Canada’s failure to obtain a seat on the 2011-12 UN Security Council has generated an emotional response among the general public that is highly unusual in matters of foreign policy. (In the 2008 federal election, Canada’s political leaders held two televised debates, neither of which dealt with foreign policy at all.) Regardless of whether Canadians are disappointed with the lack of success in obtaining a council seat, or whether they are proud of the government for being unwilling, to paraphrase the Prime Minister, to compromise Canadian principles to satisfy the wants of rogue UN members, the quantity of debate and the passion associated with the results of the election campaign are unusual in a country whose political concerns are generally inwardly focused.

While many analysts have offered assessments of what went wrong (or right), for the most part, few have been asking the questions that might move Canada forward as the public’s interest subsides. This article, therefore, offers ten questions that are worthy of further exploration.

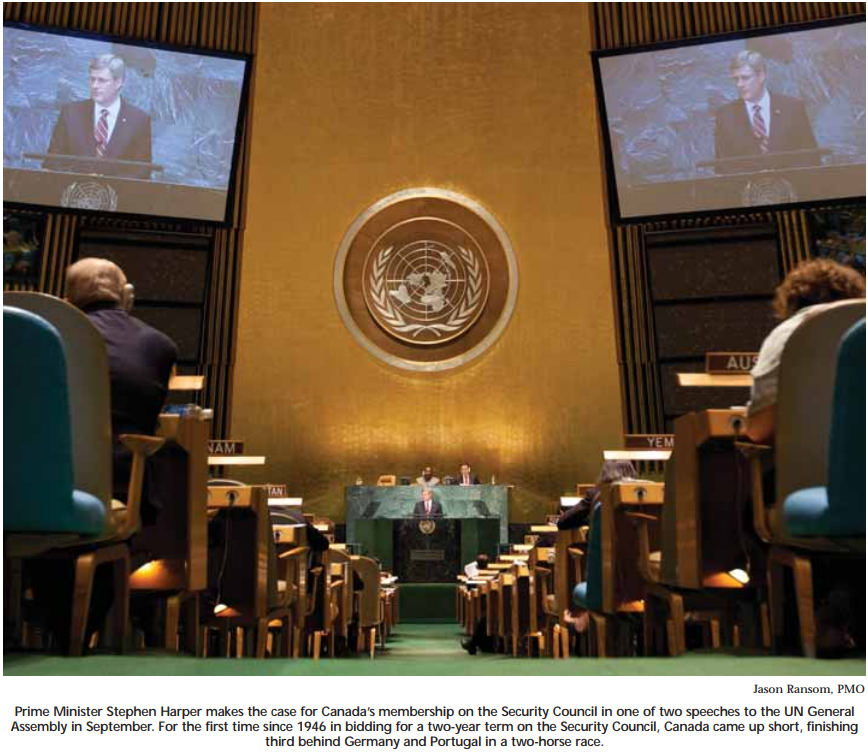

Question 1: There should be no denying that the campaign was a failure. Sources close to Foreign Affairs Minister Lawrence Cannon noted that Canada had secured written promises of 135 votes (8 more than Ottawa needed to be elected to the council on the first ballot), and yet in the first round of voting, only 114 states supported Canada’s candidacy. In the second round, that number dropped to 78. So what went wrong?

Analysts who claim to have the definitive answer should not be trusted. There is simply no way to measure the impact of the variety of administrative factors that might or might not have played a critical role in a vote that was taken by secret ballot. One can, however, wonder about a number of things: Did having three ministers in less than five years deprive Foreign Affairs and International Trade of the continuity of leadership necessary to pursue a prestigious international position effectively? Did Canada’s foreign service officials fail in their duty to speak truth to power and warn the government that Ottawa’s campaign was in trouble? Did the officials even know that there was a problem? Did the Canadian government’s decision to campaign for a seat without an explicit platform — a tactic that could be considered either a break from the successful campaign for the 1999-2000 seat or a return to the approach of previous campaigns — hurt or help? Did cuts to the hospitality budget of Canada’s permanent representative to the UN, John McNee, make a difference?

Certainly, the failure of the campaign is a problem. Perhaps more important, however, is that Canadians have shown little interest in determining the causes of that failure that might be dealt with in the future.

Question 2: About a week before the election last October 12, Liberal Opposition Leader Michael Ignatieff joined a chorus of left-leaning activists in questioning whether, based on the last five years of Conservative activity on the world stage, Canada in fact deserved a seat on the council in 2011. What could he possibly have been thinking in making comments that so blatantly undermined Ottawa’s candidacy?

Was Ignatieff trying to court the radicals? This would have been a rather foolish idea since extremists rarely vote Liberal. Was he following the advice of members of his communications team who have emphasized repeatedly that the Liberals must differentiate themselves from the Conservatives if they hope to convince Canadians that they should form a government? Perhaps, but differentiating oneself on foreign policy hardly makes sense politically, seeing as when the election finally comes, few Canadians will be making their decision based on the Liberals’ view of the Security Council.

What is clear is that Ignatieff was not thinking about Canada’s national interests. There is no way to explain how airing the nation’s dirty laundry on the world stage could possibly advance Canada’s international position. Moreover, Ignatieff clearly failed to realize that the council seat was Canada’s, not the Conservatives’, and that in compromising his country’s image abroad, he was not just hurting the Conservative Party.

Canadians need to find a way to reward their political leaders for putting the national interest ahead of petty partisanship. Until we do so, we are bound to experience more of these short-sighted, unnecessarily harmful political interventions.

Ignatieff clearly failed to realize that the council seat was Canada’s, not the Conservatives’, and that in compromising his country’s image abroad, he was not just hurting the Conservative Party.

Question 3: What was Foreign Minister Cannon thinking when he met with national representatives to the UN just days before the council election and discussed Ignatieff’s comments?

If, by demonstrating the lack of unity behind Canada’s bid for a council seat, Ignatieff’s musings were so detrimental, why did Foreign Minister Cannon make sure that every international delegate knew about them? Indeed, one would assume that if the appearance of national cohesion was important, Cannon would have either (1) gone out of his way to avoid any discussion of Ignatieff or (2) reached out to the Liberal leader in an effort to smooth over any domestic conflict in advance of the vote.

It is most unlikely that Cannon would deliberately sabotage Canada’s election campaign. Ruling this out, it is difficult to understand his motivations, unless one comes to the ugly conclusion that excessive partisanship has become so much a part of the conduct of contemporary Canadian politics that either Cannon could not help himself, or he felt powerless to ignore speaking notes from the Prime Minister’s Office ordering him to behave in such an inexplicable manner. Again, then, the politics of Canadian foreign policy appear to be out of control, and few Canadians seem to be asking what it will take to stop the situation from getting even worse.

Question 4: Shortly after the Prime Minister’s Office stopped suggesting that Ignatieff’s comments were themselves sufficiently harmful to cause approximately 50 international delegations to choose Portugal over Canada in the second round of balloting, Ottawa announced that, over the last five years, it had pursued a principled approach to foreign policy, and that if certain countries were uncomfortable with such principles and had punished Canada by not electing it to the council, then so be it. But if electoral defeat was an acceptable loss, why did the government make the campaign a strategic priority in the first place?

Clearly, the government did not consider the defeat an acceptable loss until after it had taken place, which leads to another critical problem in the contemporary Canadian political environment: somehow, it has become impossible to admit a mistake. Rather than conceding that the Canadian campaign was ineffective and seeking to figure out why, Ottawa went out of its way to provide excuses. Why is making a mistake such a problem? Has the Canadian public set standards for its political leaders that are simply impossible to fill? Or have Canada’s leaders underestimated the public’s capacity to understand that mistakes are made, and that good governments and strong leaders learn from them?

Question 5: Given the government’s recent effort to host the G8 and G20, an initiative that cost Canadians close to $1 billion, how can Ottawa now claim that a seat on the Security Council in 2011-12 was not critical to Canadian national interests?

Among the justifications for hosting the international summits were the benefits that would be incurred by Canada because of its active leadership in international diplomacy and because of the access Canadian negotiators would have to the most powerful world leaders. With this argument in mind, one might consider the composition of the Security Council in 2011. Members will include representatives from the US, the UK, Russia, China, France, Brazil, India, Germany, South Africa, Colombia and Nigeria.

In the present Security Council group are all of the BRIC countries, six nuclear powers, the leaders of NATO, eight G20 members, including five of the last six chairs, more than half of the G8, arguably the two most powerful states in Africa and the most powerful state in South America. How can the government justify the extraordinary expenditures that supported meetings of the G8 and the G20 and then argue at the same time that weekly, if not daily, meetings with the countries mentioned above are not important?

Perhaps the answer is that Ottawa cannot do so, credibly. Membership on the Security Council is important, just as hosting the G8 and G20 was a good, albeit expensive, decision. Countries like Canada, which lack the capacity to impose their will on the international community through brute military power, benefit from multilateral venues circumscribed by a set of norms that tend to limit great-power bullying. Just as Canada’s economic interests are better served by its active involvement in the G8 and G20, Canada’s security interests would be better served by consistent access to the representatives of the 2011 Security Council.

Question 6: Moving beyond Canada’s own circumstances, there are international ramifications of the election results worthy of more significant consideration. First, coming into the election, most experts were quite certain that a German seat on the council was guaranteed. After all, Germany was the third-ranked contributor to the UN’s budget, was active in Afghanistan and in peacekeeping throughout the world and had not alienated any particularly influential bloc of countries. Nevertheless, when the election took place, Germany received just 1 vote more than the minimum 127 that were necessary to obtain a seat. So what happened?

Did the Germans run a poor campaign? Was Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to allow her deputy to address the General Assembly in her place shortly before the vote so offensive to the General Assembly that anticipated supporters changed their minds? Does Germany have critics of whom popular analysts of international affairs are not aware? Had Canada been successful in its campaign, Germany’s vote total would likely have been major news. It still should be.

Question 7: On paper, Portugal was an improbable choice for the council. Its economy is not strong and it therefore has little that it can contribute to issues of international security. So what exactly did the Portuguese do right? And what lessons can Ottawa take from their success for future Canadian campaigns?

Indeed, there is tremendous irony in the Portuguese argument for a place on the council. To paraphrase, Portugal maintained that small, struggling states needed a voice, and the General Assembly should therefore elect Portugal, a state whose primary contribution would be direct evidence of the struggles being experienced by so many others. With what was at best a flimsy argument, given the seriousness of the challenges faced by the Security Council, the Portuguese managed to convince over 100 nations of their worthiness. As it becomes increasingly difficult to win election to the council, the federal government would be doing Canadians a disservice if it did not analyze the Portuguese campaign in detail.

In the present Security Council group are all of the BRIC countries, six nuclear powers, the leaders of NATO, eight G20 members, including five of the last six chairs, more than half of the G8, arguably the two most powerful states in Africa and the most powerful state in South America.

Question 8: Some would question whether any of questions 1 through 7 matter. Does it really make a difference to Canadian interests if Ottawa is absent from the Security Council debates?

In this case, both opponents and supporters of the UN can make reasonable arguments. When it comes to questions of security, at the strategic level, having Portugal on the council instead of Canada should not make a significant difference. The great-power veto will not be affected, Portugal and Canada would likely vote similarly on the majority of issues facing the council, and Canada’s contribution to UN initiatives will not be affected significantly by its exclusion.

At the diplomatic level, however, the difference is likely more significant, even if one must concede that there is no absolute way to measure it. Relationships still matter in the 21st century, and traditional methods of international diplomacy, while no longer sufficient to advance a state’s national interests, still make an important contribution to the development and implementation of foreign policy. It follows that the missed opportunity for Canada to connect regularly with so many powerful countries is a big one. One can never be certain of when Canada will need allies in the future, and missing a chance to sit on the Security Council clearly deprives Ottawa of a means of cultivating diplomatic relationships.

Question 9: How can any internationally oriented state take the UN General Assembly seriously after it chose to appoint Portugal to a council with the responsibility to take significant decisions on international security when Canada — the seventh-largest contributor to the organization, and a country with an interest and willingness to contribute actively to the promotion of international security — was available as an alternative?

States that have been disappointed with Canadian foreign policy of late had a legitimate means of expressing that discontent without compromising the credibility of the UN election process. They could have rejected Canada in the first round of balloting — marking the first time since 1946 that Ottawa had not been successful in its first opportunity — and then elected Canada in the runoff. That so many members of the international community supported Portugal in the second round is a regrettable reminder of how far away from effective global governance the international community remains.

The problem with the theory of global governance is not the UN; if the international community were to disband the organization, in time the former members would inevitably create a remarkably similar body to replace it. The problem is the states themselves. Until certain members of the international community come to accept that diplomacy requires give and take, and that pandering to a domestic audience on the world stage might gain points at home but ultimately leads to greater global insecurity, neither the UN nor any other multilateral body will deliver the results that the disillusioned expect. The UN is a space that allows representatives of the international community to come together. It remains up to those representatives to make the system work.

Question 10: Finally, where does Canada go from here?

The following two suggestions are admittedly much easier said than done. First, it is incumbent upon the government to admit that something went wrong. There is simply no good reason that Canada should have failed to win a seat on the Security Council. Ottawa had close to a decade to plan and execute its campaign. It had greater resources than Portugal. It had experience and expertise both within and outside of the government that should have been co-opted into the process.

Admitting that something went wrong is integral to the process of beginning to ask the questions necessary to move forward. Is it Canada’s diplomatic posture that should be adjusted, for example? Or is it the communication network between the public service and the minister of foreign affairs that is not meeting expectations? And how important should obtaining a seat on the Security Council be in terms of Canada’s international priorities in the future?

Second, the electoral failure, and especially the partisan divisions that it has encouraged, are evidence of the need for Canadians to take a more mature and less partisan approach to foreign policy in the future. The Conservatives inherited a campaign for a council seat that they were not particularly excited about from their Liberal predecessors. It is fairly clear that there was no continuity after the change of government even though Canada’s national strategic interests should not be affected by the party in power. If Canadians wish to have an international policy that is effective and makes a difference, they will have to develop a framework that can be supported by both legitimate governing parties. Such consistency will make Canada a better ally, a better diplomatic associate and a better development assistance partner.

Since these suggestions will likely be branded as unrealistic by the political class, one can only hope that some smaller steps are taken. For instance, Ottawa must stop taking pride in its diplomatic failure, and the opposition must desist from using that failure to accentuate the differences between Liberal and Conservative approaches to foreign policy. Moreover, if the leaderships on both sides are not ready to ask the hard questions, then they could at least move on to bigger issues. For one, is the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade properly equipped to lead Canada’s international policy-making apparatus in the 21st century? It does not seem to be. Perhaps it is time for a parliamentary, if not a national, dialogue about the future of diplomacy.

In summary, Canada’s unsuccessful Security Council campaign can and should be used to illustrate to the Canadian public that international policy is not easy, and that compromises often do have to be made. Until politics stops getting in the way of good policy decisions, however, it is difficult to envisage real progress.

Photo: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutterstock