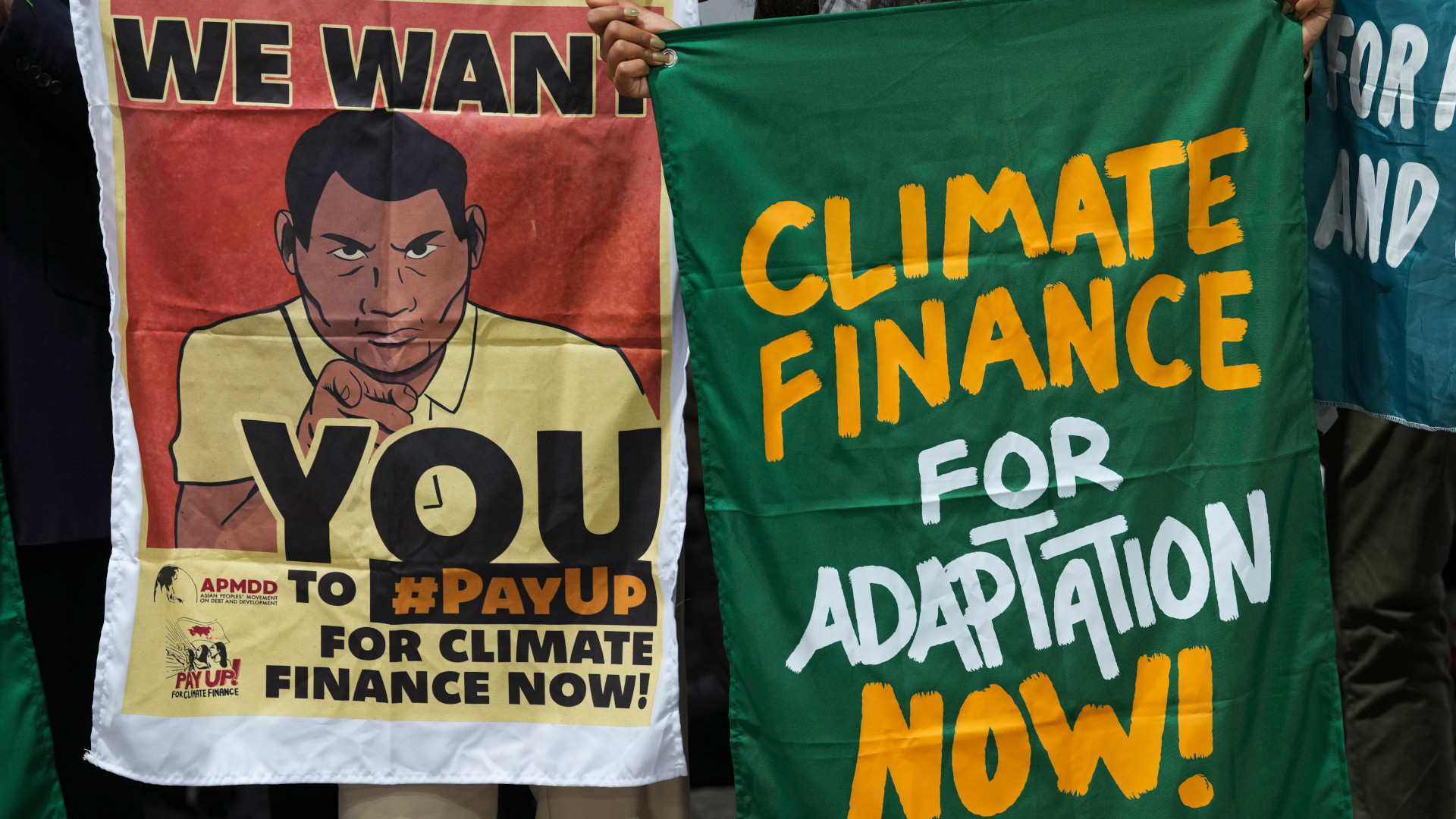

Moral purpose or marketing? This summer, Deutsche Bank became the latest major bank to boycott Arctic resource investment. It’s part of a growing chorus of financial institutions demonstrating their fiduciary responsibility to combat climate change.

At first hand, the announcements look like testaments to global financial institutions finding their “moral purpose.” However, the unfortunate reality is that their Arctic pledges not only fail to contribute to lowering global CO2 emissions or stop the Arctic from melting, but many of those pledges have significant potential to cause damaging social impacts for those who live in the Arctic.

Seemingly a lifetime ago, BlackRock CEO, Larry Fink, published a letter addressed to the world’s global financial institutions about the need to find their moral purpose. In response, annual reporting on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) soon became a standard in financial reporting. At that time, the point of focus for global investors was on the “E” as they set out to demonstrate the many ways in which they are meeting their responsibility to combat climate and environmental changes. A driving sentiment behind many of the efforts has been the notion that if we can save the Arctic from development, we can save the Earth from climate change.

Less than two years following Fink’s letter, the COVID pandemic arrived and as economies fell like dominoes many believed that climate change would take a back seat and with that reporting on ESG. On the contrary, it was soon recognized that companies with strong ESG factors in their portfolios had lower declines in relative terms during the crisis. In a June 2020 webinar, Jim Pass from Guggenheim Partners stated that ESG will not only remain, but we will also begin to see greater emphasis on the “S” in ESG as well. His statements came even before the events in the US that turned the Black Lives Matter movement into a global effort, and propelled the social piece of ESG into the spotlight.

If it is safe to say that the moment of focusing on the “S” – or social – in “ESG” has arrived. It is timely then to set the record straight once and for all about the myth of the Arctic snow globe – an Arctic that can be bottled up and placed on a shelf safeguarded from the rest of the world.

What we are witnessing is that the North American Arctic has become the narrative of convenience for the global investment community.

As climate change science has made evident, CO2 emissions – wherever they originate – impact the entire globe and most drastically affect the Arctic (CO2 travels via the jet stream from wherever it began whether Los Angeles, Mexico City or Saudi Arabia). Thus, to lower the amount of CO2 in the air, the focus must be on emissions at their source, not where they end up.

Yet, what we are witnessing is that the North American Arctic has become the narrative of convenience for the global investment community. It begins with the idea of the Arctic as the bellwether for global climate change, the canary in the coal mine, a vast sprawl of frozen tundra and melting icebergs laden with polar bears, and Indigenous peoples who need to be saved by the world outside.

Barclay’s Climate and Energy Strategy was one of the first financial institutions to declare the Arctic as a place that needs preservation. Its strategy unveils its shift to increase investments in low carbon projects. Yet, it acknowledges that oil and gas will be the main source of energy for decades to come and, “reliance on gas as a transition fuel is expected to increase.” Thus, in the short-term their investments will reflect that reality. After all, citizens need affordable energy to fuel their cars, heat their homes, run their businesses, and grow their economies.

The strategy also discusses its enhanced due diligence process for Arctic projects, which they point out is so stringent that it essentially disqualifies capital investments for these ventures. While the document states that affordable energy is critical for functioning economies and its citizens globally, the same expectations do not exist for Indigenous communities and others who live in the Arctic, climate change there brought about by CO2 emissions elsewhere supersedes their economic aspirations and realities.

With similar sentiments, retailers and shipping companies are making their own announcements. For example, Nike has signed an Arctic Shipping Corporate Pledge to prohibit its products from shipping through the Arctic. However, as the Arctic melts from CO2 travelling North through the jet stream, the most immediate concern should be on existing global maritime shipping though the Suez and Panama Canals which account for about two percent of current global emissions.

Moreover, before the Arctic will be a real viable alternate maritime route for transporting sneakers, the global maritime industry will have long become carbon-emission free. The Norwegians are already using hybrid ships, the Japanese are on their way to finalizing fuel-cell powered container ships and Maersk has committed to net-zero emissions for its vessels by 2025.

Instead, by putting the Arctic in a snow globe, institutional investors are contributing to the ongoing cyclical poverty found in many Arctic Indigenous communities, not least in the North American Arctic. The social impacts of these decisions are concrete. With the front lines of climate change found anywhere from Los Angeles, to Australia, to Greece and the Sub-Saharan Africa, its biggest victims are the world’s poorest communities who lack the economic resources and critical infrastructure to be resilient.

Many North American Arctic Indigenous communities, therefore, continue to remain disproportionately affected by climate change as they are undermined by the legacies of decades long colonization, persisting economic and social neglect, a lack of basic critical infrastructure – all of which results in some of the highest rates of poverty in the OECD.

If, as Barclay’s announcement states, gas development will become increasingly critical during the transition to the global renewable energy economy, why does Arctic gas, then, sit alone in not being able to make its own contribution to the transition? In fact, precedent exists. The Snøhvit project in the Arctic town of Hammerfest, Norway utilizes carbon capture and storage to offset its CO2 emissions.

When institutional investors say no to investments then those communities lose opportunities to become equity owners and grow their own economies and self-sufficiency.

In the case of the North American Arctic, much of the known gas is located in areas that are Indigenous governed and in cases also owned. When institutional investors say no to investments then those communities lose opportunities to become equity owners and grow their own economies and self-sufficiency. After all, Northerners cannot be expected to live on the sale of soapstone carvings alone.

In terms of carbon offsetting, one has to ask whether investing in gas projects in Northern Canada (like Norway did in its own Arctic) could displace coal emissions in China or elsewhere while taking those same Indigenous communities off of imported, premium cost, rationed diesel (a major cause of local CO2 emissions).

These questions need attention and more scientific research. Climate policies coming from major banks and others need to be driven by science, not sentiment.

As institutional investors begin to pivot their focus on the “S” or the “social,” this might be a well-chosen moment to gaze North with an entirely new eye. The North American Arctic needs massive capital now more than ever. There is a critical need for public-private partnerships to invest in projects to build all kinds of critical infrastructure from broadband to ports, roads, hospitals, affordable energy and airports precisely so that more – not less – goods (from food staples to building and medical supplies) can come into the Arctic. These partnerships can also help ensure the Arctic’s breadth and wealth of natural resources (from fish and human knowledge to the minerals required for the global transition to the renewable energy economy) can reach global markets.

The need for increased Arctic investments in all forms of critical infrastructure is just that – critical. It is needed for economic growth and a matter of food security, health, shelter and the life and death of those living there. It is the heart and soul of the “S.” If institutional investors continue to boycott Arctic investment in the name of climate change, they do so at the risk to those who live in the Arctic and the moral purpose underpinning ESG investing.

Photo: Morning light in Frobisher Bay, Nunavut. Photo by Shutterstock/Jeff Amantea.