A decade into the 21st century, and the world of 1999 appears to us through a golden glass of memory like an innocent childhood. When al-Qaeda brought down the Twin Towers, it was obvious that our world would change in many ways, and it did. Terrorist outrages punctuated the decade and defences against them are part of tiresome daily routines. Yet, after eight years of war, there is an informed body of expert opinion that al-Qaeda as a global and directed lethal adversary is mauled and discredited, basically confined to its refuge in the Pakistani tribal areas.

There is no disputing the life-changing impact of the traumatic decade of global jihadist terrorism. Terrorism remains a real threat but it sourced from a constellation of disconnected franchises in such places as Yemen, Somalia and the Maghreb, and via free-lance impulses from young disaffected Muslims. It is not appeased and certainly not forgotten but it is something we can recognize and defend against.

Meanwhile, something else was going on that was felt less immediately in private lives but that will probably have more enduring and far-reaching significance to the world. It is the rise of the Pacific region, transforming the shape and distribution of power in the world in ways beyond anything that idle dreamers about Islamic caliphates could have imagined.

The world has always been diverse but its power structures and conceptual frameworks had for a century and more been Euroand Western-centric. The Pacific rise has changed the facts on the global ground.

Having had its market assumptions trashed by a crisis of credit and competence, the “West” has been humbled, challenged and in many ways reduced in influence.

The year 2010 will see China overtake Japan as the world’s second-largest economy and surpass Germany as the world’s largest exporter. As we saw at the Copenhagen climate change summit, non-democratic and state capitalist China has joined the US as an “indispensable nation” for the resolution — or non-resolution — of any significant global issue. India, while being much less powerful than China, has also vaulted into the top ranks of the world order and become an essential decider.

These two countries share booming growth rates. They also share the shared ambivalent condition of being powerhouses as national economies, but still poor on a per capita basis.

Yet in most ways they are very different. China’s scathingly earth-bound political controls and ethnically singular aversion to non-economic forms of plurality seem in contrast with India’s raucous pluralistic democracy, which co-exists with multiple devotional faith in the spiritual world. Yet the vast majority of Chinese hold to the “ain’t broke, don’t fix it” attitude to their governance.

While officially testy with each other, China and India are economically increasingly integrated into a region in which Japan also retains considerable influence.

For North America, the rise of Asia is not an existential challenge in the sense of being a threat. Robert Legvold wrote in Foreign Affairs in early 2009, apropos of Russia, that it is the first time in 300 years in which there are no strategic rivalries among the great powers. There is competition, to be sure, and friction, but without competing military ambitions or lusts for imperial gain, aside from some enduring territorial and jurisdictional disputes at the margin.

The year 2010 will see China overtake Japan as the world’s second-largest economy and surpass Germany as the world’s largest exporter. As we saw at the Copenhagen climate change summit, non-democratic and state capitalist China has joined the US as an “indispensable nation” for the resolution — or nonresolution — of any significant global issue. India, while being much less powerful than China, has also vaulted into the top ranks of the world order and become an essential decider.

The US President has recognized these trends in the Pacific, obviously, and has chosen to engage with the main players.

Canada has been politically absent from Asia for the last few years. Prime Minister Harper made a better-late-than-never trip in late 2009 to try to put Canada back in the picture, economically, and to regain some influence in the area, but experts say the road back to any serious Canadian influence will be steep.

In principle, the validation of a more diverse world with multiple centres of power should be to the advantage of a middle power such as Canada, at a time of globalization, one of whose features is mass migration. Human and family ties with India and China are a distinct Canadian asset. But their conversion into influence at the state level will require much more than a few high-level visits back and forth.

How Canadians approach the world, and such issues as democratization in China that seemed to block the Canadian government from pursuing the relationship, is important to plot.

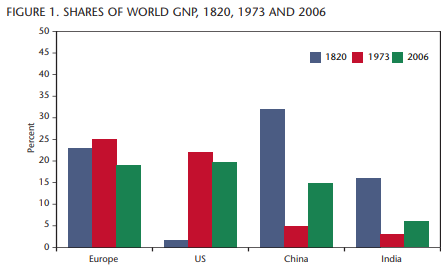

Former European commissioner Chris Patten has been predicting at least since 1999 that China would be bound to reclaim the position it once held as the world’s leading economic power. In 1800 China and India together accounted for about 75 percent of world production. Former Economist editor Bill Emmott helpfully charts the fall and rise in his excellent book Rivals, about China, India and Japan (see figure 1).

China and India both have very major challenges ahead, managing transformative growth and the distribution of benefits, as well as internal tensions. Neither country’s governance is as effective as each pretends; they are both less modern and mature than they would like us to believe, and corruption is a serious problem. But still, we can expect their economic progress to continue.

As rising Asia converges economically, will it not be at the expense of the “Western” economies? Are there not clear losers as well as winners here?

Simply put, there is no reason to believe so. Asian growth helps fuel the rest of the world economy; China’s stimulus package of $586 billion greatly helped to pull the US economy back to traction.

But despite recent proposed initiatives such as the East Asian Summit (which excludes the US), Asia is nowhere near becoming a single political and strategic space. Though it is the first time in history China, India and Japan have been “up” as economic powers in the world at the same time, balance-of-power politics apply to relationships among the three.

They aren’t strategic rivals but history has made them suspicious of each other. There are potentially dangerous frontier issues that have to be co-managed as their individual ambitions grate on neighbours’ nerves.

China and India share world views on major entitlement issues, insisting that global governance validate to a vastly greater degree the perspectives and interests of the newly risen, in membership privileges for select groupings and narrow decision-making circles.

In return, the US hopes that China and India will begin to participate in global decision-making with attitudes that go beyond self-interest, though the Chinese and Indians do detect a measure of hypocrisy here. Still, it is a justifiable hope and task that the uniqueness of this period’s absence of great power rivalry should be made to work for important global solutions. Will China and India go along? To guess at an answer, we need to look at each country’s particular journey.

Books and papers describing China’s rise and realities today and predicting its future rival the production of chopsticks for their consumption of wood products. Two excerpts capture the thrust.

UK sinologist Duncan Campbell, on BBC: “China has in two decades undergone a remarkable change unprecedented in human history in scope and rapidity — the first and second industrial revolutions and the knowledge revolution all at one time. There have been some bad years — 1989 — but the system is hold-

ing together.”

David Franklin, in the Economist’s The World in 2010: “China is identified as central

to every global issue in the coming year, from the economy to climate change and nuclear diplomacy… Whether China, with its multiple growing pains, to be a relaxed power or a prickly one will be a central issue.”

Many statistical expressions of change impress but five seem particularly eloquent:

- In 2009 China’s foreign reserves were the largest of any country in history: $2.2 trillion.

- In 2000, China sold 600,000 vehicles; in 2009, 15 million.

- The total of regular Internet users in China reached 338 million in 2009.

- There are now more English-speakers in China than in India, at 55 million.

- Polling, admittedly probably wobbly, indicates that 86 percent of Chinese believe China is headed in the right direction. (In the US, the comparable figure is 37 percent.)

Every writer and observer who knows China is stupefied by the extent of change; there are massive new cities, and old cities are made unrecognizable by new skylines, more apt today to shine in less polluted air.

China is balking at accepting submission to verified global quotas on carbon emissions, but internally it is pursuing a crash energy technology program to lessen its 80 percent dependence on coal. The government is adding nuclear reactors at a breathtaking pace and building wind farms at a rate that promises to make China the biggest user of wind energy within a few years and also the world’s leader in wind technology and manufacture.

Chinese economic impact on the world is already massively influential through the discipline the “China price” imposes on manufacturing costs everywhere.

How has China achieved all this at such a rate? Undoubtedly there are answers that are historic, sociological and even psychological in the makeup of the Han Chinese reality.

Many credit the ability of an authoritarian government to make far reaching decisions that can mobilize swiftly vast resources. As author Ha Jin wrote, “I always wonder who among our national leaders at the time had the foresight to discern the drift of history. How could he, or they, foresee that within 20 years English would replace Russian as the most powerful linguistic instrument for our country?” When Deng Xiaoping decided in the late 1970s that China would abandon the Soviet economic model and pursue a Chinese form of state capitalism, he set in motion a vast engine of growth.

Success depended on a vast pool of agricultural labour ready for internal migration to factories and new cities springing up everywhere, but especially in designated economic growth zones. To mobilize this critical resource, though, the regime had to lighten internal controls on what was still essentially a totalitarian society.

Economic performance and political governance were always connected. By the late 1980s a rapid and uneven pace of change indirectly led to a national crisis that came to a head in Tiananmen Square in 1989. The protests were motivated by student democratic idealism, but also by a festering sense of popular resentment that recent recession and inflation had exposed the management incompetence of a top-down regime.

The prime minister of China at the time was Zhao Ziyang. In the foreword to Zhao’s Secret Journal recorded during his years of house, arrest and recently published posthumously, China scholar Roderick MacFarquhar wrote, “Zhao confesses that as of the mid-1980’s, he was an economic reformer and a political conservative. Gradually he came to realize that without political reform, the economic reform program was in peril.”

Deng Xiaoping and most of the leadership judged the protests a dire and even existential threat to the regime, and Zhao was deposed for having argued a conciliatory line with the protesters.

But though Tiananmen was traumatic for the Chinese leadership, it rebounded in ways that were agile, resolute, and profound.

Fred Bild was Canada’s ambassador in the early 1990s, when the social effervescence that had begun to flourish in the universities had been shut off. Bild felt the effect of an anti-foreigner and hard-line mood in the regime. But by 1995, he discerned a second wave of reforms taking effect. People would be permitted to study what they wanted, choose their work or profession, change location or travel abroad.

The authoritarian regime’s capacity to make such fundamental changes reveals a strong pragmatic capacity when expediency insists. The leadership assessed the component parts of the Tiananmen movement and rewarded those that least threatened the Communist Party’s monopoly on political control.

Otherwise, the enormous expansion of China’s manufacturing capability could not have continued, and the regime would not have been able to promise prosperity and sound macroeconomic management of what was becoming a complex entrepreneurial economy of capitalists.

Propaganda shifted its focus to the benefits of radical economic reforms and the rewards of consumerism, as well as to patriotism and pride in the rise of China as a nation.

Over the course of the next decade, the regime delivered on these accounts. Moreover, authorities largely gave citizens back their private lives, even backing off the party’s traditionally narrow and moralistic view of sexual choices and other personal matters. Unquestionably, this is progress. The quid pro quo is that the Communist Party would not brook challenges to overall political control.

In the short term, it has seemed a politically successful bargain that has given the party a sense of legitimacy, in that there is broad acquiescence in the political status quo.

Meanwhile, more than a million Chinese have by now studied abroad. There is a cosmopolitan quality to urban Chinese life unthinkable even at the time of Tiananmen, when students were faxing around copies of the US Constitution. Students today get around Web site closures and web censorship enough to know pretty well the norms of governance elsewhere in the world.

One would think conditions would argue for loosening the party’s grip. Yet the current leadership under Hu Jintao seems obsessed by stability, and by the memory of Tiananmen.

As a prominent recent example, Tiananmen dissident Liu Xiaobo has been sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment for “incitement to subversion.” Liu has been leader of a movement, Charter 08, consciously modelled after the Charter 77 movement in Czechoslovakia that led to the 1989 Velvet Revolution. Its manifesto calls for freedom of expression, for the military to answer to the government and not to the Communist Party, and for multiparty elections, an independent judiciary and a truth and reconciliation commission.

In charging explicitly that “the current system has become burdened to the point that change cannot be avoided,” Charter 08 crossed the regime’s red lines.

Reporting on China for the BBC, New Zealand scholar Anne Marie Brady described training in obedience to authority that still starts with tots and goes right through the educational system. “By university, today’s students are generally loyal to party and state and accepting the whole propaganda package.”

Fred Bild suggests that among students and the young, protest may have to jump a generation from Tiananmen over the current career and lifestyle preoccupied youth to the next half generation.

China and India share world views on major entitlement issues, insisting that global governance validate to a vastly greater degree the perspectives and interests of the newly risen, in membership privileges for select groupings and narrow decision-making circles.

Meanwhile, Chinese authorities suppress any form of autonomist sentiment in the western frontier regions of Tibet and Xinjiang. While the two types of separatisms are quite distinct and founded on very different ethnic and religious aspirations, the Chinese leadership reacts to them with identical brutality and minimal sympathy or understanding. Significantly, they are the main locales for Buddhist and Muslim religious practice by the only significant racial minorities in a country that is ethnically 92 percent Han Chinese. Space doesn’t permit analysis here of Tibetan, Uighur and Chinese claims and counterclaims over forced cultural assimilation, but Chinese authorities are generally seen in the West as being excessively harsh, while the Chinese themselves consider they have exercised internal diplomacy and self-restraint.

But how should we view the experience of expatriate Tibetan scholar Ngawang Choephel, who returned in 1995 to record indigenous folk songs and who then spent seven years in prison for “espionage”?

On religion, the Communist Party is resolutely secular, though the Chinese Constitution tolerates state-controlled churches. The designation as a clear enemy of the state has been awarded the Falun Gong, a sect that sprang a few decades ago out of the qigong phenomenon of self-realization, using a combination of exercise and traditional Chinese mental disciplines and practice. Falun Gong’s ambit was wider, semi-religious, often under charismatic mentors, and came across to the defensive party officials as a threat to their monopoly on power. Whatever the reasons, the official persecution of Falun Gong members has come across as cruel and paranoid.

For how long can China maintain the duality Zhao Ziyang considered untenable 20 years ago, between economic reform and political rigidity?

Bill Emmott ably summarizes the two opposing views. A “resilient authoritarianism” thesis advanced by Andrew Nathan of Columbia University holds that the regime will remain in power for the foreseeable future. Supportive scholars argue that the government has shown itself to be “administratively competent and in many ways meritocratic,” and that corruption is not extensive enough to threaten its hold (Arthur Kroeber, editor of China Economic Quarterly). Canadian political philosopher Daniel Bell, now at Tsinghua University in Beijing, “argues that liberal democracy is anyway not the universal value that westerners claim it is, and that the Confucian tradition in China…may offer an alternative source of justice, human rights and accountability.”

Others argue that China’s archaic form of governance qualifies it as a “fragile superpower” (Susan Shirk, University of California, San Diego) and that the Communist Party is actually holding China back.

Observers inclined to inevitability of change see irresistible forces emerging from a more complex Chinese economy and society. A rigid authoritarian system cannot adjudicate the diversity of the many emerging issues and interests. Bill Emmott cites La Stampa commentator Francesco Sisci’s thesis (“Death, Taxes, and Democracy”) that the government will need to tax individuals to pay for improved services the public demands, and that in consequence, à la Boston Tea Party, they will have to concede representation.

A more transparent and democratic process is more apt to be accelerated by the Internet than by anything else. The Chinese authorities cannot hope to build a strongly competitive and innovative knowledge economy without enabling full access to the Web and to international contacts that by definition will weaken central controls. The wary surveillance and control of the Web that authorities maintain at huge cost are increasingly circumvented by various alternate server systems generated from outside China.

The quarrel with Google over censorship and Google’s threat to withdraw is worrisome. If China blocks Google from indexing Chinese domains, the once unified Internet could begin a process of disintegration. The crudeness of Chinese official dismissals of Google as a well-known site “for pornography” is such a throwback to earlier totalitarian communications that it causes worry about the bubble the leadership inhabits, and the quality of their judgment about the outside.

As to popular protests inside China, they are regularly taking place, often vocal and sometimes violent. In 2005, Chinese authorities acknowledged over 80,000 “mass incidents” a year, and they have not published figures since. Though localized and single-issue-based, the protests show that many people believe they are not getting the promised life-style benefits, nor legal rights and redress from a court system that is strictly controlled by party authorities. Quentin Somerville of the BBC reports the protesters are largely middle class although there have been significant mass petitions and protesters from peasants over land seizures and titles, and environmental harm. However, Somerville acknowledges that popular protests show little appetite for democratic reform of the kind sought by Charter 08.

In all this, two things are clear: Whatever political change occurs in China will occur because Chinese civil society and other internal groups make it happen, and Chinese authorities acquiesce in perceived self-interest, not because of remonstration from outside.

But democratic partners of China can use strategic relationships with the Chinese state to press authorities in private on the rights of democrats and human rights defenders.

How President Obama would deal with human rights in China was the object of intense speculation before his visit in November. Though he made a public issue out of freedom of access to the Internet, and spoke with vigour to a town-hall-type meeting with rather tame students selected for reliability by a host government worried that Obama would cast a seductive spell, he steered clear of encounters with human rights activists.

He focused on the goal of making China a long-term strategic partner. This approach paralleled his reaching out to Russia. To Obama, strategic engagement with the two permanent members of the UN Security Council is a paramount prerequisite for managing global peace and security challenges.

US NGOs gave him the benefit of the doubt. Republican critics blamed him for seeming “obsequious” to Chinese creditors. Obama refutes such charges: China can’t flip its huge holdings of US t-Bills without significant loss and is working to keep up its 10 to 12 percent growth rate for its own reasons, even if its stimulus is a boon to American suppliers.

China got out of the visit the prize of being treated as an equal. Whereas the US tendency prior to Obama had been to focus primarily on the need for support from China on terrorism and North Korea, Obama looked to the Chinese leadership to contribute to solutions on a range of key issues. He didn’t call for a G2, but he treated China as if there were one, on his trip and later in Copenhagen. US Ambassador Jon Huntsman explained to media, “There are really only two countries in the world that can solve certain problems.”

It must be the Chinese who have the proverb “Be careful what you wish for” because they seem a bit unsettled at finding their claim for equal status granted. They can see it comes with obligations as well as entitlements and bragging rights, including dialling down some of the recent shrillness in nationalist rhetoric.

Chinese behaviour in Copenhagen has angered European leaders. Clearly, the Chinese agitated developing countries to contest a deal. Stylistically, the Chinese performance was crude: sending a deputy minister to attend a meeting with President Obama may have had some inward demonstrative significance for the Chinese leadership, but to others, it looked small-time and politically inept.

Driven by national interest alone, the Chinese have always shied from being constrained by any notion of obligation to serve some sort of international “good.” For years, they took cover beneath Deng Xiaoping’s admonition to “nourish obscurity” and stay out of the limelight.

But “smile diplomacy” has proven inadequate as China’s interests spread in the world, creating for China a stakeholder’s interests in outcomes that are stabilizing, and also in a positive image. It has been pointed out that as long as Bush had the US in the world’s doghouse, China got a pretty free ride from any criticism. China’s economic model has attracted admiration, especially in Africa, where China’s stake in trade and in natural resource development is now dominant.

But with Obama having resurrected US popularity, China has to watch it does not become the new focus of world criticism for its internal repressions or for sidling up to dictators in Zimbabwe and Myanmar. Though there was hope that the Chinese leadership would want to avoid the reputation now of a self-interested international spoiler, it is not clear the authorities yet read it that way.

Despite a buildup of the military, Chinese foreign policy has in fact recently shown moderation, over Iran, North Korea, and border and territorial friction in the South China Sea and importantly with Taiwan, whose new president has a relatively forthcoming attitude to the mainland Chinese state. On key multilateral issues like currency relationships and carbon emission abatement, China talks tough but is in fact embarked on remedial policies at home.

Nonetheless, the tough talk is very much there and China does not fear challenging the notion of emerging international consensus when it sees fit to protect Chinese interests that are seen quite narrowly. The impression is that the Chinese leadership inhabits something of a bubble, inside of which public opinion outside China makes only a modest impact.

Obama’s priority on engaging China strategically seems the right call, and could be the apt corrective. It is one he is making toward India as well, although the situation in India is really very different.

The recent Indian rise has been almost as dramatic as China’s. Of course, though current growth rates are comparable, India does not have China’s power and capacity to mobilize resources in a command, if capitalist economy. China’s GDP is already three times the size of India’s, and there are no apparent prospects of the gap being closed, though a better measure of Indian performance is vis-aÌ€-vis its own recent past.

India is in many respects China’s polar opposite, a land of raucous pluralities, where central authority covers a cacophony of interests with a thin veneer of state. India is the world’s largest democracy, run in its own way, but accepting results of elections that are generally free and fair, and adapting peacefully to alternation of government. The press is assertively free. The individual reigns supreme, and at any given time, there are episodes of ongoing fasts purported as being to the death, though a dire end is usually forestalled by the intervention of changed facts, changed perceptions or the pressures of reason. Nonetheless, the society has multiple points of challenge to the hubris of power.

The tough talk is very much there and China does not fear challenging the notion of emerging international consensus when it sees fit to protect Chinese interests that are seen quite narrowly. The impression is that the Chinese leadership inhabits something of a bubble, inside of which public opinion outside China only makes modest impact.

Indian history since independence has known swaths of violence, mainly between Hindus and Muslins, and catastrophically at the time of partition itself, but there is also a fundamental basis of tolerance. Terrorist outrages such as the attacks in Mumbai or the devastating attacks on the Parliament in Delhi were not succeeded by vengeful reprisals.

Still, Indians such as Pankuj Mishra write of a “sense of permanent crisis.” India has preoccupations on all sides.

Since independence 60 years ago, the country has had constant tension with Pakistan as a national leitmotif that led to full-scale war on three occasions (1947-48 over partition, 1965 over Kashmir and 1971 over the secession of East Pakistan — which became Bangladesh — a split that India supported). Both countries remain in a state of constant preparedness for war and sling confrontational rhetoric back and forth, even if diplomats and others downgrade the likelihood of actual hostilities. War would, of course, represent a catastrophe for the US, which needs to keep Pakistan stable and focused on the Pashtun potential for disruption in both Pakistan and Afghanistan.

With China, there has been little historic connection. They also fought a Himalayan border war in 1962 that was a humiliation for India.

To the south, the relationship with Sri Lanka has been fractious. There is a fundamentalist Communist revolt smouldering in the north east.

India remains a poor country when one counts the number of its poor people. Despite the remarkable growth rates and the dramatic expansion of manufacturing, there are still 400 million Indians without electricity, including 75 percent of public schools.

This is a basic difference with China: deficiencies in public infrastructure. Both countries share high levels of corruption but in China the roads and high-speed trains get built despite it. Moreover, India spends about $400 a year on public schooling per student; China spends $2,700. And there is much education to be done: about half of Indian women are still illiterate.

Many people do feel left behind, but there is at least and at last a very strong force of growth leading the economy, driven primarily by the strength of private capital investment, and by the success of former finance minister and now Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in ditching the hidebound doctrines of Nehruvian Fabian socialism in favour of untrammelled Indian entrepreneurial instincts and appetites.

Nehruvian foreign policy was always laden with confrontation. “India doesn’t know what to do with its much-mauled nationalist soul,” writes Prabhu Chowla, editor of India Today. India systematically chose positions of exception from the policies of the major Western powers, especially to protest any perceived interference in a country’s internal affairs. Sometimes the principles involved become servants to Indian interests in jockeying for positions of influence with regimes such as Myanmar and Sudan, where there are oil and gas opportunities.

Nehruvian reflexes were at best distrustful of the US, but a rapprochement began under George W. Bush, whose administration negotiated a partnership in nuclear issues that signalled an end to India’s nuclear ostracism since the explosion of a nuclear weapon in 1974.

The Obama administration has courted Indian perspectives on a wide range of global and regional issues, much as with China.

US intuition is that a relationship of trust can come more easily with a democracy than with a non-democracy. A major goal is to translate this to the multilateral issues on which India has occupied a spoiler position in the past such as global trade negotiations and climate change.

David Malone, who was Canada’s high commissioner to India and who is now president of the International Development Research Centre, writes,

Prime Minister Singh often says that no country with hundreds of millions of poor can rationally think of itself as a great power. Nevertheless, as India’s economic and potential geo-strategic significance is increasingly obvious to all, it is cautiously re-positioning itself on the global stage as a key player on economic and financial issues and a meaningful one in the security sphere. (In all of this, Indian leaders are seriously constrained by the primacy of domestic politics in a vibrant democracy still in formation.) It is trying to outgrow its immediate neighbourhood, newly engaging with the USA, and seeking to manage a too often contentious relationship with China rooted in tension between cooperation on economic issues and competition in the realm of security and of relative influence in Asia and globally. That neither China nor India are crashing around the high table of international power and influence in boorish fashion should be greatly reassuring to the rest of us, as they reclaim the glory that has been theirs throughout most of recorded history. Western powers were not always historically so restrained!

Joseph Caron, who has uniquely served as Canada’s ambassador to Japan and China and now is high commissioner in New Delhi, learned in his 17 years in Japan to respect the importance of that country. “Japan, like the US, has tremendous industrial strength on which the rest of the world depends. You can never dismiss either country. You have to keep a close eye on the high end of Japanese industry — they have led the world and will again.” In his view, Japan has “the highest civilization in the world,” which provides a cushion during setbacks such as the current crisis surrounding Toyota call-backs.

Japan has watched the Chinese rise with official apprehension. The relationship with China on the state level has been coloured by the bad history of the 20th century and by a certain amount of ambivalence on the part of the previous Japanese government over the responsibility of Imperial Japan for war crimes in the 1930s and ’40s in China.

But on a business level the relationship has soared. In addition Japan has poured billions of dollars into development assistance to China. (The largest recipient of Japanese assistance is India.)

Japan’s new prime minister, Yukio Hatoyama, whose Democratic Party turfed the Liberal Democrats out of office after a half century, has proposed an East Asia Community centred on China and Japan that excludes the US, reflecting an upward adjustment to Japanese acceptance of the realities of the region, and a downward acceptance of a role vis-à-vis the US that Hatoyama considers “subservient.” Ultimately, Hatoyama sees a role for Japan as a sort of balancing power between China and the US, with a strong balancing relationship with India.

All in all, the Pacific is soaring in political and economic prominence and is changing beyond recognition.

Among China watchers and the engaged business community in Canada, there is much bitterness over Stephen Harper’s negative approach to China. Most maintain he has done real damage to Canadian interests and influence.

Stephen Harper must have had his reasons to ignore China for three years. Undoubtedly, disapproval of China’s human rights performance was central. The closed-door human rights dialogue that Prime Minister Jean Chrétien had inaugurated in 1995 was dismissed as ineffective. The overall strategic partnership that Paul Martin had cemented with President Hu Jintao in 2005 was not pursued.

In what was a rookie error of miscalculation and hubris, Harper loudly took up the cause of a Uighur mullah who had emigrated to Canada and whom the Chinese imprisoned for purported separatist activity. Harper’s self-confident charge incontestably alienated the Chinese leadership while obtaining nothing for the hapless Huseyin Celil, who remains in jail.

No Canadian ministers visited China for a couple of years. Canada’s share of the trade of the world’s largest trader fell to 1 percent from 2 percent.

As Canada dropped out of multilateral politics internationally (except for Afghanistan, and a position as the WTO’s leading per capita launcher of trade complaints against other WTO members), the idea of China and India becoming vital to the resolution of global issues seemed of remote interest to the politically preoccupied minority government. The Harper team clung to the G8 until long past its sell-by date and didn’t seem to grasp the essentials of a modern state in a complex and changing world. Says Wenran Jiang of the Woodrow Wilson Center: “It is unprecedented for any G8 leader to simply stop engaging the Chinese at the highest levels.”

The Canadian trajectory can only go in one direction — up. It will take assiduous application to get back to the level of relationship enjoyed during the Chrétien era, building back cooperative projects in “institutional modernization,” exchanges of experts and scholars, and a vigorous program of public diplomacy and outreach on the part of Canadian diplomats, including to officials of the Communist Party.

An effort to recover came in the form of the Harper visit to China in November. At its outset, Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao delivered a stiff rebuke: “For years, the China-Canada relationship had been quite close. But the recent couple of years — and this is not what we would like to see — relations between the two countries were estranged, thus affecting trading and personal exchanges…I hope that we are able to fix our problem of mutual trust.”

Belatedly, Harper seems to recognize that a strategic relationship with China presents the opportunity to support China’s democrats, and that in any case, China’s importance globally and potentially to Canada argues for tending to the relationship politically.

All this indicates that the Canadian trajectory can only go in one direction — up. It will take assiduous application to get back to the level of relationship enjoyed during the Chrétien era, building back cooperative projects in “institutional modernization,” exchanges of experts and scholars, and a vigorous program of public diplomacy and outreach on the part of Canadian diplomats, including to officials of the Communist Party.

India is another story. Joseph Caron, who is able to make comparisons, finds that among elites there is a natural welcome for Canada and Canadians in India, a function of the Commonwealth history Canadians disparage in part, and of the extensive family ties that have built up over the last 30 years, so well expressed by Canadian authors Rohinton Mistry, M.G. Vassanji and Vikram Seth Canadian offices in India are proliferating, and there is no question that among our most effective ambassadors are many dualcitizen-entrepreneurs, as well as Indian scholars who specialize in Canadian studies.

Business is burgeoning. The bad feeling that persisted over the years after the 1974 Indian nuclear explosion — enabled by secret diversion of fissionable materials from the CANDU reactor provided under bilateral cooperation — has dissipated, and Stephen Harper signed a Canada-India nuclear cooperation agreement during his recent successful official visit.

That India is a democracy certainly helps as well. By contrast, governance remains a problematic issue with China, despite strategic engagement. In North America and Europe there is public resentment of Chinese mistreatment of individuals on political grounds and of repression of minorities. Should China’s growing integration with increasingly democratic and globalizing international society indeed lead to the internal relaxation of repression of democratic activists, a closer bond with democratic publics elsewhere will emerge. Otherwise, the relationship will remain below its potential and could become quite difficult.

Overall, Asia’s rise permits optimism about the prospects for greater stability in the world, provided that the Chinese leadership develops greater sensitivity to opinion outside China.

If thoughtfully and consistently guided, Canada could have an important part to play in the unfolding narrative and the integration of China and India as key partners in global decision-making. These do indeed shape up as the outstanding positive developments in the world thus far in the 21st century.

Photo: Shutterstock