In popular media and policy debates, people in rural Canada are often labelled “backward” in their political views and accused of intolerance within the otherwise vibrant cultural mosaic of Canada. Stephen Harper, while in opposition, even attributed Atlantic Canada’s economic underdevelopment to a “culture of defeatism,” and as prime minister he brought in changes to employment insurance that largely affected rural areas. With the election of Donald Trump in the US and the rise of right-wing parties in Europe, the focus on rural attitudes and the “urban-rural divide” has intensified. Working-class voters from rural regions are blamed for supporting and electing conservative and populist governments. These stereotypes might be valid in the US and in other contexts, but whether they apply to Atlantic Canada is less clear.

Despite its reputation as conservative and averse to change, polling data from a number of national firms consistently find that Atlantic Canada is more progressive and open to immigration than other parts of Canada. The region’s long-standing Red Tory tradition also suggests it is more comfortable with state intervention and progressive economic policies than other parts of the country. These findings are shown through research published in two reports on political views and practices in Atlantic Canada by the Perceptions of Change project, with support from the Rural Futures Research Centre and in conjunction with the MacEachen Institute for Public Policy and Governance. The reports, based on a survey conducted in early 2019, find that rural Atlantic Canada appears to be highly politically engaged but not particularly conservative.

Rural Atlantic Canadians said they voted more frequently than those living in urban areas, and they protested at a similar rate as city dwellers. Rural residents were also more likely to say that their participation in politics had increased over the last few years, with 19 percent reporting that their participation had gone up, compared with 14 percent of urbanites. Overall, rural residents seem to be more politically engaged.

When it comes to political views, findings were mixed, and differences were not clear-cut. On social issues such as immigration and openness to diversity, rural residents were more conservative than their urban counterparts, but not by much. For example, 73 percent of rural residents surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that immigrants bring vital skills and resources that benefit the Canadian economy, compared with 77 percent of urban residents. These numbers don’t point to stark differences between city and country or a great deal of intolerance toward outsiders in either urban or rural areas, busting that myth about rural Atlantic Canada.

On economic issues, urban Atlantic Canadians tended to be slightly more conservative than rural residents. For instance, 68 percent of city dwellers agreed or strongly agreed that the minimum wage should be raised substantially, compared with 72 percent of rural participants; 84 percent of urban participants were in agreement that it is the government’s responsibility to ensure that everyone in Canada has access to essentials, while 86 percent of rural participants said the same. Again, the myth of the conservative rural resident doesn’t hold much weight.

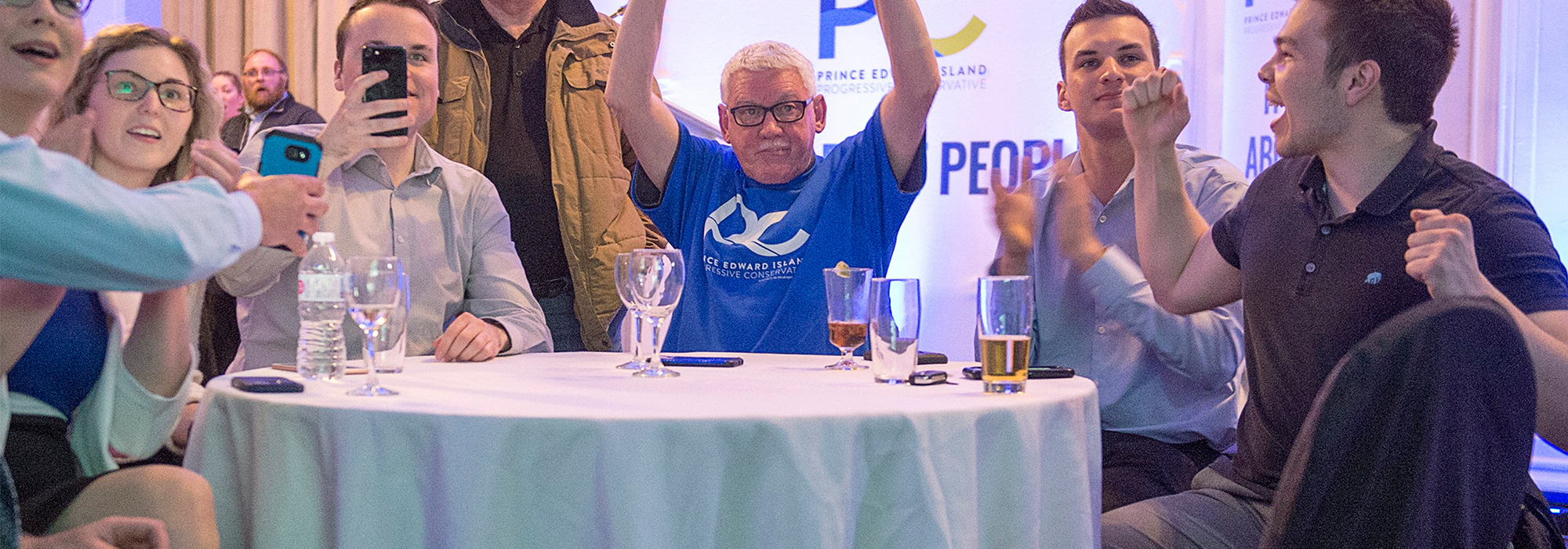

Additionally, a higher percentage of rural Atlantic Canadians said their political views had changed “a lot” in the last few years: 17 percent, compared with 11 percent of those in cities. In total, 65 percent of both urban and rural residents said their views had changed either “somewhat” or “a lot.” Voters in the region aren’t shying away from electing new candidates, either. The 2018 election in New Brunswick saw Green Party candidates elected for the first time, as well as candidates from the new People’s Alliance party. In the April Prince Edward Island election, Greens won almost a third of the seats, showing a willingness to break with the two-party tradition. In both provinces, incumbent premiers were defeated. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the May 16 election brought in the province’s first minority government since the 1970s and elected independents for the first time. Clearly Atlantic Canadians are not stuck in their ways — another myth busted.

Across urban and rural Atlantic Canada, there is a great deal of common ground on social and economic issues to provide the basis for political action, and there is little evidence for the “urban-rural divide” as a major political force in Atlantic Canada. It may be time for stereotypes of Atlantic Canadians as conservative and averse to change to be put to rest.

Photo: Progressive Conservative supporters cheer as they watch the returns in the Prince Edward Island provincial election in Charlottetown on Tuesday, April 23, 2019. The results: the Progressive Conservatives will form a minority government with the Green Party as the opposition. The Canadian Press, by Andrew Vaughan.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.