We launched the Canada Beyond 150 initiative in June 2017 (see our earlier Policy Options article) as an experiment to test some bold assumptions about policy-making. If Canada’s 150th anniversary kicked off conversations about the future of the country, our project within the federal public service would be a test kitchen for the future of policy development and the skills and techniques to support it.

Would a consciously diverse and inclusive approach to policy development bring in new voices, tools and methods, and ultimately lead to better outcomes? Could a curriculum that blended foresight analysis, meaningful engagement and design thinking yield new, interesting insights and relevant policy proposals? What would happen when we challenged a new generation of public servants to embody a more open, inclusive and innovative federal public service?

We are now halfway through that project. As champions for an experiment like this, we want to share some of what we’ve learned to date.

One of our challenges has been to live up to our core principles on diversity and inclusion. The recruitment process for Canada Beyond 150 got off to a strong start in this respect. We recruited over 80 early-career public servants from an array of backgrounds, and we are proud to say that our cohort well exceeds the public service’s figures for representation of women, visible minorities, Indigenous people and people with disabilities.

But exceeding representation levels for the public service is not the same as meeting the representation expectations of the public. Working through our project themes (reconciliation, feminist government, socio-economic inclusion, sustainable development and open and transparent government) has reinforced the extent to which visible representation and inclusion need to be built into our policy development processes. If we are organizing a panel that speaks to issues on reconciliation, then Indigenous people need to sit on the panel. If we are organizing a session on feminist government, then participants should reflect the spectrum of gender identities. More than before, we are realizing the need for demographic groups implicated in a policy area to be visibly involved in the analysis and the work.

How can you have a strategic conversation about the future of reconciliation or feminist government when so many of the challenges in these domains are rooted in the past?

We are also facing difficulties in how we use foresight, which looks at how technological, environmental, social and economic changes can potentially create policy challenges and opportunities well into the future. On the one hand, we are teaching our participants the skills and methods to support a strategic conversation about the future of a policy area. On the other, we are learning that it is sometimes hard to see issues through the lens of the future. How can you have a strategic conversation about the future of reconciliation or feminist government when so many of the challenges in these domains are rooted in the past — in long-standing, pressing issues related to quality of life and equity?

Similarly, on open and transparent government, how can we look beyond the planning efforts and foundational work under way on this issue, to have a strategic conversation about open government 10 years in the future?

For our project, one of the best answers to these questions is to engage more deeply. Collaborating and discussing the issues with our partners and stakeholders, who live in their reality every day — citizens, professionals and members of civil society organizations, academics and experts — is proving to be an effective model.

Our interactions with our partners have forced us to rethink our assumptions and sharpen our questions and areas of focus.

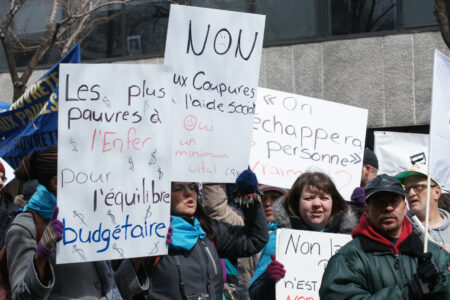

This dialogue can bring us, as policy-makers, to some hard places. One of our teams exploring socio-economic inclusion is focused on the issue of capital and debt. Many of the team’s partners work on a daily basis with clients living through the cycle of debt accumulation. While our participants are focused on the future of capital and debt, including the emergence of virtual currencies and other innovations, a common message from their partners has been that those people struggling under debt in the established system cannot be forgotten or allowed to fall further behind. Our participants’ assumptions did not fit the reality on the ground, and they had to recalibrate. Indeed, the paradigm for Canada Beyond 150 is that our interactions with our partners have forced us to rethink our assumptions and sharpen our questions and areas of focus.

Overall, however, the challenges we have faced aren’t surprising; they are at the heart of the experiment.

There is a serendipity to them, too. This came into focus more than ever during our mid-project working meeting in Winnipeg in November. At that meeting we created an immersive activity that showcased emerging issues in each of our thematic areas. The activity allowed Canada Beyond 150 participants to share their findings thus far with stakeholders. The one-on-one meetings brought forward difficult questions, to be sure. But it has been through those encounters that we have been able to build deeper relationships and sustain a productive two-way dialogue.

We launched Canada Beyond 150 as an experiment in Canadian policy-making. What we’ve learned can be lessons for others; our approach can blaze a trail for others in government to follow. By definition, the learnings and outcomes from Canada Beyond 150 cannot be the final word. They are part of a conversation, and we invite the broader policy community to engage with the work, take up the approaches and build on our learnings.

Photo: Shutterstock/By GN ILLUSTRATOR

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.