How to make God laugh? Tell Him your plans. An old joke that would not be lost on the still new and young president of the US, whose transformative agenda was side-swiped by the explosion on April 20 of the BP oil rig Deepwater Horizon that killed 11 workers. The rampant quarrel over the subsequent oil spill threatened as much political damage as environmental.

So it goes for world leaders. Fifty years ago, wily old British prime minister Harold Macmillan languidly counselled another young and untested US president, John F. Kennedy, who asked what were apt to be the biggest problems he could expect, “Events, dear boy, events.”

If the Almighty peeks in on Rahm Emanuel’s early morning staff meetings at the White House, He must chortle to hear Obama’s chief of staff recite his mantra, “No surprises. No surprises.”

There are always surprises. That was the point of presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s TV spot in the 2008 Democratic primary race with the red bedside phone ringing at 3 a.m.

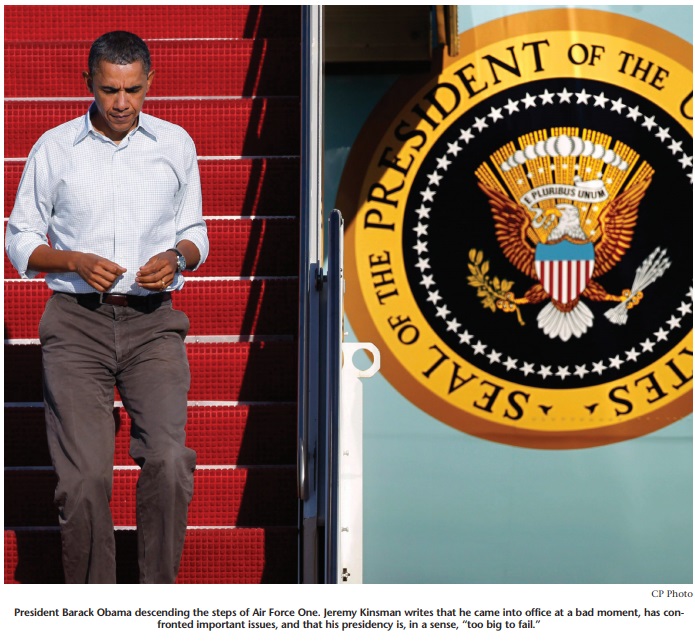

But President Barack Obama seemed as “ready on day one” as any predecessor, even with an “inbox from hell.” Before taking the oath, he brokered an initial economic recovery plan that probably did hold off a depression.

Once in office, he launched and achieved the most ambitious legislative agenda in memory, if not in US history, while fighting two wars.

And yet, his presidency is bitterly contested by a revved-up and uncompromising political opposition that claims to have truer connections to the public’s mood than the cool and sometimes seemingly detached intellectual in the White House.

Obama has laid a foundation for economic recovery but jobs have not rebounded in a way that earns political credit. As David Frum has written, legislation doesn’t count. Presidents earn the big points from “wars won and prosperity enhanced.”

Much of the public remains too jarred by the depth of the economic hit their lives have taken to notice legislation. Bombarded by cable news ranting, they are turned off by the political circus in Congress. The Republicans have fallen back on an American default position of distrust of big plans from Washington.

Yet it is precisely big plans that America needs to tackle its underlying and defining challenges as the leading modern economy and society, and power — still — in the world. If the public could stand back from the fray, the US ought to be relieved it has hired in Obama a chief executive of now demonstrated competence, who has unique and essential gifts for setting out the issues and motivating public commitment to tackle them.

There is no school for US presidents or any sort of life and work experience that can adequately anticipate the job. If there were, Dick Cheney’s CV would have qualified — but for misaligned judgment, and a furtive, dark and offputting personality. A successful political leader needs to be seen as serious and decisive but also needs to project a jaunty sort of confidence, an air of good cheer, such as FDR, JFK and Reagan exuded, seemingly naturally.

Obama has it, and unwavering self-confidence. Jonathan Alter, in one of two remarkable books out this season about him (The Promise; the other is David Remnick’s The Bridge), recounts a converted Bill Clinton crediting Obama with the essential quality a leader of a democracy needs: the ability to convince a myriad of differing people that he “gets” their various situations, even though that he couldn’t possibly have lived through them all himself.

However, timing and tone are everything, and in mid-2009 when the falloff in public support began, these qualities of connectedness seemed missing in a White House too caught up in legislative vote counts on issues affecting Wall Street to be convincingly empathetic on Main Street. While the distracting war in Afghanistan was topping the triage list for emergency repair, right-wing polemics were firing up a populist revolt on economics and governance.

Still, as first terms go, the legislative record alone at a time of dark economic crisis chronicles a pretty remarkable takeoff. Obama’s term looks better at this stage than that of Lincoln, who suffered a disastrous debut military defeat at Bull Run, or of Kennedy, who had to endure a rookie’s embarrassment over the farcical Bay of Pigs invasion. Each had been narrowly elected with a minority of the popular vote, compared to Obama, who is one of only four Democrats ever elected by a majority (joining Andrew Jackson, Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson).

Today, Obama’s approval ratings compare to Reagan’s or Clinton’s at this point. Both of them came back with big second-term wins. Democrats may lose control of the House of Representatives in November’s midterm elections, but that isn’t necessarily all bad news for a Democratic president in the US system, as Clinton showed.

In reality, the 2012 political outcome will be determined by what Obama can do now to coax favour from a very vexed public despite unrelenting opponents. Ominous challenges at home and abroad will include “events” we haven’t even thought of.

Much of the public remains too jarred by the depth of the economic hit their lives have taken to notice legislation. Bombarded by cable news ranting, they are turned off by the political circus in Congress. The Republicans have fallen back on an American default position of distrust of big plans from Washington.

Can he manage the political calculus between recapturing short-term political advantage and the need for longer-term re-positioning of the country? The long-enduring prime minister of Luxembourg, Jean-Claude Juncker, put well the dilemma of political leaders facing the painful necessity of tightening the people’s belts: “We all know what we have to do. The problem is getting re-elected afterward.”

To try to answer, we shall need to look for clues in the Obama record so far, the public mood and the American political divide, and in the man himself in the light of his performance.

But first, let’s consider the Gulf of Mexico oil spill disaster, where many found his leadership wanting.

The oil gushing into the deep sea from the broken rig was horrible news at every level. Politically, there is nothing worse than a crisis a leader can do nothing about. Malia Obama’s question, “Did you plug the hole yet, Daddy?,” defined the issue. Of course, only BP had the means to stop the leak, and until it happened, Obama would be paying a price.

Most of the US public saw BP as a villain doing damage to America. BP seemed to live up to the negative image.

This is a corporation that had pumped itself up to become the number two oil company in the world (after ExxonMobil) through cutting costs and also corners on risk. Within a few months in 2005, BP suffered an explosion at its Texas City refinery that killed 15, resulting in identification of over 300 safety violations and $21 million in fines, and a BP mega-rig, the Thunder Horse, almost toppled over in a Gulf of Mexico storm.

Oil companies have a swagger that goes with prospecting and drilling for the resource we seem to need more than any other. But BP’s corporate style, at least at the top, had a special hubris. Its leaders prided themselves on willingness to “do the tough stuff” in tough locales other oil companies shied away from.

Historically, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was first launched as a tool of empire. (Curiously, its first chairman was the Canadian High Commissioner in London, Donald Smith, or Baron Strathcona and Mt. Royal.) Later renamed British Petroleum, then just “BP” as the UK government divested its stake, the company gave the impression it believed itself beyond mere governments altogether.

It took Vladimir Putin’s tough guys to show that assumption didn’t apply to BP’s vast stake in Russia. However, the company seemed unable to extend this experience to a behavioural lesson on how BP should handle itself in democratic America, especially odd since the US accounts for 40 percent of the company’s assets as well as of its shareholders.

BP’s board chairman at the time was Peter Sutherland, a sensible and politically astute Irishman who had been an EU commissioner and the founding head of the World Trade Organization. He essentially fired secretive CEO John Browne in 2007 after he was caught lying about personal relationships in court documents. Sutherland acted not because he cared whether the CEO was gay, but because of Browne’s lack of transparency about risk.

It is ironic that the US media came in the oil spill crisis to portray Browne’s successor Tony Hayward as some kind of Old Etonian upper-class toff, since to any British ear, Hayward’s accent is anything but posh. He sounds like a straightforward state-educated geologist, though his sharp rise to the top of the glamorous exploration and production stream of the company needed the self-confidence of a man used to a winning hand. When he got the big job, he swept the modern art out of HQ, and he promised safety would be the top priority.

But Hayward turned out in the oil spill to be a communications disaster up against first the US media anaconda and then President Obama himself.

BP still assumed PR could change most any game, but this time their spin was lost in the barrage of harsh facts in the water.

We now know from scientists that this is the biggest oil spill in history. But on May 17, the BP CEO stated that the outflow of oil was only about 1,000 barrels a day. In reality it was about 60 times that magnitude. As the evidence mounted, US cable news, especially Anderson Cooper on CNN, ran ferocious daily blasts about an almost incalculable environmental disaster, BP duplicity and irresponsibility, and — of political significance — woefully inadequate US government response.

The White House had at first been handicapped by scant information, especially from the relevant federal oversight agencies allowed, even encouraged, to run down by the preceding administration, such as the Minerals Management Service, which was broken up in May after revelations it had been for years compromised by a cosy relationship with oil companies.

The record shows that Obama was personally engaged in the crisis from the beginning. But as Rik Hertzberg wrote in the New Yorker, he allowed the “opposite impression to take hold.” It was “a failure of governance, not just of public relations.” Initially on the defensive for not reacting forcefully, he then appeared to be overreacting.

It seemed as if it were the media that had goaded him into showing he “could get mad.” He was right to put all offshore drilling in the Gulf of Mexico on hold for six months, but was rewarded by vivid criticism from the “drill, baby, drill” crowd and Republicans for putting drilling jobs at risk. (The House of Representatives approved at the end of July and sent to the Senate a bill setting out new safeguards on deepwater drilling.)

If the public could stand back from the fray, the US ought to be relieved it has hired in Obama a chief executive of now demonstrated competence, who has unique and essential gifts for setting out the issues and motivating public commitment to tackle them.

If the famous Obama luck clicked in at all, it was in the gaffe-prone performance of the hapless Hayward, and in a statement by a Texas Republican that Obama’s stout extraction of a $20billion clean-up and personal damage commitment from BP was embarrassingly anti-business.

Obama’s June speech to the nation, his first from the Oval office, was curiously flat. He did use the occasion to try to rally the public to its senses on the bigger and longer-term issue of reducing dependence on fossil fuels, though he later bowed to the reality that Republican opposition would not allow Democrats in the Senate to push ahead with a significant energy bill.

The BP issue will recede from prominence. At the beginning of August, the leak was plugged at last, and a relief well was nearly in place. The surface oil slick is dispersing by natural maritime processes, and while the underwater plumes are still unresolved, it seems as if the US coast will be spared anything like the extent of damage that had been feared.

Politico.com reports a public disappointed in Obama’s handling of the crisis. But Obama and his team have learned from the experience, especially on the communications side. America’s regulatory safeguards will be strengthened. In the telling, as time goes by, the story may not be a negative for the White House after all.

Still, it is a far cry from the heady days of “change you can believe in” surrounding the inauguration of the first black American president after a succession of white Protestant males since 1776 (with the sole exception of Roman Catholic John Kennedy’s brief thousand days).

If it had been up to whites, they would have chosen as usual — John McCain won their vote, 55 to 43 percent.

But America’s faces have changed. Obama won a national landslide, 53 to 46 percent, because whites are a smaller proportion of the population than they were 50 years ago. Eighty percent of Americans over 65 are white, but only 50 percent of those under 25.

Obama won the election by capturing the votes of independents and of younger and ethnic Americans. There is a 20-point spread, even today, between the voting intentions of those over 50 and those under 30.

In 2008, there were between 15 and 20 million first-time voters and Obama won 70 percent of them.

There are two key questions going forward: Will these first-timers turn out again in the same numbers? And will Obama also recapture a majority of the independents’ vote (38 percent of the electorate), as he did in 2008? Right now, he has slipped among independents, who are concerned about the size and role of government and deficits.

For many, the way Obama hit the ground running before the Inauguration — indeed, even before the election when he personally steered acceptance of the second TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) financial recovery plan — is yesterday’s news.

Obama probably did save the country, and possibly the world, from a depression. His problems coming in were as daunting as any faced by a president. I heard from a Washington insider that when his initial staff meeting right after the election laid out third-quarter 2008 numbers showing a 2 percent job loss, as well as other disastrous economic data and ominous foreign news, the President-elect jokingly asked if it was too late to ask for a recount. But he was always confident he could lead an effort to make things right on the bigpicture priorities of

- nailing down a recovery and stimulus package

- stabilizing the housing market

- starting credit flowing again

- ensuring longer-term investment in energy, education and health care

- reducing discretionary spending

The issue was how to get it all done. Alter reports in his book that Obama knew he had to use his political capital while he had it. But his team made mistakes.

- They were too slow staffing the administration’s key posts, because of over-cautious vetting after nominees for Treasury (Tim Geithner) and Health (Tom Daschle) had tax issues

- They turned over too much ownership on key bills to the fractious process in Congress

- They missed the urgency boat on job creation

- Obama continued to try bipartisanship long after the Republicans had revealed they were working only to oppose his presidency. Despite these weaknesses, the amount that Obama and the Democratic Congress did get done was pretty astounding.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which injected almost $800 billion into the economy as stimulus, was a complex set of interlinked policy instruments with three main parts: tax breaks for the middle class, support for state and local governments on the brink and infrastructure support. Despite Republican opposition from the start, markets responded positively, even if today the public gives the stimulus action little credit on job creation. It may have saved many jobs, but saving doesn’t represent “points on the board” in popular reckoning.

A foreground challenge was the failing car industry. GM and Chrysler were hemorrhaging cash. Liquidation of GM was talked about. But with 225,000 GM employees and over half a million retirees living off corporate-plan pensions, not to mention thousands of dealerships and parts suppliers across the country, Obama judged GM “too big to fail.”

He managed what Alter describes as “the most complex corporate restructuring ever attempted by Washington,” which took a 60 percent stake in GM. Obama fired GM CEO Rick Wagoner, who seemed in complete denial of the situation, but otherwise trusted his task force to appoint new executives to run GM according to sound business principles, which, in fact, enabled GM to report a profit for the 2nd quarter of 2010, and to plan early IPOs of the government-owned shares.

Yet, the saving of GM was when the litany of Obama “being bad for business” began. GM’s creditors wanted a full bailout on their loans on the basis that “capitalist rules” insist creditors are the first in line under restructuring. Given that millions of investors had suffered as GM stock plummeted during Wagoner’s nine years as CEO, from $70 a share to $3, Obama’s task force stipulated that creditors too would have to “take a haircut” and accept from taxpayers’ money a fraction (29 cents on the dollar) of what they were owed (which was obviously more than the nothing they would have received if GM had been allowed to go under).

The rumblings that the government was taking over too much then rose to a roar over health care reform, which several in Obama’s political team, including Emanuel, counselled postponing, in light of the ongoing economic challenges. A swath of lobbyists armed and financed by the pharmaceutical and insurance companies, as well as the doctors’ associations, had for years made the cause of comprehensive reform to bring the US up to developed-world standards of coverage too costly politically.

But Obama saw health care reform as a basic campaign promise, and also essential for longer-term economic health.

In deciding to go for it, Obama took the opposite approach from the Clinton administration, whose White House task force on health care under First Lady Hillary Clinton presented Congress a vast complete package for approval. This time, the White House urged Congress to come up with a plan that would change the landscape adequately but that would be assured of passage.

The congressional process was ugly, and public debate unpleasantly divisive. From the right, the usual barrage of protest included absurd warnings from the likes of Sarah Palin that the “socialist” health care bill meant Granny’s waning life would be curtailed by “death panels.” After having negotiated for months, Republicans in the House voted against the bill en bloc, and enough Democrats in the House felt the pressure in their districts to make the outcome uncertain.

In the end, in early 2010, Obama won his bet and Congress did adopt a comprehensive health care reform act that would capture about 80 percent of the country’s more than 40 million uninsured through mandatory, if subsidized, health insurance. The administration had to drop the “public option” for everyday care that for progressives was the philosophical core of the health care bill, but the President, as he has shown throughout his life, was willing to sacrifice the perfect in favour of the good and take what he could get.

But the process did not generate warmth in the public’s attitudes toward the US Congress and Washington in general.

Of all topics riling the public, bank bailouts probably topped the list. The issues were always too technical for popular understanding. What people took away was that the banks, whose “greedy” practices were seen to have caused the financial crisis, were being saved with massive injections of public money and yet were continuing to reward themselves with outlandish seven-figure bonuses that the administration (under Wall Street-friendly Geithner and White House economic adviser Larry Summers) consented to because of the perceived “sanctity of contracts.”

Early on, President Obama took “fat cat” bankers to task for being out of touch with the real world with their unjustified bonus payments. Op-ed commentary in the Wall Street Journal, condemned him again as “anti-business,” though in the interests of getting credit and the economy moving, he had rejected more interventionist proposals from the likes of Nobel laureate economists Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz.

In reality, the 2012 political outcome will be determined by what Obama can do now to coax favour from a very vexed public despite unrelenting opponents. Ominous challenges at home and abroad will include “events” we haven’t even thought of.

The administration pulled this one off as well. Almost all banks have been saved and have even paid back their TARP loans ahead of time.

By the summer of 2010, the President was able to get through Congress a financial reform package that would provide future consumer protection from predatory lending as well as re-establishing a 1933 ban on commercial banks’ proprietary trading (i.e., risking depositors’ money on investments for the banks’ own accounts).

These steps will help end bad lending practices and the dishonest bundling of bad loans in secondary investment offerings that led to the collapse of the housing market. Federal housing support agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were in the meantime restructured and recapitalized to save the homes of exposed citizens with a hope of meeting their debts, though the move has meant that 90 percent of new mortgages written in the first quarter of 2010 were government-backed (according to the Economist). All the above — and more — represents one hell of an impressive set of achievements.

Conservative columnist David Brooks wrote in the New York Times that the “bank bailouts and the stress tests …are some of the most successful programs in recent memory. They stabilized the financial system without costing much money.”

Moreover, Brooks went on, Obama “championed some potentially revolutionary education reforms…significantly increased investment in basic research…promoted energy innovation.”

On Obama’s foreign policy to date, it needs to be said that he has pretty much reset US relationships with Russia and China, permitting at least some international traction on the vexing issues of nuclear proliferation, especially by bizarrely self-obsessed regimes in Iran and North Korea.

His own priorities of talking down nuclear weapons and talking up measures to combat climate change received some boosts. Direct presidential diplomacy in negotiation with Chinese, Indian, Brazilian and South African leaders at the Copenhagen climate change summit saved at least a modicum of progress on that essential file.

His impatience with the vanity of meetings taking place for their own sake and for the host’s prestige at home will lead to better international meetings to come. (Exhibit A being the unnecessary and costly Toronto G20 Summit. Philip Stephens in the Financial Times on July 1 accurately depicted Obama’s private assessment of the meeting as “a waste of time.”)

The US military expedition in Iraq was indeed winding down on schedule this summer. The future of that country’s governance is up in the air but at least Obama has delivered on his promise to extract the US from the costly combat role that came with its greatest foreign policy blunder in history.

It is, as always, unclear what will happen in the Middle East, but Obama has changed the tone of mutual expectations with the Muslim and Arab world, and has brokered the re-start of Israeli-Palestinian talks.

A promise unfulfilled is the closing of Guantanamo, largely because the Senate, bending as ever to febrile public opinion, voted in April 2009 (by 90 to 6) to prevent detainees from coming to the US for trial and incarceration.

But Afghanistan is going badly and it is now Obama’s own war. His consultations a year ago on the issue represented the most extensive and intense personal engagement by a president in a foreign policy file in decades, though it is now clearer that upping the ante by another 70,000 US troops may well not be enough to master the Taliban insurgency, which increasingly resembles a civil uprising against a corrupt and unpopular government.

Mastering the rivalries at the top of the US federal machine, especially between the military and civilians, is a daunting challenge for any president coming to government from outside. However, whether by authorizing more Predator hits of identified Taliban and al-Qaeda protagonists than his predecessor by far, or by firing his top Afghan general, Stanley McChrystal, for insubordination, Obama showed he wields the right “command presence” at the top.

So, one is compelled to ask, in the light of what seems a productive job for America in a time of crisis, why is the country so divided about the Obama presidency?

First, America is divided, in many ways. Some are just part of politics in a complex democracy. Obama aimed to get past the divisions, “no blue states and red states, just the United States,” but it hasn’t worked.

Other divisions are deeper, darker and, in the way they impede public focus and grasp of vital longer-term issues, potentially debilitating.

In the foreground, the harsh economic facts stand out, especially jobs.

By the end of 2009, seven million US jobs had been lost in the preceding two years. They haven’t come back; 15 million are seeking work, roughly the number at the bottom of the recession. The administration succeeded in saving many jobs, but again, on the retail political level, saving isn’t credited.

By mid-2009, the economy had eased, but here too, people didn’t generally reward Obama for the improvement. In 2008, housing prices had suffered a 20 percent drop. A 5 percent gain in 2009 was briefly better news but in the summer of 2010, the housing market dipped again.

The breadth of public insecurity is captured by a recent study by the Rockefeller Foundation showing over 20 percent of American households suffered in 2008-09 a greater than 25 percent drop in household income (averaging actually 41 percent). This is devastating stuff politically.

That Obama only inherited this economic mess from the Bush administration and has intervened to try to remedy the damage is true, but it is old news by now, overtaken by popular backlash against the Wall Street bailouts and Congressional wrangling. The US public had pronounced itself on the Bush tenure in the November 2008 election, when even McCain was running against the incumbent’s record. Now, it’s Obama’s performance that is under scrutiny.

The impression of his performance is woven into the public impression of the man himself, framed for many by the drumbeat and innuendo of an intransigent political opposition that panders to right-wing ideologues who believe they are tapping into an anti-Washington public mood, typified by the election in February of Republican Scott Brown in Ted Kennedy’s Massachusetts fiefdom.

Specially motivated is the antitax Tea Party movement, financed by anti-Obama billionaires. Its foot soldiers are overwhelmingly white and older middle-class citizens who are statistically the least likely to support Obama and most likely to buy into the old Reagan line that “government is the problem, not the solution,” even as they cash Social Security cheques and rely on Medicare.

By one poll, a majority of Americans now see Obama as “too liberal.”

He isn’t especially liberal, actually. But right-wing opponents have framed him to seem to many to be part of an Ivy League meritocratic elite, a notion that reminds many Americans that they have been left behind. The framing technique (used in Canada against Michael Ignatieff) takes Obama’s central assets — his intelligence and background in constitutional law, and his “citizen of the world” image — and converts them to negatives showing he is not really “one of us.”

Is race behind the attack politics? Given demographic change and the extent to which younger voters are post-racial, the race factor probably played in the 2008 election as much in Obama’s favour as against him politically. But it is part of the atmosphere, boiling up in controversies such as the quarrel between Harvard professor Chip Gates and local cops, and then a video doctored by a sleazy Tea Party propagandist to portray Agriculture Department official Shirley Serrod as anti-white.

There is a race to the bottom as far as integrity on the facts is concerned. Pew Centre polling this summer shows that 23 percent of Americans believe Obama is a Muslim. Last year, an identical percentage agreed with radio polemicist Glenn Back’s insinuations there is a case for doubt Obama was even born in the US. Loony and spurious claims that a Kenyan birth certificate has turned up can still be consulted in the trash publications at your supermarket checkout counter.

In such an atmosphere of unreality, the Republican Party’s apparent capture by radio demagogues and antigovernment populist circles has made it very risky for its legislators to seek a middle ground with the White House or the Congressional Democratic majority. Several Republican moderates have been ousted in 2010 primaries prior to November’s midterm elections by Tea Party and Palin-supported insurgents.

Obama’s a grown-up and doesn’t complain about the unfairness of some of the calumny. While he sought to be a transformative president, he also sees the country as it is, without illusions.

In the short term, the Democrats will take a hit in November’s midterm elections. Only two presidents since 1862 have made gains in their first midterms after election, and Democrats are now especially vulnerable because they won a lot of marginal seats in 2006 and 2008.

Obama is one of the few American leaders to shoot to the top without prior involvement in his party’s political machine. It is an appealing feature to many in America, where party membership is on the decline and machine politics is anathema. Obama’s personal approval ratings are way ahead of those of either political party or Congress itself.

America is still getting to know Obama. Even supporters who don’t see him taking the country down a road to big-government perdition worry he comes across as too cool, disconnected, too intellectual and even unsentimental, though these are descriptions of him that are mostly inaccurate most of the time.

Obama assumes that treating the political audience as grown-ups is appreciated, and he reciprocates by a sense of proportion in his goals and approach to the issues. His work history has been as a moderate conciliator of competing views, exemplified by the course he gave for a decade at the University of Chicago on US constitutional law. His willingness to see both sides of an argument has led to criticism from progressives he is too willing to “split the difference” on divisive issues. But his is surely the way to go as president of a divided and worried country, where change has been dizzying to many.

In the short term, the Democrats will take a hit in November’s midterm elections.

Only two presidents since 1862 have made gains in their first midterms after election, and Democrats are now especially vulnerable because they won a lot of marginal seats in 2006 and 2008.

How big a hit? At the end of August, Gallup showed Obama’s approval rating had recovered somewhat, about even. But the GOP had an unprecedented 10 point lead on a generic congressional ballot. Fifty-six percent percent of American voters indicate they are more comfortable with Congress and the White House being in different hands.

The Senate is hamstrung already, even with a 59-41 Democratic majority, because of the dysfunctional way the 60-40 closure rule has come to be applied to all debates, not just to vital treaties and other constitutionally mandated special issues.

In the end, the most worrisome thing about American politics is not so-so ratings for a high-expectations president struggling upstream against a swift current of adverse events, especially the economy and Afghanistan. Nor is it that US politics is fractious and divisive.

Nor is it that dumbed-down electronic news media drops substance, balance and due diligence in a race to compete over instant if innocuous headlines. But this does hint at the deeper problem.

The heart of the matter is that the US is on the edge of becoming dysfunctionally incapable of dealing rationally with long-term issues at all.

For some, even Admiral Mike Mullen, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the number one threat to the US is the national debt. For others, it’s the job crisis.

Somehow, the body politic has to accommodate the need for a rational balance between the short-term need of stimulus and the longer-term need of austerity without making either into a partisan call to arms, as is the case for renewing the Bush tax cuts for the top 1 percent of the population.

Though Obama has made his mark by explaining one side of an argument to the other, he has sometimes underperformed in communications, ironic for a leader whom jaundiced older pundits derided for being all speech and no action.

Finally burned by Republican obstructionism and seeing the need to fire his somewhat battered troops up again, Obama has recently begun to take his opponents on with populist language of his own, asking what the outcomes would have been in Detroit, the banks, housing and jobs if Republicans had had their way a year ago.

It is powerful stuff for the converted, and for his political base. But Obama has to mobilize his forte for explaining one side of an argument to the other, and to use the presidential bully pulpit as a “teaching” platform about America’s real choices about the future, setting the argument “we can’t afford it” against the reasons “we can’t afford not to.” In a polarized landscape, he has to take ownership of the centre and reassure independent voters worried about the role of government and the size of the deficit.

Obama has to make the case for government being on the side of America’s “better angels,” able to help the economy mobilize its muscle as well as defending the citizens’ rights. David Brooks recalled the spirit of historic and transformative exercises of public policy in the past, such as the land grants for the US public university system, or the railways and highways that spanned the great nation.

America remains a great human and policy project, one that President Obama is uniquely qualified to define, if the American people can transcend party polemics.

Will enough Americans at least listen? They’d better, for the sake of the country.

Is he up to it? As he said during the campaign, “Don’t bet against me.”

Photo: Everett Collection / Shutterstock