Cultural appropriation has always been a divisive subject, one on which artists and academics have opined for years. Last week in Canada the topic exploded around the spring 2017 issue of Write Magazine. The Writers’ Union of Canada gave underrepresented Indigenous women, men and Two-Spirit writers an opportunity to have their work published for a broad audience. The editor, Hal Niedzviecki, penned an editorial for the issue titled “Winning the Appropriation Prize,” in which he outlined his belief that cultural appropriation doesn’t exist. He encouraged “anyone, anywhere. . .to imagine other peoples, other cultures, other identities.” This set off a Twitter firestorm, initiated by Haudenosaunee writer Alicia Elliott, whose own contribution to the publication centred on her perspectives on cultural appropriation.

Niedzviecki eventually resigned, which in turn caused an outcry. Several prominent media editors and contributors rose to Niedzviecki’s defence, saying it was a matter of free speech and jokingly offering to chip in for the establishment of the “appropriation prize.” The idea of this prize mocked the rights and concerns of the Indigenous community and highlighted the structures that hold this decades-old debate in its indeterminate state.

What’s lacking in much of the mainstream media’s attempt to engage with this topic is the understanding that, in the Canadian context, the appropriation of Indigenous stories, ways of being, and artworks is simply an extension of colonialism and settlers’ assertion of rights over the property of Indigenous people. The history of colonizing Indigenous identity through images, film and narratives has played its part in placing Indigenous perspectives at a subordinate level. It’s this hegemonic system, filled with stereotypes and suppression, that continues to thrive within institutions. It erects barriers for Indigenous voices.

I’m fond of the old saying, “If you always do what you always did, you’ll always get what you always got,” and this applies across the board when it comes to reconciliation in Canada.

We live in a time where words like “reconciliation” and “decolonization” are tossed about by the media, educational institutions and the bodies that govern these lands. But reconciliation requires changes to systemic barriers and acknowledgement that the lands where we all reside were, and still are, “appropriated” in violent ways. New dialogues that respect Indigenous rights, knowledge and epistemologies must be created. I’m fond of the old saying, “If you always do what you always did, you’ll always get what you always got,” and this applies across the board when it comes to reconciliation in Canada.

For too long, our voices and identities have been controlled and narrated by others, and Western values ranked over our Indigenous ways of being. It was this hierarchy that allowed for the creation of residential schools and the still-extant Indian Act, the purposes of which were to assimilate Indigenous people into the Canadian population. This assimilationist mindset continues to rear its ugly head in conversations around cultural appropriation and the assertion of rights. Today, the word “assimilation” has been replaced with terms such as “multiculturalism” and “freedom of expression.” These seemingly innocent principles give license for Others to continue taking from Indigenous people without consent, encroaching on our rights.

The right to voice our own stories is what we are fighting for. We don’t need others to write or make art about Indigenous realities, we can do that work ourselves.

As distressing as it was to see Indigenous concerns mocked and dismissed, it also emphasized the imbalance of power in the media. These media figures are the gatekeepers who are responsible for ensuring that Canadians are informed on current events and issues. It’s 2017, and I’m continually amazed by how many Canadians have never heard of residential schools or the disproportionate number of missing and murdered women who are Indigenous. The reason behind this lack of information became abundantly clear from the tweets of those people who are charged with keeping Canada informed. In a follow-up discussion on CBC Newsworld of the appropriation prize debacle, former Walrus editor Jonathan Kay assured viewers that diversity was at the forefront of newsroom conversations. But how can there be any meaningful discussion around diversity when diverse perspectives are absent?

Over the past few years, as an Anishinaabe student at two of Canada’s foremost art universities, I’m continually reminded by faculty that the institution is in the process of “decolonizing.” But from semester to semester, I repeatedly have to tame my writing about Indigenous realities so as to not offend my professors. Recently, I had to quietly tolerate a course-mandated talk given by an artist, a friend of my professor, who appropriates Inuit carvings in his sculpture. To those who champion the appropriation prize, self-censorship is seen as the end of their free speech. For Indigenous students, self-censorship is how we protect our grades so we can keep our scholarships.

For true reconciliation to occur, Indigenous perspectives must be heard in any discussion about the institutional barriers that Indigenous people face. The work to bring about change, however slow, has mostly been done by Indigenous writers, artists and academics, who’ve struggled through these systems for decades. It’s time that mainstream media and institutions started to embrace the idea of “reconciliation” as not saying sorry for the past, but as a way to bring Indigenous voices to the table, to listen with respect, and to amend old dialogues in order to create new paths forward.

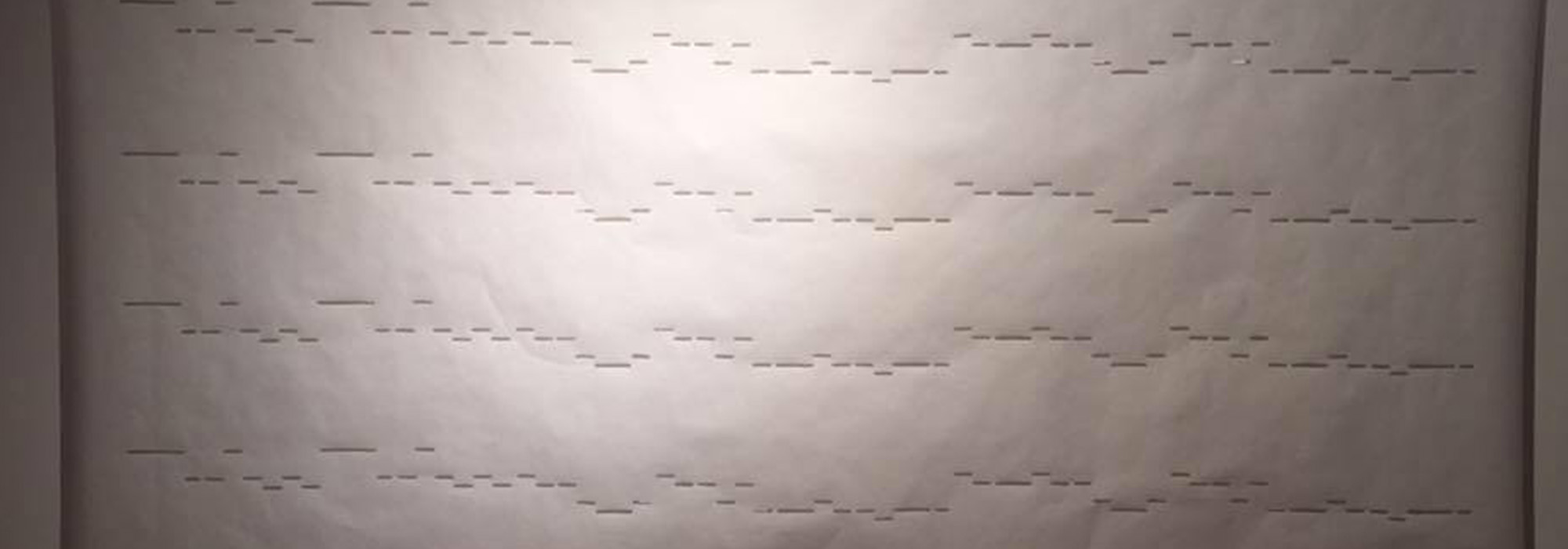

Photo: « Subvert » by Aylan Couchie

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.