One of the architects of Liberal social policy in the governments of Lester Pearson during the 1960s was the influential policy thinker Tom Kent. His ideas later lost favour for a number of years, but today, as issues of social and economic equity are again topics of public debate, they deserve new attention.

In September 1960, Kent delivered a landmark policy paper at a meeting of academics, politicians, business people and trade unionists at Queen’s University. The meeting later acquired semi-mythic status as the “Kingston thinkers’ conference.” More formally, it was the Study Conference on National Problems, held under the auspices of the Liberal Party, although part of its rationale was that it was not a party policy meeting; such a meeting was to follow a few months later. Kingston was to be a nonpartisan brainstorming session, organized by the former civil servant Mitchell Sharp at Pearson’s behest, after his election as party leader in 1958. Encouraged by friends and advisers, including the nationalist Walter Gordon, the historian and intellectual Frank Underhill and Kent himself, Pearson sought to make the Liberal Party liberal with a small “l” as well as a large one. For that reason, and because the conference promised to be dominated by policy wonks rather than politicians, it was regarded with suspicion by the party’s old guard.

Kent was an English immigrant who had taken on the editorship of the Winnipeg Free Press six years before, at the age of 32. He had previously worked at Bletchley Park, the British government’s decryption centre during the Second World War, and then on the staff of the Manchester Guardian and as assistant editor of the Economist. By the early 1950s he felt ideologically rootless, as he recalled later in in his candid memoir, A Public Purpose: An Experience of Liberal Opposition and Canadian Government (1988). He fully supported the emerging welfare state but was at odds with what he described as the Labour Party’s “devotion to public ownership as a dogma rather than a device for special circumstances.” The Conservatives had nothing to offer, and both parties were entrenched in “Little Englandism,” refusing to recognize the need to “join Europe,” which Kent saw as the only way in which Britain could recover some of its former strength and stability.

Canada offered the prospect of change and renewed public engagement. In Winnipeg he won a reputation as a worthy inheritor of the mantle of John W. Dafoe, the famous editor who had made the Free Press one of the leading newspapers of the country earlier in the century. Already having been impressed by Liberal politicians, including Pearson, while in London and on visits to Canada, he was quickly drawn into the Canadian Liberal establishment. He grew especially close to Pearson during the Suez Crisis of 1956, when the Free Press supported his diplomatic initiatives at the UN, seen by many others as a betrayal of Canada’s historic attachment to Britain. Kent became critical of the government of Louis St-Laurent in its last years and was well placed to take part in the party renewal that followed the Liberals’ defeat, then humiliation, in the elections of 1957 and 1958. Any hesitation he may have felt as an editor participating in partisan politics was removed when he resigned his position in 1959.

As he became more involved in the Liberal Party, he emerged as an influential member of its left wing and played a significant role in turning it into an instrument of social democratic reform in the 1960s. His contribution at Kingston — a long paper somewhat grandiosely entitled Toward a Philosophy of Social Security — marked a major development in this realignment of priorities. Along with another paper, by Maurice Lamontagne on economic policy, it was the chief reason why the conference acquired the reputation it did.

Kent thought it necessary to think about first principles, because postwar prosperity had created different conditions than those of the Great Depression and the Second World War that had underlain most of the social welfare measures already enacted. These, in any case, had been ad hoc, and there was a need to determine a more systematic basis for policy. He offered his audience a definition and a rationale for social security. “In general,” he said, it was “the provision by the state of income to various groups of people who cannot earn an adequate standard for themselves,” and its roots lay in “the ethics of human solidarity.” Its purpose was only in part to be a “social safety net”; primarily, it was an instrument of human development.

No utopian idealist, he argued that government action was called for not only because it was right to help others but because social change had made modern life collective in nature and consumption was necessarily a collective endeavour, whether in education, health care, housing or regional development. When critics complained of government action as restricting freedom, they were thinking of freedom only in negative terms, as the absence of coercion. Their logical standard was the life of a hermit. Kent believed in positive freedom: we are free because society, acting together, makes us free. For those unable to help themselves, the role of government was to assist in providing opportunities to share in the freedom of all. “The philosophy of social security,” he said, summing up his reflective introduction, “is an equalitarian philosophy.”

Kent offered Liberals a way of thinking creatively and comprehensively about social security, and the Kingston conference as a whole energized those who attended, bringing many of them into the party for the first time. Some went on to attend the Liberal policy meeting called the “National Rally” in January 1961. With Walter Gordon acting as policy chair and Kent as chief drafter of resolutions, the rally endorsed many of the ideas of Kingston and gave the party a new reformist orientation. Over the next decade, first as Pearson’s policy adviser, then as his chief of staff after the Liberals took office in 1963, and subsequently as deputy minister in two different departments, he helped to put in place a set of policies that laid the foundation of the Canadian welfare state: a national health plan, contributory old age pensions and a role for the national government in areas of nominally provincial jurisdiction, like education and social welfare.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Liberals came to regard the Kingston conference as a talisman of party renewal, yet similar meetings held after later setbacks had no comparable impact. Kingston was very much a phenomenon of its time. For one thing, the intellectual context was distinct. Public opinion had shifted in favour of greater collective responsibility in the aftermath of war and depression, and it was the old-guard Liberals — those who resisted Kent in the interests of private enterprise and the sanctity of the individual — who were out of step. The idea of expanding social services was in the air.

The same could not be said of the 1980s, and in the ’90s Kent became increasingly unhappy with his own party, which turned away from its recent history and embraced the neoliberalism of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. He reacted especially against Paul Martin’s budget of 1995, which dismantled many of the gains made earlier. The federal government’s reduction of funding for health care, post-secondary education and social services not only damaged programs but broke faith with the provinces, making future federal-provincial cooperation even more difficult than it normally was.

The institutional context also changed. The tax system was modified in ways that limited national action. In the 1970s, much to Kent’s dismay, Pierre Trudeau’s government turned over some of its sources of revenue to the provinces in the form of tax points, because previous cost-sharing arrangements for programs delivered at the provincial level had deprived federal politicians of any visible responsibility. Why levy taxes for measures you won’t get credit for? Provincial cost-sharing was discredited and the federal government’s leverage reduced.

In response, he sought ways of restoring the integrity of programs he had helped to initiate, and of building on them in ways appropriate to modern conditions. Though he left the federal government in 1971, Kent never really left public policy-making, heading two Crown corporations, chairing a royal commission on newspaper concentration and writing prolifically for policy organizations — he didn’t like the term “think tanks” — until his death in 2011 at the age of 89. He also served as founding editor of Policy Options. At the top of his list of priorities, he placed measures to repair medicare and proposals for the development of early childhood education, what he called “School at Two.”

For all of the change in the intellectual environment at the turn of the century, Kent was skeptical of claims that people had turned against government action in the interests of society as a whole. If there was a growing conservatism, it was because times were hard — jobs were insecure, household debt levels were rising, homes were expensive, the future was uncertain — and the result was greater anxiety and fractiousness. He continued to think that Canadians shared the values of equity and fairness that underlay the reforms of the ’60s.

His belief in the persistence of a sense of collective responsibility has received some support from recent events, notably the NDP victory in Alberta and the Liberal victory federally in 2015. There are also signs that arguments for government regulation of the marketplace have once again become intellectually respectable, in belated response to the global recession of 2008-09. The positive reception of books by progressive writers such as Thomas Piketty and Anthony Atkinson reflects a renewed interest in issues of social and economic inequality, while the Liberal defiance of the deficit taboo in the 2015 campaign received a sympathetic hearing even in the pages of the Globe and Mail Report on Business.

Kent wrote of the Kingston conference that the real challenge of a political party was “to identify the ideas that are right for the times.” The challenge facing politicians who share his outlook today, whether they be in his old party, the Liberals, or in the New Democratic Party, toward which he seemed to be leaning near the end of his life, is to find both the mechanisms and a language that are appropriate to the present, in which to propose and defend the ideas he put forward for national social democratic reform. They will also require some of his patience and intestinal fortitude.

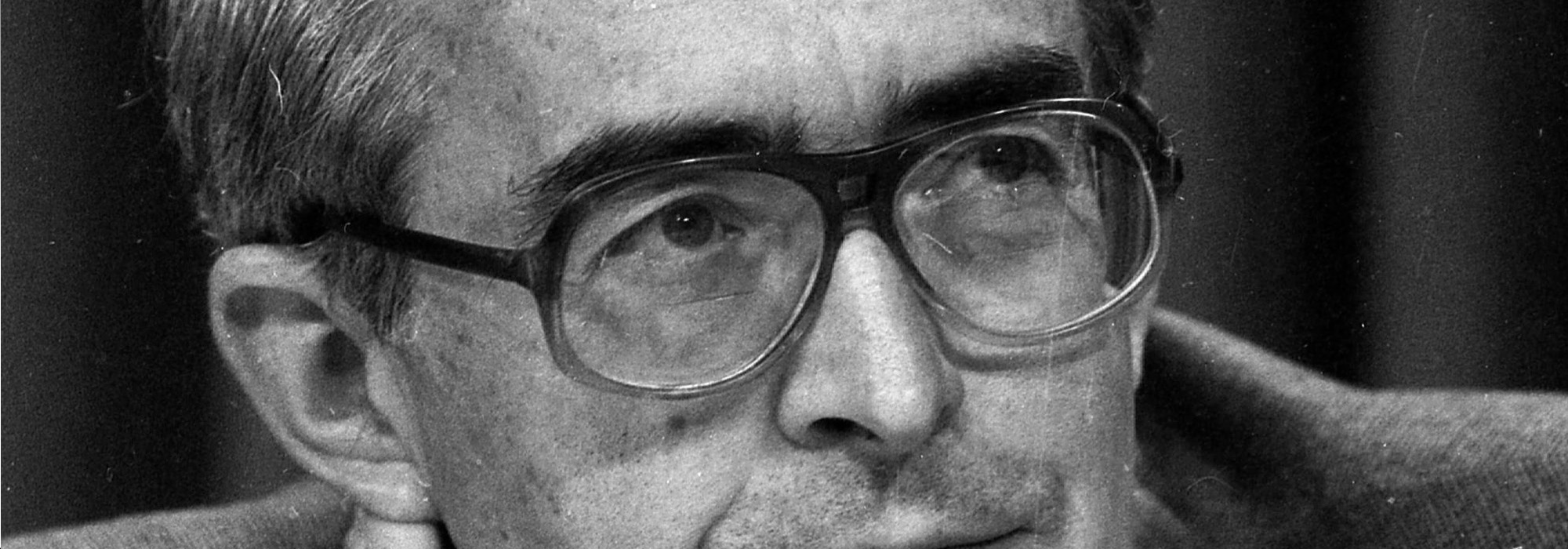

Photo: Tom Kent, who led the 1980 inquiry into newspaper ownership known as the Kent Commission, died at the age of 89. Here Kent is shown in a 1981 photo. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Julien LeBourdais.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.