Canadians value their access to an open Internet – that view is on full display at a proceeding currently underway at the federal telecom and broadcasting regulator, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). At the end of January, the CRTC published a formal request by a coalition of telecom and media industry players calling itself FairPlay Canada to set up a private nonprofit corporation to be called the Internet Piracy Review Agency (IPRA). The stated objective and mandate of the IPRA, if adopted, will be to identify and block websites and other Internet resources “that are blatantly, overwhelmingly, or structurally engaged in piracy.”

In the three days after the CRTC asked for public comment, nearly 4,000 individuals submitted their views about the proposal. As of writing, 7,762 Canadians have submitted their views. Why did a proposal aimed at curbing online piracy generate such a strong response? What are Canadians concerned about? We analyzed the first 4,000 public response to this industry proposal to better understand why the general public is so against it.

Canadians for an open Internet

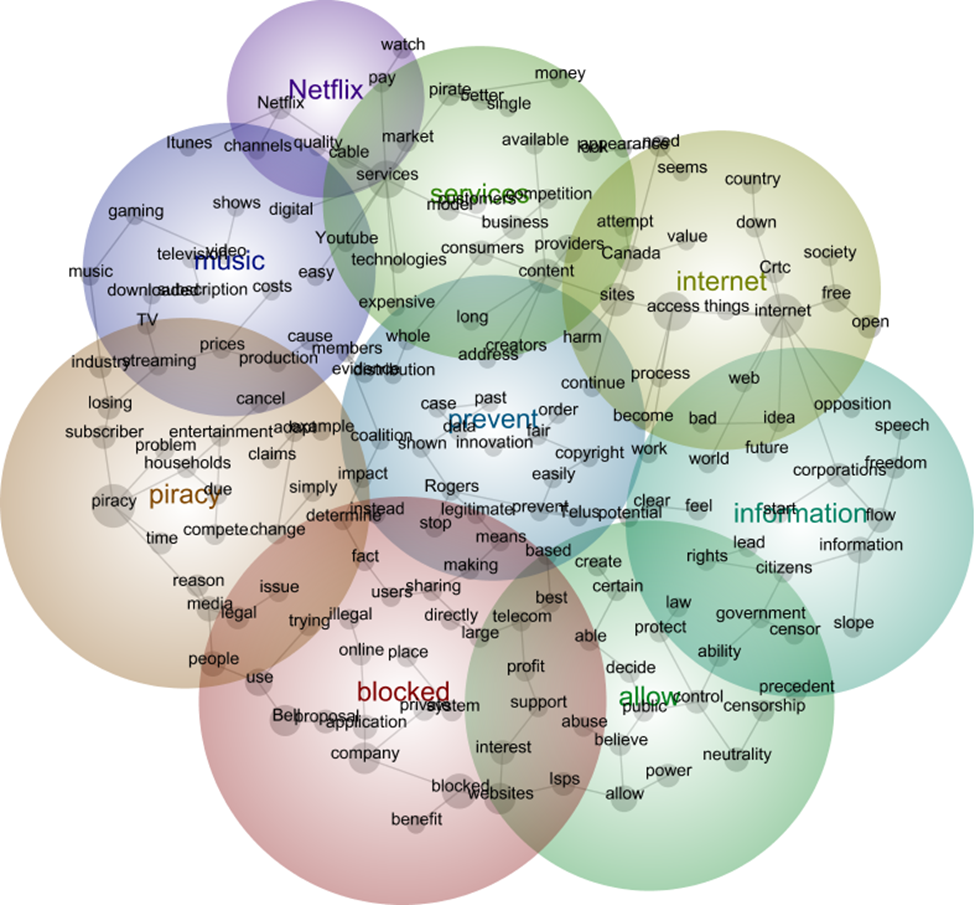

While we don’t want to speculate on the economic and strategic motivations of FairPlay, we think it is critical for policy-makers to appreciate the concerns of Canadians about the proposed extrajudicial blocking regime. Otherwise, we fear that the voice of a narrow coalition of industry interests, in the name of preventing piracy, will suppress legitimate concerns about the unintended consequences of adopting FairPlay’s proposal. To this end, we have analyzed the content of those nearly 4,000 formal submissions to the CRTC. We used quantitative content analysis techniques that allowed us to map statistically significant concepts emphasized by respondents in the text of their submissions, and to examine the relationship among these concepts. We present the results of the analysis with a visual depiction.

Moving from left to right in the diagram, concerns about “piracy” (in the beige bubble) that purportedly motivate FairPlay’s proposal are closely associated with “industry” “losing” “subscribers” due to “streaming.” The key “issue” people have with the proposal appears to be its potential to have a negative impact on access to “legal” “media” “people” want to “use” (at the intersection of the beige and red bubbles).

At the top of the visual depiction, Canadians appear to be reminding policy-makers that they are not pirates and that they already “pay” for digital music and video content from legitimate sources such as “iTunes” and “Netflix.” In the middle of the diagram, a few concepts capture the rational fear of the potential for the proposed regime aimed at protecting “copyright” to actually “prevent” “innovation” by restricting access to “legitimate” material. In the concept clusters on the upper right side, respondents emphasize the “value” they place on their “access” to the “Internet,” and why they believe the proposal represents a threat to their desire to live in a “free” and “open” “society.”

According to their CRTC submissions, Canadians believe that the proposal is a “bad” “idea” because it enables “corporations” and the “government” to restrict “freedom” of “speech” and “flow” of “information” among “citizens.” The fear of setting a bad “precedent” is closely associated with the potential for “censorship” in the future. Overall, it is easy to see that Canadians tend to view the proposed blocking regime not just in terms of its benefits for fighting “piracy”; they also perceive that setting up a national blocking regime may be a threat to their economic interests as “consumers” of “legitimate” “media” and of their political “rights” as “citizens.”

While industry interests in the FairPlay coalition care about financial losses from alleged piracy (by less than 7 percent of households according to data submitted by FairPlay to the CRTC), the general public appears to have a more sophisticated long-term view of the problem that takes into account the risk that the proposed national blocking mechanism may have the unintended consequence of restricting access to lawful material.

Internet governance as a matter of access to information

Media coverage of FairPlay Canada has been quick to frame the issue as one of network neutrality, but our analysis of Canadians’ contributions shows that many oppose the proposed blocking regime because of its potential to end up limiting their access to lawful information from the global Internet.

The future of Internet policy will largely be about limits of control. Various technologies are already being used to restrict unlawful access to copyrighted material, without blocking legal content as can happen with blacklists. Emerging data and algorithmic network control systems promise to stop certain crimes, including piracy, before they happen by identifying pirate-like behaviour. The CRTC decision will impact Canadians’ access to the Internet by influencing choices by the telecommunications industry about which technologies they deploy to limit access to unlawful content.

Judging by their CRTC submissions, Canadians clearly understand the potential of FairPlay’s proposal to restrict their access to legitimate information and to prevent innovation. Lawful material may get caught up in IPRA’s blacklist, and it remains to be seen whether the industry and policy-makers recognize the risk of false-positive errors. Furthermore, it is not evident whether FairPlay’s blocking proposal would actually be effective in curbing piracy because tools to evade IPRA’s blocking regime are easy to access. These include virtual private networks (VPNs) that have legitimate privacy and critical security-enhancing applications, which makes it difficult to restrict their use. As motivated pirates bypass IPRA’s blockade, to achieve its objectives the organization will have strong economic incentives to extend the scope of its blacklist, increasing the likelihood of false positive errors without any compensating benefit in terms of reduced piracy rates.

If policy-makers want to adopt a policy that is in the “public interest,” they should carefully weigh the risks that might result from creating an extrajudicial body that has the authority to control Canadians’ access to the open Internet. Canada’s CleanFeed program already blocks access to websites known to be trading in child pornography. The lack of public concern over CleanFeed suggests that Canadians are willing to accept some regulatory restrictions on the Internet. Should the same type of mechanisms be used to address copyright infringement? What is the threshold to warrant adoption of blocking mechanisms? Canadians seem to have given the CRTC clear answers to these questions.

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The authors would like to thank Jean-François Mezei for collecting the data used in this analysis.

Photo: Shutterstock/ By Pasko Maksim

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.