Maintaining this policy comes with both quantifiable and unquantifiable costs. The direct financial cost presented by a contraband industry to governments is that of lost tax revenue and increased police action. The cost to the private sector is in lost business, to both tobacco retailers and manufacturers. These can all be, and have been, measured.

There is also an opportunity cost, more difficult to quantify, but still very real. When government resources are directed to one objective (such as fighting contraband), by necessity they must be either diverted from another objective (such as health or infrastructure spending), or funded by an increase in taxes. Either way, money that would have been deployed elsewhere in the economy is now consumed by the battle against contraband.

Other costs are less possible, if not impossible, to quantify, but also very real. Damage to a society’s sense of law and order, the proliferation of criminal activity and the increase in crimes such as gun and drug trafficking, not to mention funding terrorist groups, all take a high civic toll. So does the creation of a mentality among Aboriginal communities that their economic future lies in producing bootleg cigarettes instead of starting legitimate businesses.

Of course, a high-tax regime also comes with benefits, chief among which is discouraging smoking, by pricing legal products out of reach. This is both a health and a financial benefit to society. In a country with a publicly funded health system, all citizens bear the costs of treating diseases caused by smoking, even if these costs are partially offset by revenues from tobacco taxes. In Ontario alone, the TSAG study estimates these costs at $1.6 billion in annual direct health care costs, $4.4 billion in lost productivity, and at least 500,000 hospital days.

If illegal products become too prevalent, however, this could start to counter the effects of the tax, as well as reduce the amount of tax collected. While the effects may not be uniform across the country, this appears to be a function more of geography and history than uniquely of economics.

More controversial, but undeniable, are the tangible benefits to the producers, marketers and consumers of contraband product. The contraband tobacco industry creates jobs and wealth for Aboriginal individuals and communities and for a select group of farmers who grow tobacco leaf and sell it under the table for many times its value, as well as for non-Native middlemen who sell the product off-reserve. Cheap cigarettes also mean smokers pay less to feed their habit, leaving them more money for other things; to persons of low income, this is not an insignificant advantage.

Since it is governments that both impose taxes and enforce the law, it is they that have the power to act to change this situation. They must weigh public health outcomes against the cost of criminal activity. It is not a politically palatable choice, for the reasons previously outlined, but it must be confronted. Allowing this situation to fester constitutes an abdication of the state’s responsibility to its citizens.

Governments have several options open to them on the tax front: maintain a high-tax regime and engage in an ever more expensive war on contraband; lower taxes with the expectation that contraband activity will naturally decrease, but risk an increase in the smoking rate; lower taxes and step up enforcement and anti-smoking awareness campaigns, to try to mitigate this risk; engage Aboriginal communities in strategies such as revenue sharing, in the hopes that self-policing will stamp out criminal activity; create low-tax zones such as those in Arkansas in an attempt to starve the contraband trade on reserves; or a combination of the above. Purchase of tax-exempt products could also be improved, following the recommendations of PSFC.

Manipulating tax levies and stepping up law enforcement against contraband are of course not the only means of lowering the smoking rate. Over the past two decades, public awareness campaigns, advertising bans and graphic warning labels all served to erode the allure of smoking. Social norms and trends toward healthier lifestyles compounded this effect; smoking is no longer as “cool” among young people, and their baby boomer parents have increasingly butted out in an attempt to extend their own lives. It is also much more difficult to practise a smoking habit; even outdoor venues, such as restaurant patios, are increasingly off-limits.

Arguably, a reduction of taxes on cigarettes may be less likely to increase the smoking rate today than two decades ago. It would be worth repeating earlier studies, such as the unpublished research that was conducted in 1994 by Health Canada, to determine if conditions have changed, especially with regard to young people, in order to help guide the government’s choices in future tobacco tax policy. It would also be worth the government’s while to engage citizens in the war against contraband, through a targeted public awareness campaign. The current government has promised such a campaign several times, including in its announcement in May 2010, but, as of this writing, has yet to deliver it. Blackwell sums up the state’s dilemma: “I think at some point [reducing taxes] would have an impact as it did after the first round of contraband smuggling back in the 1990s, but the concern is on the part of the public health community that you do that and basically increase the demand for the legal product. It would restore market share to legal tobacco manufacturers but not achieve public health goals.”

Whatever government decides to do, one thing is clear: inaction is not an option. Governments cannot allow criminal enterprises to proliferate unchecked, nor can they ignore the health risks presented to young people by the increased contraband trade. Something has to give, and the most effective tool at their disposal, like it or not, is the tax system.

Perley maintains that lower taxes are not the answer, but law enforcement and public awareness are. “It’s not a demand problem but a supply problem. Governments, both federal and Ontario, have yet to take significant action. Let’s give municipal police officers permission to give tickets right on the spot and confiscate contraband. Let’s empower all levels of police to seize vehicles. [Let’s make sure] raw leaf tobacco goes only to people licensed to make it. And do public education.”

Flanagan disagrees. “There is no solution but lowering the tax. I don’t think vigorous law enforcement is possible…To really attack it would almost be a military solution, and the Mohawk would fight back. The Canadian public would not put up with the violence — it would be like another Oka standoff, which basically the Mohawks won.” He adds, “Any heavy handed enforcement is likely to touch off sympathy blockades on a wide scale…in theory the law should be enforced, but in reality Canada doesn’t have the resources to control all the rail lines and road and power lines across the country — if the First Nations put their mind to it, they can cause a lot of damage in places where there are no police to keep an eye on it.”

Katz also leans toward lowering taxes, but acknowledges the decision is a tradeoff. “You have to weigh whether you are getting enough of a reduction in smokers compared to the effects of the black market — or do the negative consequences outweigh the positive?” Like Flanagan, Katz also points to “the elephant in the room. The whole problem also reflects government’s unwillingness to confront the issue of autonomy on the reserves.”

Whatever government decides to do, one thing is clear: inaction is not an option. Governments cannot allow criminal enterprises to proliferate unchecked, nor can they ignore the health risks presented to young people by the increased contraband trade. Something has to give, and the most effective tool at their disposal, like it or not, is the tax system.

This means that, to fight contraband, government will have to cut taxes to some degree. Otherwise, law enforcement efforts will be the equivalent of a Sisyphean rock: push it uphill, and market forces will simply roll it down again. Cutting taxes may slow the decline in smoking rates, but since the contraband trade appears to be doing the same thing, governments have little to lose by striking a better balance between taxation as a disincentive to smoking and as an incentive to criminal activity.

Government must also balance other policy considerations, including public health and Aboriginal issues. Discouraging smoking dependency is a legitimate policy goal, particularly in a country with a publicly funded health system that treats the illnesses caused or compounded by tobacco use. The state should also not simply remove the underground cigarette economy from Aboriginal reserves without replacing it with legal avenues for opportunity. Empowering First Nations with the tools for a solid economic future is the long-term solution to ending the contraband tobacco trade. It should be a priority for all governments to make real progress on this issue.

Photo: Shutterstock