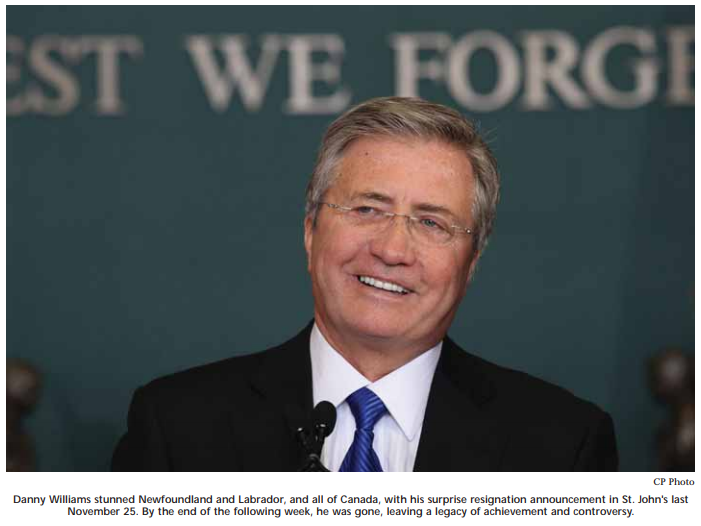

On November 25, 2010, Danny Williams stunned Canada. He announced his resignation as premier of Newfoundland and Labrador, as leader of the Progressive Conservative Party and as a member of the House of Assembly. All this, with just a week’s notice. On December 3, Williams became a private citizen. He had been in provincial politics 10 years, the last seven as the ninth premier of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Williams’ rapid departure was stunning for many reasons. Earlier, he had made it known that he intended to seek a third term. Also, it had been only a week before his resignation notice that, with much fanfare, he officiated over the announcement of a major project. He had a preliminary agreement, a “term sheet,” under which the province’s energy corporation, Nalcor, would partner with Emera Inc. of Nova Scotia to develop the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric site on the lower part of the province’s Churchill River. A portion of the new energy would meet provincial demand and the surplus (since the province is not big enough to take all the new supply) would be transmitted via subsea cables to Nova Scotia for sale. Developing the Lower Churchill had always been a top, even cherished priority for Williams, but as with other premiers before him, it had proven especially difficult to get going. The term sheet is a significant achievement but it is really an embryonic agreement. Many technological, environmental and financial issues still must be addressed, and the key interested parties, including the Innu, all have to be satisfied. In addition, the larger undeveloped hydro site on the Lower Churchill, at Gull Island, has been left in abeyance for now. It is surprising that Williams, a man known for his eagerness to face challenges head on, decided to remove himself from involvement in this file at such an early stage.

And it truly was his decision to leave. Neither scandal nor popular discontent was at play. Williams’ popularity was the envy of any politician. Who else could boast of an approval rating in excess of 80 percent? His party held 43 of the 48 seats in the legislature and, under his leadership, was likely to do as well in the next election. He was totally in command of his party caucus and cabinet; no Gordon Campbell or Shawn Graham problems here! With the next provincial election only 10 months away, practically all of his party’s candidates could expect easy wins on his coattails. Few would have had to do much heavy lifting. Now, his departure changes that; the opposition parties’ prospects have improved considerably.

What politician would pull out of politics in such an unassailable position? Williams has offered the explanation that he felt it was “time to go.” That’s hardly enough of an elaboration. Some may speculate about his health, especially in light of the heart surgery he had early in 2010; a somewhat controversial topic since he opted to have the surgery in the United States. However, just after his announcement, Williams addressed that possible explanation directly, asserting that his health is excellent. So it might well be some time before we know more about the motives for his decision to go.

Williams’ resignation was a bold, self-made decision that surprised, even astonished many. That characterization is consistent with his modus operandi as a political leader and premier. It is worthwhile to look back to see where that approach did and did not pay off for him.

In 2003, when Williams was first elected as premier, his victory was substantial but not overwhelming: 34 out of 48 seats. He was also handicapped by the poor financial circumstances of the province at the time. Early in his regime and based on external assessment of those finances, he made a television broadcast to let the people know that severe austerity measures were coming. Those measures included public sector wage restraint. The austerity program was not popular, and the wage restraint resulted in a public sector strike. In an effort to settle the strike, Williams made some bold and surprising moves. On one occasion, he jumped over the negotiation process and met directly with a union leader, apparently at a secret location in a car. On another occasion during the strike, Williams waded directly into a group of picketers in an effort to convince them to accept the government’s terms. Despite these bold one-man moves, an agreement was not possible, and Williams had to resort to legislating the workers back to their jobs and imposing the government’s terms on them. Needless to say, the trade union movement was unhappy with this outcome, and the public was not especially pleased by the general austerity measures that the newly elected government had imposed. Still, Williams had established himself as a determined political leader.

It truly was his decision to leave. Neither scandal nor popular discontent was at play. Williams’ popularity was the envy of any politician. Who else could boast of an approval rating in excess of 80 percent? His party held 43 of the 48 seats in the legislature and, under his leadership, was likely to do as well in the next election. He was totally in command of his party caucus and cabinet.

Also, during his early years in office, Williams made quick and bold personnel decisions that were not especially popular. He moved a well-respected cabinet minister back to caucus for disagreeing with his decisions affecting that minister’s portfolio, and a parliamentary secretary was eventually thrown out of caucus for publicly disagreeing with provincial fisheries policy. At the senior levels of the public service, Williams also let a few people go and asserted his authority strongly. These controversial decisions were not generally perceived in a way that added to Williams’ popularity. However, his boldness and steadfastness in facing external challenges would.

In 2003, Williams’ Progressive Conservative election platform had emphasized the importance of realizing more benefits to the province from its natural resources. By this time, offshore oil production was in its seventh year but net revenues to the province were modest. A provincial royal commission report published in 2003 and commissioned by the previous provincial Liberal government demonstrated that under various scenarios, most of the government revenues from offshore oil developments would actually accrue to the federal coffers. The federal government gained primarily by its corporate income tax take and its savings in Equalization payments to the province. In the case of the latter, as provincial revenues from offshore oil increased, Equalization payments from Ottawa to the province would fall by a sizable proportion. This so-called “claw back” effect, which reflects the way the Equalization formula is designed, meant that the net gains in provincial revenues from offshore oil would likely be modest. To a degree, the 1985 Atlantic Accord, an agreement between the provincial and federal governments on offshore oil management, addressed this clawback effect. That accord provided for special payments to the province that would partially offset any annual declines in Equalization payments. However, these offsetting payments were only a temporary provision within the Accord; the last year in which there could be a payment would be 2010/11. By 2003 it appeared that offshore revenues would peak after that time, with the fiscal gains to the federal government turning out to be much greater than the net gains to the provincial government.

Williams used the June 2004 federal election to pressure federal party leaders to support improvements to the Atlantic Accord. While campaigning in St. John’s, the Liberal leader and prime minister, Paul Martin, met with Williams and publicly announced that he had accepted Williams’ proposal on offshore revenues as discussed in their meeting. It was quite surprising that Martin defined his pledge in terms of what Williams was looking for rather than stating what he was prepared to do. He allowed Williams to define the package. And Williams made it clear that his proposal was for Equalization payments to be calculated without taking into account the province’s offshore revenues for the life of the oil fields.

Martin’s Liberals were reelected with a minority. Williams lost no time in writing to Martin to remind him of his election pledge and laying out the core elements of his proposal on offshore revenues. Responses from the federal government did not immediately follow. This was probably due to second thoughts as the federal bureaucracy, and some provinces, Ontario in particular, were not supportive of what Martin had apparently agreed to. By the fall of 2004, the feds were putting conditions on any additional payments, such as a cap on annual payments and a limited time frame. Frustrated with the lack of progress, Williams made a number of media-attracting moves that put his dispute with Martin in the national limelight. In October he walked out of a federal-provincial conference in protest and repeatedly reminded Canadians that Martin was failing to live up to his word. In December, Williams accepted an invitation to meet with the federal minister of finance, Ralph Goodale, to resolve the impasse. Williams left that meeting in apparent frustration and anger — the federal position was unacceptable. Shortly thereafter, just two days before Christmas Day, Williams made his most brazen move yet, an action that got Canada’s attention. To protest Paul Martin’s failure to keep his word to him, Williams ordered that all Canadian flags on provincial buildings be taken down. Within the province, most people rallied around Williams’ dramatic gesture, but nationally the reaction was extensive and highly critical. Yet by January the flags were flying once again, and the Premier was back in Ottawa making a deal with the Prime Minister.

On January 28, 2005, a deal was at hand. Williams returned to Newfoundland and Labrador with a hero’s welcome at the St. John’s airport. Martin had given more ground. Williams, too, had compromised; he did not have a guarantee of more offset payments over the life of offshore production. However, he got a guarantee of increased offset payments to 2011/12 and the possibility of more, depending on the province’s fiscal conditions; and, as an assured minimum benefit, a $2-billion advance payment. Williams’ boldness in confronting the Prime Minister, his tactics to keep the issue in the national spotlight and his steadfastness in the face of harsh media criticism had paid off. The province would get more fiscal benefits from offshore oil. His popularity at home soared. In 2007 he won a second mandate with an overwhelming majority: 44 out of 48 seats and 70 percent of the popular vote. In contrast, Martin lost the 2006 federal election to the Conservatives under Stephen Harper.

Williams was not so unambiguously successful in his Anything but Conservative (ABC) intervention in the October 2008 federal election campaign. The catalyst for the ABC tactic was the decision by the federal government to make changes to the Equalization formula that would have the effect of mitigating some of the gains that Williams had won from Martin. In particular, the federal government adopted a formula that would reduce its Equalization payment to a province if that province’s fiscal position, inclusive of Equalization, would have otherwise been brought above that of a nonrecipient province. When it came to Newfoundland and Labrador (and Nova Scotia, which also had similar offshore fiscal arrangements), its fiscal position would be measured by including its Equalization entitlement plus the offset payments from the federal government. This created an awkward contradiction. The purpose of offset payments was to compensate for reductions in Equalization, but now reductions in Equalization were to be calculated according to the size of the offset payment. Nevertheless, the federal bureaucracy found the legislative language to finagle its way out of that circular logic.

The results of the ABC tactic were mixed. The Conservatives won the federal election and increased their seats, although they remained in a minority situation. Beyond Williams’ home turf, few Canadians were swayed by his appeals. Harper had not given in to pressure and made concessions as Martin had. And there was no longer any MP from Newfoundland and Labrador in the federal cabinet.

Williams angrily denounced the changes to the Equalization formula. He pointed out that this undermined the 2005 agreement, and he reminded Canadians that the Conservative leader, Stephen Harper, had gone back on his pledge to remove nonrenewable natural resource revenues from the Equalization formula. His attacks on the Conservative federal government and Prime Minister Harper were harsh and pointed. And when the federal election was called, he launched his ABC campaign in earnest, a campaign not limited to his home province. It was a national effort to discredit the federal Conservatives.

The results of the ABC tactic were mixed. The Conservatives won the federal election and increased their seats, although they remained in a minority situation. Beyond Williams’ home turf, few Canadians were swayed by his appeals. Harper had not given in to pressure and made concessions as Martin had. And there was no longer any MP from Newfoundland and Labrador in the federal cabinet.

However, at home, the story was different. Conservatives lost the three seats that they had held and their popular vote fell to a very poor third place. It was now clear that any MP from Newfoundland and Labrador, regardless of party affiliation, could be brought down by Danny Williams. On top of that, Williams had reinforced the perception that anyone who threatened his province’s interests would be relentlessly challenged by him.

Surely, one odd forum in which to defend those interests was the Larry King Live show. In 2006, there was Danny Williams debating with Sir Paul McCartney and Heather Mills McCartney. The topic was the seal hunt. Williams stood his ground in defending the seal hunt against the world-famous and highly popular Sir Paul.

Also, Williams became well known for his biting criticism of Quebec. A great deal of his animosity toward his neighbour stemmed from frustration over the development of the hydroelectric potential on the Lower Churchill River. Making a deal with Hydro-Québec to wheel through Quebec has proven to be very difficult, and disputes are ongoing. The hugely disproportionate benefits accruing to Quebec from the 1969 Churchill Falls Contract is another sore point; early in 2010 a legal challenge to that contract was launched in the Quebec courts by Nalcor. Williams was irritated by these disputes, as well as by his perception that federal governments generally afforded Quebec preferential treatment over other provinces. Williams was not shy in sharing his assessment of Quebec with the public. In his June 2010 speech to the Canadian Club in Ottawa he made his views on Quebec abundantly clear.

Williams even jumped into New Brunswick provincial politics to fight Quebec. In 2009, New Brunswick Premier Shawn Graham and Quebec Premier Jean Charest announced a preliminary agreement for Hydro-Québec to purchase New Brunswick Power, a New Brunswick Crown corporation. That potential sale created considerable controversy in New Brunswick, and Williams immediately entered the fray. Other than going through Quebec, the only route for the export of Lower Churchill power is through the Maritime provinces. Williams saw any Hydro-Québec move into New Brunswick as a threat to that alternative. On that basis, he opposed the deal. He also pointed out to New Brunswickers all his province’s problems with Hydro-Québec, and raised doubts about whether the Quebec corporation could be trusted and whether the proposed sale would be in New Brunswick’s interest. Williams’ intervention reinforced local grassroots opposition to the Hydro-Québec plan. By early 2010, the deal was dead. Williams’ goal was achieved. Entering another province’s political arena was a bold high-risk move. It could have been perceived there as unwelcome outside interference.

Williams was also daring in his dealings with corporations that had substantial interests in provincial natural resources. In 2006, in reaction to the province’s demands for more local benefits, the proponents of the Hebron offshore oil field gave up negotiations and pulled their staff out of the province. The media were generally critical of Williams; some were dubbing him Danny “Chavez.” There were even local misgivings once the proponents closed their offices. Still, Williams stood firm. And, as the months passed and oil prices rose, there was a breakthrough. By the summer of 2007 there was a deal. Compromises had been made by both sides, but amid the fanfare of the announcement, Williams’ critics were largely silent. The multibillion-dollar Hebron development was a go, and Williams touted the fiscal and local benefits that would result. This reinforced the Williams mantra of “no more give aways.”

That same mindset came into play in late 2008. AbitibiBowater had just decided to permanently close its paper mill and related operations in the province. The provincial government reacted quickly. It passed legislation to take back all of AbitibiBowater’s timber and water rights and expropriate its hydro electric and other capital assets. There was provision for compensation for the latter, but not for the timber and water rights. In large part, those resource rights had been granted about a century ago in order to support the original developers of the mill; now the mill was to be no more, so the province was taking the concessions back. Constitutionally, the province had the authority to take such action; natural resources and property rights are under provincial jurisdiction. However, AbitibiBowater claimed these actions breached the North American Free Trade Agreement. To resolve that issue, the federal government, not the province, settled with Abitibi in 2010, paying some $130 million in compensation. Again, Williams had made a daring move and, somewhat embarassingly, the hastily passed legislation had actually expropriated more than was intended. Still, it was a move that met with widespread support at home. On the other hand, the feds were probably somewhat perturbed at having to bear the cost of the provincial policy. However, they did not complain, and this matter did not turn into another intergovernmental war of words with the Newfoundland and Labrador premier.

Williams’ hard-nosed approach to dealing with external parties carried over to his critics at home. From early in his tenure, he had established himself in firm control of his party and the provincial bureaucracy. Even beyond those institutions, however, he had little patience for those who raised questions or doubts about his strategies and goals. Journalists, talk-show hosts, commentators and representatives of various institutions and interest groups who raised questions or were critical of government policy were either dismissed or subjected to Williams’ powerful verbal onslaughts. Members of the tiny opposition in the House of Assembly were especially hard hit by his salvos, which could at times even question their loyalty to the province.

Remarkably, the leader of the official opposition, Yvonne Jones, maintained her poise in the House and has proven to be an effective critic.

Yet, despite his harsh treatment of local critics, Williams enjoyed consistently high approval ratings. Partly that was due to his success in defending the province’s interests, especially those involving natural resources. His determined leadership was also much admired. But beyond that, he was able to endear himself to many Newfoundlanders and Labradorians. His salary as premier was donated to local causes. He was widely available to speak to many community groups. He officially apologized to the Inuit of Nutak and Hebron for their forced resettlement in the 1950s, and he signed the New Dawn Agreement with the Innu. He was very supportive of Newfoundland and Labrador cultural activities and the arts, and had an appeal to Newfoundland nationalism. All this, and his willingness to appear on light-hearted television skits, notably on CBC’s This Hour Has 22 Minutes, served to enhance his widespread popularity.

Danny Williams leaves an impressive political legacy. When he took office, the province’s place in Canada, for want of a precise measure, was “last,” a characterization that had held since 1949. That changed during Williams’ tenure. The severe out-migration of the 1990s is over. The economy is doing well and employment is growing. The offshore oil industry is booming. GDP per capita is among the highest of the provinces, and per capita personal income is catching up with the national average. The provincial government’s credit rating has been upgraded a number of times over the past seven years, as its fiscal position improved considerably. Transfer dependency is no more. It is now a have province. It has ceased to qualify for Equalization since fiscal year 2008. Even including Atlantic Accord offset payments, federal transfers to the provincial government were only about 25 percent of total revenues in 2010. Largely as a result of oil revenues, the government was able to increase spending and reduce tax rates and still have surpluses. Even after the 2008-09 recession, there was a budget surplus; and the near-term outlook is for continued surpluses. In fact, the fiscal turnaround is so strong that the province will even cease to be eligible for offset payments after 2011/12. And despite the AbitibiBowater and Hebron issues, the province has adopted fiscal and regulatory measures that are decidedly probusiness. Of course, serious challenges remained at the time of Williams’ resignation: the unemployment rate was still above 10 percent; many rural areas were struggling; the fisheries continued to be beset with problems; and there was a considerable amount of accumulated provincial debt. Nevertheless, the improvements over Williams’ seven years in power have been transformative.

Of course, much of the improvement would have happened anyway. After all, increasing offshore oil and rising oil prices were not Williams’ doing. Some could even argue that his approach delayed some of the more recent expansions. However, delays in the interest of greater future benefits are sometimes more than worth it. Certainly all the credit for the 2005 agreement, assuring the province of at least an extra $2 billion ($4,000 per capita) in offshore revenues, goes to Williams and his battle with the Martin administration. Then there were his tough negotiating tactics and decisive actions regarding other resources, all aimed at getting more return for the province. He did not simply cruise along on the waves of petro dollars. His confrontational tactics and strategic use of the media got results.

Danny Williams leaves an impressive political legacy. When he took office, the province’s place in Canada, for want of a precise measure, was “last,” a characterization that had held since 1949. That changed during Williams’ tenure. The severe out-migration of the 1990s is over. The economy is doing well and employment is growing. The offshore oil industry is booming. GDP per capita is among the highest of the provinces, and per capita personal income is catching up with the national average.

Unlike many other politicians, Williams chose to leave politics before his time rather than after. What is equally surprising is that there was no real competition to replace him. Upon his hasty departure in December, Deputy Premier Kathy Dunderdale became interim premier. Dunderdale had been a member of cabinet from the first days of the Williams administration, and her background before entering provincial politics was in social work and municipal politics. At the time of Williams’ departure, she held the important cabinet portfolio of natural resources as well as being deputy premier. Perhaps as a sign of her leadership style, within days, the provincial government settled negotiations with the Newfoundland and Labrador Medical Association and with a small group of striking provincial government support workers; both disputes had been going on for many months.

Initially, Dunderdale said that she intended to serve as premier only until a new party leader had been chosen and that she had no plans to be a candidate. The deadline for filing nominations for the leadership was January 10, 2011. As that deadline approached, one by one, the more well-known likely contenders announced their individual decisions. Everyone opted out. No one was willing to run for the leadership of a party that is already in power; is highly popular; has fiscal resources enough to be lowering taxes, running surpluses and reducing taxes; and is almost certain to win reelection in 2011. Perhaps that lack of candidates was due to Williams’ abrupt and unexpected departure. No one was prepared for it. Moreover, since everyone had expected Williams to lead the party into the 2011 election and beyond, who would have dared to be actively organizing a leadership bid prior to November 25?

Most, if not all, of those who decided against running indicated their support for Dunderdale to stay on, and she reacted by cautiously indicating a willingness to reconsider her decision not to be a candidate for party leader. Then she was in! With no other contenders, apart from a person whose nomination was disqualified, Dunderdale will be the party leader. A Williams loyalist, she is likely to continue his approach to natural resource policy, to fiscal and social policy, and to advancing the province’s interests in Canada.

With Williams’ exit, the federal Liberal and Conservative parties and the federal bureaucracy will likely feel more at ease with his replacement; so too might officials in other provinces as well as some private sector executives who have dealings with the province. At the same time, Williams’ confrontational tactics, while very effective at times, likely had a limited shelf life; you can do a walkout or lower the flag only so many times. Still, the less intense demeanour of the new premier does not necessarily mean a softer position. As 2011 unfolds, it will be interesting to see whether the provincial Progressive Conservative Party under Premier Dunderdale’s leadership will have the same popularity and electoral success as Danny had.

Photo: ggw / Shutterstock