While the special committee on electoral reform continues to study voting systems, 16- and 17- year-olds will be able to cast a ballot in Prince Edward Island’s province-wide referendum on a new electoral system this fall. This is an important plebiscite to follow, not only because it is a referendum that most parties are unwilling to consider at the federal level, but also because 16- year-olds will have a say. Engaging young people in the democratic process is important, because low turnout translates into unequal political representation and influence.

Yes, voter turnout increased during the 2015 general election – it was up a whopping 18.3 percentage points among voters aged 18-24 compared with 2011, according to Elections Canada. Among voters eligible to vote for the first time, the increase was 17.7 percentage points over the previous election. Within this group, the biggest increase was among women voters, an increase of 19.1 percentage points.

And yet even with this astonishing increase, youth voter turnout still remains lower than the national average, and young Canadians eligible to vote have been participating at lower rates than those of previous generations. It’s a familiar problem across established democracies.

Research suggests that the better educated are more likely to vote than the less educated, and Canada is among the countries where this gap is most pronounced, particularly among young people. We suspect the decline in voter turnout is more heavily concentrated among low-income poor youth (a hypothesis Semra intends to test in her PhD).

Not all young people, however, have disengaged from the democratic process to the same extent. Samara Canada, a nonpartisan charity dedicated to improving political participation in Canada, suggests young people are more prone to participate in other activities like boycotts and protests, even if they won’t necessarily turn out to cast a ballot.

While civic engagement is a good thing, there are reasons to worry about young people skipping the vote. Overall turnout will likely be affected in the long term, as young people are less likely to become voters later in life. Empirical studies show that since the mid-1970s youth eligible to vote have been entering the electorate later in life and participating at lower rates than those of previous generations.

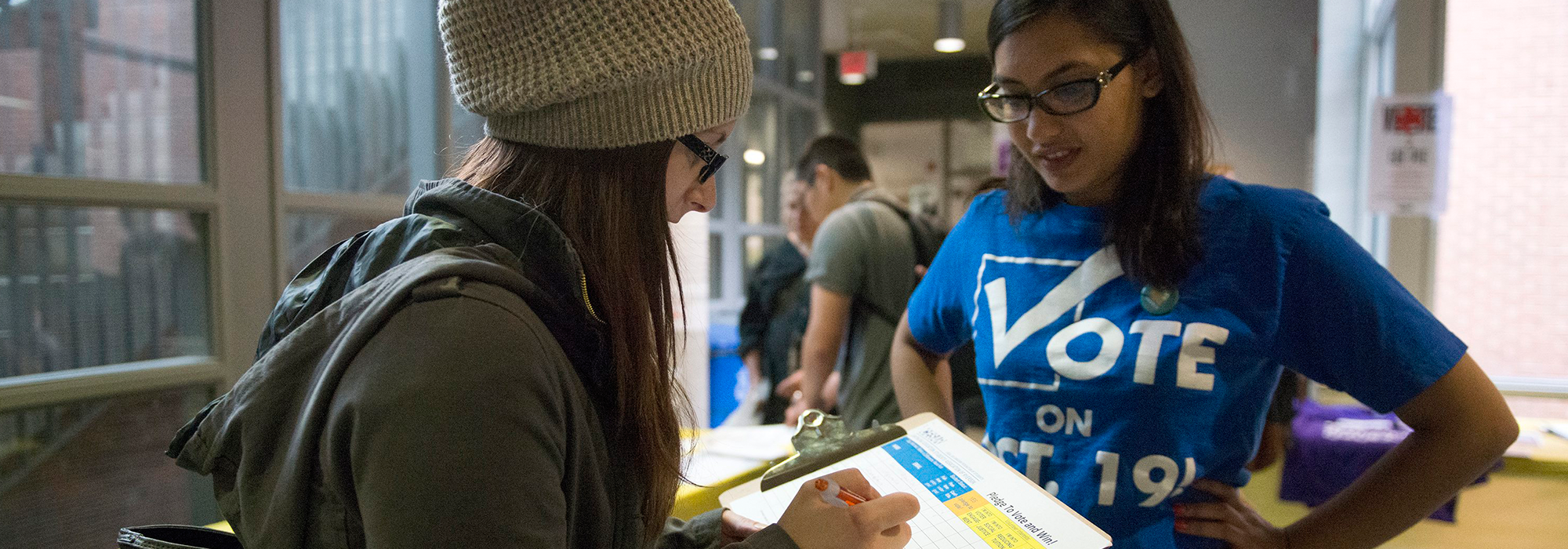

Short of compulsory voting, no electoral system will increase and maintain voter turnout indefinitely. But there are solutions that might make the electoral process more fair and representative of the electorate. For example, data from Election Canada’s National Youth Survey Report show young people are more likely to vote if they are contacted directly by a candidate or political party. Canadian politicians could engage with young people between elections through face-to-face interactions and personalized direct mail. Tuning in and out of politics every four years is not a healthy recipe for a strong representative democracy.

If parliamentarians and the Special Committee on Electoral Reform want to engage youth in Canadian democracy, then they need to include a diversity of young voices in decision-making processes. This would include young people with varying education and income levels, young Indigenous people, women, and youth, from urban and rural communities. There is every reason to believe that people from diverse backgrounds have different views about what voting and elections are about, and it is crucial to pay attention to the various perspectives when it comes to choosing the best electoral system for Canada.

In an effort to engage young students in the electoral reform debates, the Department of Political Science at the Université de Montréal is offering an undergraduate course this semester on electoral systems and options for Canada. It is important to encourage youth participation in a topic as important as electoral reform, as they will inherit any changes that are made. In this course, students will learn about the different electoral systems and vote on the best voting method for Canada. During the first two weeks of class, students were asked to rank the following voting systems: plurality (first past the post), majority (alternative vote), open list proportional representation, single transferable vote, mixed parallel, and mixed compensatory (also called mixed member proportional). Thirty-nine percent voted for mixed member proportional as their first choice. We intend to repeat this vote, along with various others, throughout the course as students become more familiar with the empirical evidence regarding the effects of various electoral systems.

Elections are indispensable for a strong democracy, and unequal participation in the electoral process should be a concern for everyone. Elections provide citizens with the opportunity to express their preferences. Society loses when certain voices are not heard.

Photo: Marta Iwanek / The Canadian Press

This article is part of the Public Policy and Young Canadians special feature.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.