The image of a religious leader placing in the ground an Indigenous child whose life was snuffed out due to a nation’s hatred for its First Peoples is not an image I care to entertain. However, with more and more unmarked graves continually being discovered across Canada, the thought has become ever more present.

The numbers – media reports say more than 1,000 while the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s estimate is closer to 3,200 – serve as a solemn reminder that behind every child’s body found, there was an individual putting them there, supported by a system that perpetuated the logic that it was okay. How did we get here, and in what ways has spirituality been used to justify burying Indigenous children this way? Can spirituality also be an opportunity for critical dialogue and healing?

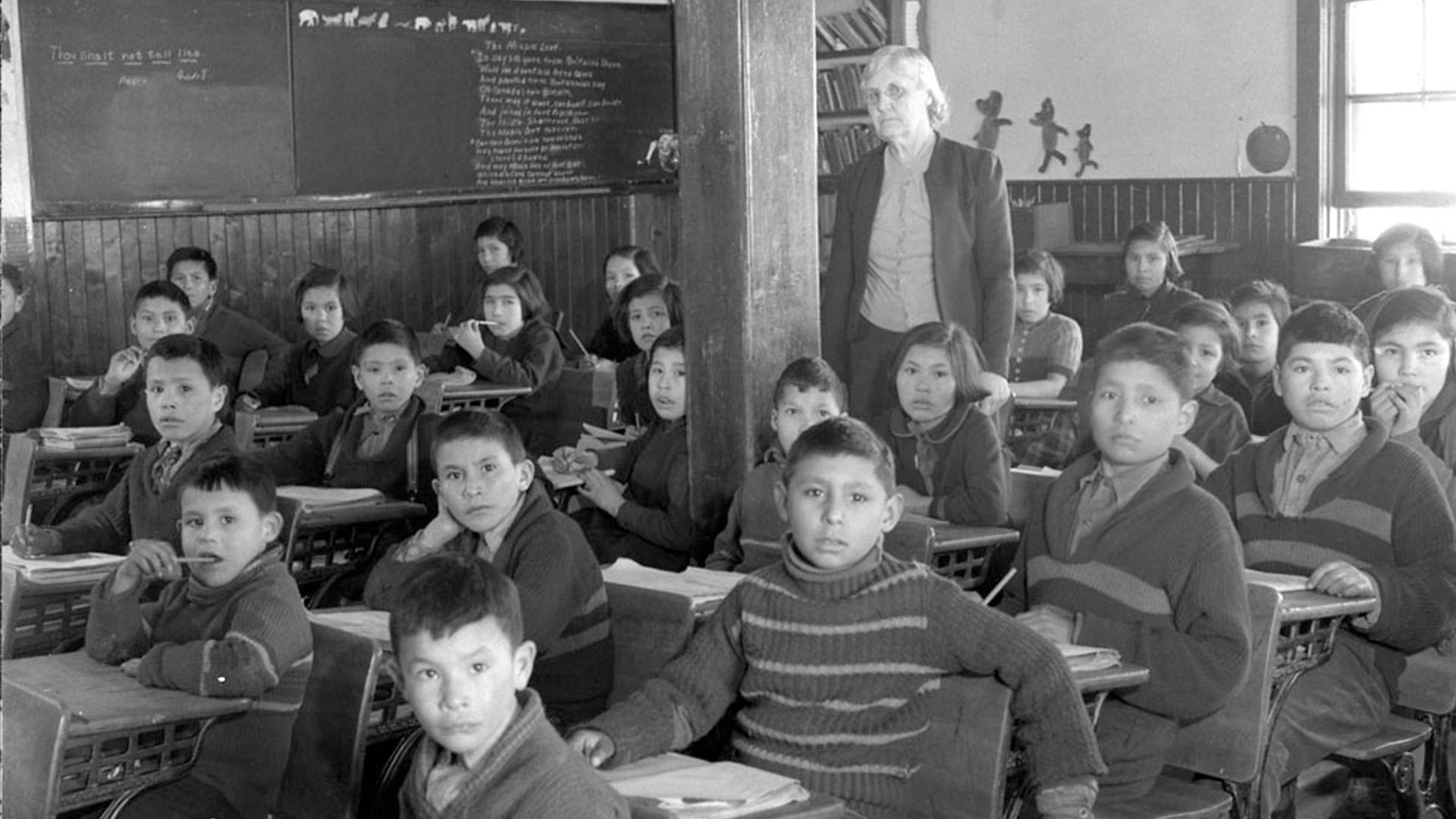

Pope Francis is set to arrive in Canada on July 24. He comes at a crucial time when Canadians need to critically question the ways that spirituality has negatively impacted our social and political practices. Reconciliation needs to take into consideration Canada’s past and ongoing history of spiritual abuse, as I have argued. Most of the schools in the Indian residential school system were run by the Catholic Church. At their core were issues pertaining to power, spirituality and violence. A conversation about reconciliation is a question about spirituality and how Canadians of all backgrounds can spiritually heal from Canada’s past and ongoing history of settler-colonialism.

Fear and discomfort shouldn’t block anti-racism efforts in schools

Reconciliation needs to address Canada’s history of spiritual abuse

What’s standing in the way of teaching about residential schools?

The spiritual codes of conduct that regulated the relationship between settlers and Indigenous Peoples arguably began with the early days of European contact. Colonization was a religious endeavour meant to alter the spiritual fabric of Indigenous societies. According to scholars such as Susanne Lachenicht, “colonization was also about converting the ‘heathen’ to, first, Catholicism, and then, with the Reformation and the rise of different varieties of Protestantism, to other denominations as well. Colonization in the early modern period was as much about religious missions, about ‘the harvest of souls,’ as it was about expanding territorial boundaries and economic resources.”

The 2012 Truth and Reconciliation Report highlights the tensions at play between Christian religious institutions and Indigenous Peoples, noting that “to both Protestant and Catholic missionaries, Aboriginal spiritual beliefs were little more than superstition and witchcraft. In British Columbia, William Duncan of the Church Missionary Society reported: ‘I cannot describe the conditions of this people better than by saying that it is just what might be expected in savage heathen life.’ Missionaries led the campaign to outlaw Aboriginal sacred ceremonies such as the Potlatch on the West Coast and the Sun Dance on the Prairies.”

Early “discoveries” of North America positioned Indigenous people as savages in need of Christian saviours to guide their souls along a path to religiousness. Violence was used as the path to that end. The residential school system was a product of this mentality. Underpinning these ideas is the belief that violence is supported by God and that child welfare comes from the suppression and punishment of identities deemed to be outside the white, heteropatriarchal norms set by Christian religious institutions.

As a nation, Canada needs to hold to account those responsible for perpetuating these abuses. With residential school sites now being treated like crime scenes, we often ignore the fact that while the residential school system created many victims, it also created opportunities for acts of violence to remain hidden in society.

Spirituality led us to this place, but it can also be an opportunity for healing and reflection.

Beyond punitive measures, which some Indigenous communities might themselves question, those responsible need to come face-to-face with the realities and impacts of their actions. Conversations should be centred on Indigenous spiritual principles. For example, Indigenous understandings of restorative justice focus on the “connection the people have with spirituality and the emphasis on making reparations, restoring relationships and healing from wrongful behavior.”

Indigenous healing lodges across Canada position spirituality as a way of understanding the motivations of Indigenous and non-Indigenous offenders. They also use spirituality to identify paths forward for the offender.

The state and institutions that played a part in putting the children in the unmarked graves must also be held responsible. Accountability can come through education with the hope that by teaching people about the atrocities of the past, they will never happen again. Even now, as a graduate student, I find myself shocked by how many educated, well-intentioned people I encounter who either do not know about the residential school system or do not understand the depth of the impact this act of genocide has had on Indigenous communities.

Meanwhile, there have been attempts to limit discussion about the residential school system, an example being Alberta social studies curriculum adviser Chris Champion referring to the inclusion of Indigenous content as a fad. Former senator Lynn Beyak has unapologetically argued that the positive elements of residential schools go unacknowledged, which in her view include converting Indigenous Peoples to Christianity. These remarks are problematic as they show a lack of critical awareness about Canada’s relationship with its violent past. With the overturning of Roe v Wade south of the border, we have seen how quickly a country can move backward under the guise of spiritual affirmation.

As a nation, Canada needs to be aware of the ways that spirituality is used to justify awful abuses of power.

Finally, we need to come to a better understanding of the ways that spiritual abuse still permeates the very fabric of North American society. An appeal to religion to justify abuse has been seen in debates about issues such as conversion therapy, the presence of drag queens in libraries in both the United States and Canada and the overturning of Roe v Wade in the United States. These incidences highlight the ways that an appeal to spirituality becomes the mechanism for the removal of group identities, the limitation of rights, and the justification of the violence enacted.

These systems of power appeal to spirituality to target those at the margins of society. Spiritual abuse, therefore, creates a fractured society insofar as it normalizes and justifies some acts of violence while pushing Indigenous peoples and others to the margins. More than ever, we need to consider which groups have become the targets of spiritual abuse, and what voices and what lives are snuffed out when we use spirituality as a justification for violence.