What is populism? How does it manifest itself? What are its causes? And is Canada susceptible to the allure of populist politics? These questions are increasingly top of mind for policy-makers and elected officials across the intellectual and political spectrum.

A growing body of scholarship casts new light on the potential nexus between wealth distribution, intergenerational mobility and the makings of political populism. These articles, commentaries and polls ought to be essential reading for parliamentarians this summer.

Cas Mudde is a University of Georgia political scientist whose research and writing on populism has thrust him into the public spotlight in recent years. He presents a nuanced understanding of populism as a “thin-centered ideology” that sees society as divided between elites and regular people. Populism is thus more a stance or a rhetoric, rather than a well-developed world view or a set of policy prescriptions.

It’s also not, according to Mudde, inherently bad. Of course, it can manifest itself in divisive and illiberal ways in certain cases and has done so. But, in a 2015 column in the Guardian, he argues that a positive feature of populism is that it can force elites to address issues that they would prefer to regard as settled questions. As Mudde puts it: “[Populism] criticizes the exclusion of important issues from the political agenda by elites and calls for their repoliticization.” What these issues are and what solutions are put forward ultimately depend on national or local circumstances and what “thicker” ideologies, such as economic collectivism or right-wing nationalism, the populist movement comes to associate itself with.

A New York Times article recently offered an explanation for how Canada has “resisted” the populist wave. Its main thesis is that we have not witnessed political populism because of “strategic decisions, powerful institutional incentives, strong minority coalitions and idiosyncratic circumstances.”

There’s no doubt considerable truth to the author’s findings; for instance, Canada does have a greater economic orientation in its immigration policies. But the case is, in our view, overstated. Bromides about multiculturalism (“a mosaic rather than a melting pot”) are an inadequate explanation. A single visit to Toronto cannot reveal broader economic, political and social attitudes across the country. It seems presumptuous to assume on this basis that Canada is somehow immune to the populist trends seen elsewhere. Canadian policy-makers cannot afford to grow complacent about Canada’s economic, political and social inclusivity.

A June 2017 survey by the Canadian Press/EKOS Politics looked at Canadian attitudes and insights on populism. The results show that “northern populism” may be on the rise in Canada: more than 70 percent of Canadians believe that the conditions for political populism are present. One in five respondents say that a populist movement would be a positive development.

There are limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn from such polling data. The survey seems to assume that “populism” is the same at any time, anywhere, and it neglects the extent to which the circumstances are different in various countries. There’s a tendency to overstate commonalities when one searches for a general theory or a simple narrative.

Populism tends to take on national or local characteristics. Its manifestation in Canada would probably assume Canadian features such as an urban/rural divide (as we recently described) or regionalism, as it did in the late 1980s with the Reform Party. Former Toronto Mayor Rob Ford’s political resonance is another good example of how populism is shaped by local circumstances. Ford appealed to underrepresented constituents in Toronto’s often forgotten inner suburbs to rally voters against the city’s downtown elites. In adapting to a city with as many newcomers as Toronto, Ford’s populism didn’t come with the type of anti-immigration baggage that right-wing populism is often associated with elsewhere.

One factor that could contribute to the rise of populism in Canada is the growing perception of a lack of broad-based economic and social opportunity across the country.

Still, recent polling data are illuminating in that they show the potential fecundity of the populist message in general. One factor that could contribute to the rise of populism in Canada is the growing perception of a lack of broad-based economic and social opportunity across the country.

A new essay by the Harvard economist Edward Glaeser on the “war on work” cites working-class joblessness as the source of the current political and social unrest south of the border. He points to falling employment rates for prime-age men (ages 25 to 54) as contributing to a spike in social pathologies, ranging from family breakdown to opioid abuse.

What’s unique about his analysis is that Glaeser doesn’t attribute the decline in employment rates solely to market forces such as trade-induced dislocation or technological innovation. Government policies such as rising minimum wages, overly generous disability benefits and income supports that impose high marginal effective tax rates are also contributing to the problem. It’s a good reminder that the first priority for policy-makers must be a politician’s variation of the Hippocratic Oath: first, do no harm.

What is Canada’s experience of underlying trends of declining economic opportunity, like those observed in the US? It’s an important question, especially since there’s considerable evidence that these socio-economic issues have contributed to the rise of American populism.

A Globe and Mail commentary draws heavily on the research of the leading Canadian economist Miles Corak to highlight the relationship between where a person lives and the prospect for social mobility. The analysis finds that intergenerational mobility — that is, the likelihood that people will have higher income than their parents did — may be more associated with where people grow up than with other factors such as family circumstances or culture.

The largest urban metropolitan areas, such as Vancouver, Calgary and Toronto, are “mobility springboards” where adults’ incomes often exceed those of their parents. Central Alberta, southern Saskatchewan and southwestern Ontario are similar springboards. Parts of Manitoba and coastal British Columbia, by contrast, are identified as “mobility traps” where people rarely move up the income ladder.

This geographical analysis has immediate-term implications for policy-makers and elected officials, suggesting reforms ranging from redesigning income-support programs to incentivize labour mobility to adjusting zoning policies to enable housing affordability in high-demand markets. We must make it easier for people to respond to labour market signals in our most dynamic and job-creating cities and regions.

But there’s also a long-term need to expand economic and social opportunity in rural and less prosperous communities. Not everyone can simply relocate to major urban centres, and not everyone would choose to. Experimenting with economic development policies such as tax-preferenced enterprise zones may be part of the policy response. Removing regulatory and policy obstacles to resource development, which is a major source of employment for rural Canadians, is surely another. As Glaeser points out, not all employment dislocation is caused by market forces; policy-makers share the blame and can contribute to solutions.

The Université Laval economist Stephen Gordon’s recent analysis of Canada’s changing labour force provides additional insights into economic and social opportunity in the country. His work shows a major shift in the share of the employed population with post-secondary education. Twenty percent of full-time workers had a university degree in 1997; now one in three do. As many as one in six did not have a high school diploma in 1997; that’s now the case for only one full-time worker out of fourteen.

Gordon rightly observes that this 20-year shift cannot be fully explained by rising educational attainment rates. It also reflects low-skilled Canadians dropping out of the labour market. Still, this change in the educational composition of Canada’s labour force is a major development with considerable policy and political implications.

Policy-makers must continue to make post-secondary education accessible for Canadians, irrespective of income and background, and it must become more flexible and responsive to student needs and evolving labour market demands. This doesn’t mean that bureaucratic planners ought to be perpetually adjusting curriculum based on perceptions of economic trends. But we should continue to move in the direction of mixed degree offerings (such as economics and biology, or Spanish and engineering), more co-op programming and an emphasis on basic skills and knowledge such as writing, critical thinking and foundational ideas.

The declining yet significant numbers of Canadians without post-secondary education cannot be forgotten, either. These are the workers who are disproportionately vulnerable to trade- or technology-induced dislocation. There have been some signs of a greater policy focus on non-university-educated Canadians, such as the renewed emphasis on polytechnic education by the Harper government; a political consensus in favour of expanding the Working Income Tax Benefit; and more responsive retraining programs such as the Canada Job Grant. But more attention and focus is needed to improve economic opportunity for those without university education.

It’s positive that journalists and scholars are thinking about the rise of populism, the responsiveness of our democracy and how to enable greater economic and social opportunity across Canada. Our policy-makers and elected officials must think about these issues, too, and should keep on reading between now and Parliament’s return for the fall session.

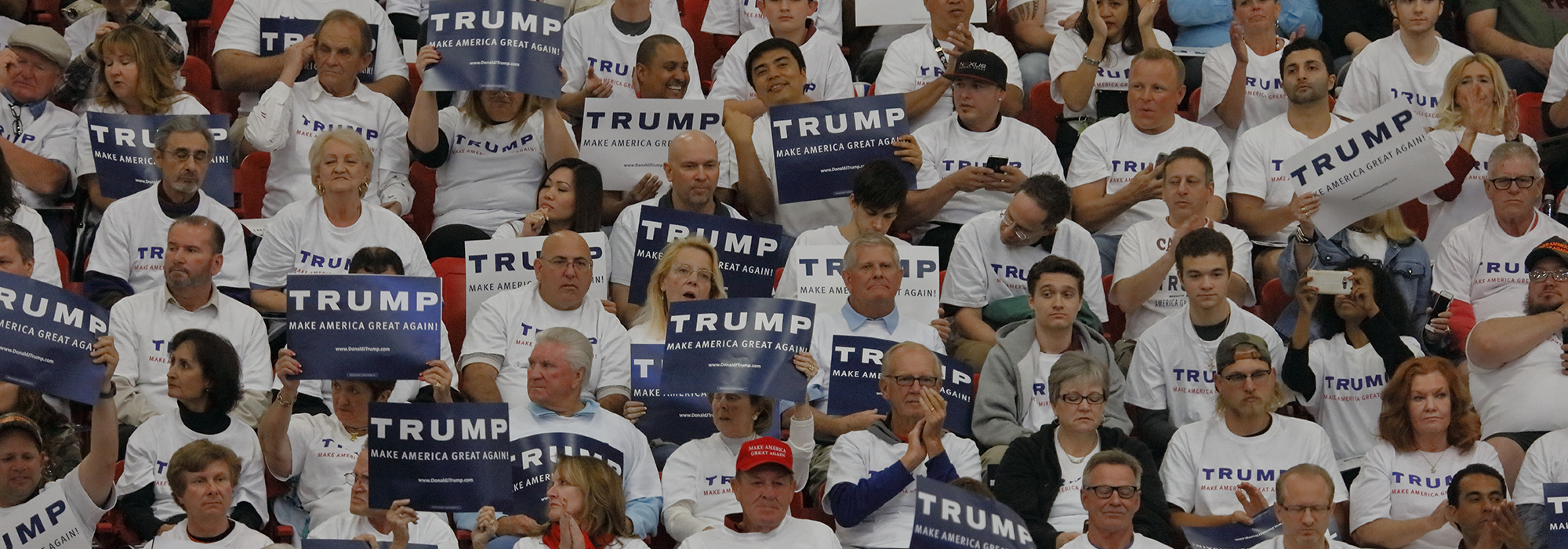

Photo: Shutterstock/Joseph Sohm

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.