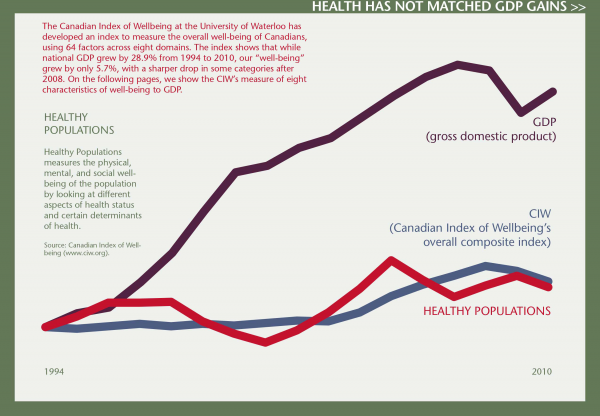

The US and Canadian economies are slowly slipping into a world of mediocre growth, due to an aging population and much slower labour force growth. The Conference Board of Canada expects that the sustainable growth rate for Canada will be dragged down from 3 percent or higher a few years ago to 2 percent annually after 2015 — and it will be even lower than that in central and eastern Canada.

Slower growth will squeeze many elements of Canadian society and will constrain the ability of our governments to finance public goods like health care and education. In a world of mediocre 2 percent growth, higher taxes and/or reduced public services seem inevitable — unless something can be done to create stronger growth.

Recent academic research illustrates that periods of faster economic growth and progressively higher living standards through the ages are the result of technological innovation, invention and mass adoption and distribution of the related benefits. Innovation is the fundamental long-term driver of growth and higher living standards. If Canadians and the governments they select want to encourage stronger economic growth and higher living standards in the future — not to mention high-quality public services, such as health care — fostering greater innovation must be a central focal point of economic policy.

Enhanced labour market policies — for example, an active immigration policy and intense investment in public education and skills development — and tax reform that creates incentives for higher rates of saving and investment can help to push along a growth momentum. However, stronger sustained growth is created through innovation, which raises productivity growth.

So how do we currently stack up? By pretty much every measure, Canada is mediocre at innovation. Canada received a “D” grade in innovation in the Conference Board’s report card “How Canada Performs,” and it received similar low grades in the World Economic Forum’s global competitive index, where we ranked only 14th overall.

Innovation policy and practice remain a quandary. We do not have an “innovation culture” in Canada. And there is no comprehensive “Canadian innovation strategy” that includes governments, business and labour, unlike in countries like Switzerland or Germany that have a collective approach to innovation.

We are ready to act on specific parts of an innovation agenda — such as spending on public education — but we have failed miserably in other priority areas, like investing in modern public infrastructure or converting original ideas and academic research into commercially viable new products and services. Business activity geared toward fostering innovation is not much better, as evidenced by the very low level of business spending in Canada on R&D and on employee skills development.

Moreover, many in North America remain reluctant to engage the full strength of government, in cooperation with the private sector, to launch bold innovation policies and programs that could potentially pay off in stronger productivity and economic growth. John Kennedy’s ambition of getting America to the moon in a decade helped to motivate a nation to innovate, but there is little agreement today on the benefits of significant public investment in big ideas like combating the impacts of climate change, expanding sources of green energy or developing biotechnology.

So Canadians can meekly choose to accept 2 percent growth as the “new normal” — or we can demonstrate that stronger economic growth through innovation is still possible. To make this shift, we would have to develop a robust innovation culture that sets aside fashionable ideologies, encourages creativity and risk-taking, and accepts some modest mistakes along the way. Wider segments of Canadian society will also have to embrace the need for greater innovation. If they don’t, the next generation of Canadians may not have the same opportunities many of us have enjoyed.