On April 1, 2009, Nunavut Commissioner Ann Meekitjuk Hanson laid out the legislative priorities and vision of the government of Nunavut in Tamapta, an ambitious document whose title literally translates as “all of us.” Speaking almost 16 years after ratification of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (hereafter the Nunavut Agreement), which promised to establish Nunavut, and on the 10th anniversary of the formal creation of the territory with its own territorial government, she noted: “In building Nunavut, the challenges have sometimes been as daunting as the opportunities have been promising.” Quite so.

When the Nunavut land claim was negotiated in the 1970s and 1980s, Inuit and the Government of Canada disagreed on whether and how political development should be included. At the same time, Aboriginal self-government was discussed in three constitutional conferences that failed to establish in the newly patriated Canadian constitution the right of Aboriginal peoples to govern themselves. It was not until 1995, two years after the Nunavut Agreement was ratified, that the Government of Canada adopted a policy recognizing the inherent right of Aboriginal self-government and permitted this topic to be addressed in comprehensive land claims negotiations.

Notwithstanding the unresolved national debate about Aboriginal self-government, the lack of supportive precedents and numerous policy obstacles, Inuit refused to countenance an agreement that separated land rights and political development. Reflecting their overwhelming majority status in the eastern Arctic, Inuit conceived the Nunavut project as a combination of land rights and self-government, through division of the Northwest Territories (NWT), to establish a Nunavut territory with its own public government.

The 25-year Nunavut campaign involved negotiation, litigation, political action, community consultation, appeals to the Canadian public, two NWT-wide plebiscites on the concept of dividing the NWT and on the actual dividing line, an Inuit-wide ratification vote in 1992 and parliamentary votes in 1993. Pursuant to article 4 of the Nunavut Agreement, the Government of Nunavut came into being on April 1, 1999.

Behind these dry facts are numerous and often very colourful personalities, federal policies on northern political development ignored or circumvented, appeals to national pride and conscience, and significant interest on the part of the press in Canada and in the United States and Europe. It is no exaggeration to say that the Nunavut project changed the map of Canada and the perception of many of the nature of the country.

Ten years after the creation of Nunavut, it is interesting to recall the key steps taken to get there and the obstacles remaining on the road to the successful implementation of the Nunavut Agreement.

In his recently published biography, John Amagoalik, who for many years was intimately involved in the Nunavut project, recounts how in the 1960s many young Inuit were taken from their families to be educated at the Vocational Institute in Churchill, Manitoba. Several of the Inuit who in the 1970s initiated the Inuit land claims “movement” and the Nunavut project first met in Churchill during a period of national and international ferment that gave rise to Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” and Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s “Just Society.”

For many Inuit this was the first time they had stood up for, defended and advocated their Aboriginal rights. The newly educated and increasingly politically active Inuit leadership rejected Jean Chrétien’s 1969 White Paper proposing assimilation of Aboriginal people into the larger Canadian collective. They saw the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act as a more appropriate model for Inuit and Arctic Canada.

Several of the Inuit who in the 1970s initiated the Inuit land claims “movement” and the Nunavut project first met in Churchill during a period of national and international ferment that gave rise to Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” and Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s “Just Society.”

With the establishment in 1971 of Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (ITC) as a national advocacy organization for Inuit and of regional Inuit associations by the mid-1970s, Inuit in northern Quebec, Labrador, the eastern Arctic of the NWT and the Beaufort Sea had political institutions and were able to make coherent demands to the governments of Canada, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador. The 1973 Calder decision by the Supreme Court of Canada on the land rights of Nisga’a in British Columbia prompted the Government of Canada to renew negotiation of treaties with Aboriginal peoples whose title to land had not been superseded by law or ceded to the Crown through historic treaties, which was the case in most of British Columbia, the territorial North, northern Quebec and Labrador. Hydro-Québec’s plans for massive hydro development in the northern portion of the province precipitated fast-tracking of the negotiation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement with Inuit and Cree, which was concluded in 1975.

It was in this broad and rapidly evolving political and legal context that the original Nunavut proposal was prepared by ITC in 1975. Negotiations with the Government of Canada were slow and hesitant; the parties had very different views as to the scope, intent and preferred outcome of the exercise. To speed up the process, the mandate to negotiate the Nunavut land claim was withdrawn from ITC in 1982 and given to a newly established Inuit organization, the Tungavik Federation of Nunavut (TFN), created for the sole purpose of negotiating a modern treaty with the Government of Canada.

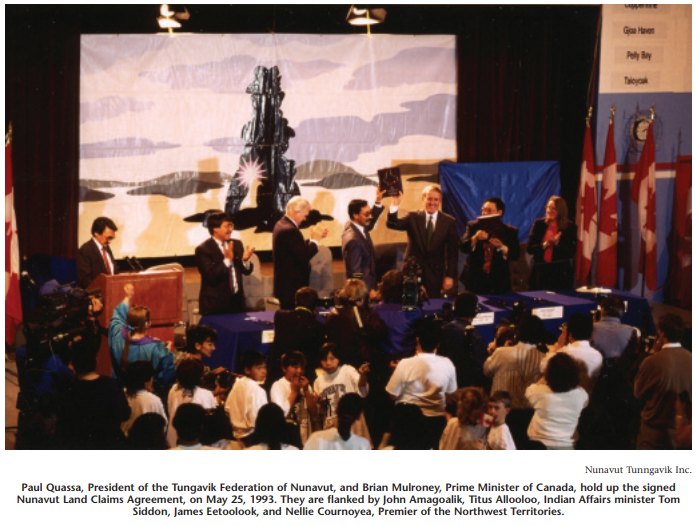

Negotiations continued through the 1980s, with a hiatus in 1985 and 1986 that resulted in the federal cabinet approving substantial changes to the comprehensive land claims policy under which the negotiations were conducted. An agreement in principle was signed in Igloolik in April 1990, and the final agreement was signed in Iqaluit on May 25, 1993, and ratified by Parliament only weeks later.

The 42 articles and nearly 300 pages of the Nunavut Agreement, which is a comprehensive land claims agreement or modern treaty, define the terms and conditions of an exchange. In return for the rights and benefits defined in the agreement, Inuit agreed to cede, release and surrender to the Crown in Right of Canada all their claims, rights, titles and interests to land and waters in the settlement area, and vouched never to undertake legal action based on those claims, rights, title and interests. As a result, the Government of Canada obtained legal certainty of ownership of land and natural resources in more than 20 percent of the country, enabling it to issue to third parties unencumbered rights to develop those resources.

The Inuit of Nunavut obtained a wide variety of constitutionally protected rights and benefits, which are summarized in box 1.

Article 4 of the 1990 Nunavut agreement in principle affirms the “support in principle” of Canada and the NWT for the establishment of Nunavut, but “outside the claims process.” It also includes a commitment to hold a territory-wide plebiscite on the boundary and to negotiate an agreement on the division of powers. This was the first time that political development was addressed in cold, hard type in a comprehensive land claims instrument, albeit not a final agreement. In hindsight, this was a major step forward for Inuit. TFN was aware that if it successfully navigated the conditions, particularly the territory-wide boundary plebiscite, the Nunavut project would gain considerable, perhaps unstoppable political momentum and public support. This is precisely what happened.

Article 4 of the 1993 final agreement was quite explicit in stating: “The Government of Canada will recommend to Parliament as a government measure, legislation to establish, within a defined time period, a new Nunavut Territory, with its own Legislative Assembly and public government, separate from the Government of the remainder of the Northwest Territories.”

This article also provides for TFN, the Government of Canada and the Government of NWT to negotiate a political accord on the timing of the establishment of Nunavut and the powers and financing of the new government. Unlike the other provisions of the Nunavut Agreement, however, this article was not accorded constitutional protection enabling the Government of Canada to continue to claim that its policy distinguishing land rights from political development remained intact. Be that as it may, the narrow “win” by Inuit in the May 1992 NWT-wide plebiscite on the division boundary, the political accord agreed to in early 1993 and the formal ratification by Inuit and the Parliament of Canada of the Nunavut Agreement later that same year opened the way for the establishment of the Nunavut Implementation Commission to plan the creation of the new government, which was formally established on April 1, 1999.

How did it prove possible for Inuit, who were enfranchised federally only in 1960 and who were largely semi-nomadic until the early to mid-1960s and had very few formally educated leaders, to negotiate a modern treaty with the Government of Canada that addressed land rights and political development and that literally changed forever the face of Canada?

The promise in article 4 of the Nunavut Agreement to create the new territory was complemented by article 23, which aims to “increase Inuit participation in government employment in the Nunavut Settlement Area to a representative level.” Inuit form approximately 85 percent of the population of Nunavut, and this article promises that at some future but unspecified date they will enjoy 85 percent of the government positions in the territory. This objective has generated considerable comment.

How did it prove possible for Inuit, who were enfranchised federally only in 1960 and who were largely semi-nomadic until the early to mid1960s and had very few formally educated leaders, to negotiate a modern treaty with the Government of Canada that addressed land rights and political development and that literally changed forever the face of Canada? Drawing upon our personal experience in the negotiations, we offer the following explanations.

- Inuit politicians and negotiators were consistent in their vision for the future and displayed patience and tenacity in their demands to achieve this future.

- Inuit politicians representing the three regions of Nunavut — Kitikmeot, Baffin and Keewatin — remained united throughout the negotiations, including when there were tensions and uncertainty over drawing the boundary to separate the Inuit and Dene land claims settlement areas that could have resulted in the regions being split into sub-Nunavut, regional settlements.

- There were close and cooperative relations between staff, many of whom were kabloona (white), and Inuit politicians and negotiators.

- The parties were willing to compromise on issues the Government of Canada considered to be matters of principle, such as the Crown retaining title to most of the subsurface, and the boundary separating the Inuit and Dene land claims settlement areas.

- A forward-looking and practical approach was adopted that aimed to avoid embarrassing the Government of Canada for past mistakes, such as the involuntary relocation of Inuit from northern Quebec to the High Arctic islands in the 1950s, but rather to use negotiations to plan a positive future for Inuit within the Canadian framework. Inuit suggested they were joining Canada at a time when many in Quebec said they wanted to leave.

- The focus was concentrated on the Nunavut project through the establishment of TFN, whose mandate and sole purpose was to negotiate an agreement with the Government of Canada.

- There was a willingness and ability to draft provisions and respond quickly to the positions of the Government of Canada in order to “drive” the negotiating process.

- Relatively few third-party rights and interests to land and natural resources were subject to negotiation.

- The process was aided by the fact that in 1986 the Government of Canada adopted a Comprehensive Land Claims Policy that broadened the rights and benefits and narrowed the requirement to cede Aboriginal title through negotiated agreements.

Ottawa’s close attention was required if the Nunavut project was to move in a reasonable amount of time from an agreement in principle to a final agreement. In that sense, the collapse of the Dene/Métis Final Agreement in 1990 probably assisted Inuit in that it brought the Nunavut project to centre stage at a time when policy-makers in Ottawa needed to provide direction on the issue of political development.

We suggest, as well, that the Government of Canada’s negotiators approached their task with professionalism, diligence and creativity. While ministers of Indian affairs and northern development came and went during the 1980s, the federal chief negotiator, Tom Molloy, a Saskatoon-based lawyer, and the senior negotiator, Barry Dewar, a career civil servant, stayed with the process for years, providing continuity and corporate memory that spanned governments of different political persuasions. On the ratification of the Nunavut Agreement, Molloy correctly characterized the agreement as an “achievement shared.”

The Nunavut project also benefited from personal commitment on the part of key federal politicians (although this is difficult to evaluate). David Crombie, for example, was a keen Nunavut supporter during his tenure from 1984 to 1986 as minister of Indian affairs and northern development. His successor, Bill McKnight, obtained cabinet approval for reforms to the land claims policy that were first proposed by Crombie, including the application of provisions to the offshore, without which the Nunavut Agreement could not have been finalized.

Tom Siddon, another Indian affairs and northern development minister, signed the Nunavut agreement in principle in Igloolik in April 1990. Seeking to build connections with him, Inuit leaders took him and his spouse out on the land, where they slept on caribou skins in an iglu on the sea ice. On his return, he had supper with Inuit leaders and told them that they could count on his ongoing support for their project. He was still minister in 1993, and he personally called Prime Minister Brian Mulroney to recommend that the Government of Canada support both the land rights and the political development provisions of the final agreement. In 2005 he told one of the co-authors of this article importance of this experience on the land and of his deep respect for the Inuit leaders, negotiators and elders. Clearly, personal relations count for something in the world of policy, legislation and negotiations.

Many urban Canadians who have never been to the North have a positive or stereotypical image of Inuit that, in a very general sense, supported the Inuit intent to negotiate an agreement on land rights and political development. Inuit leaders characterized themselves as proud Canadians who support Canada’s Arctic sovereignty, which contributed to this image. Indeed, the Inuit contribution to Canada’s Arctic sovereignty is referred to in the preamble to the Nunavut Agreement. In short, if the Government of Canada could not conclude an agreement with Inuit — proud Canadians who stood up for Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic — with whom could it do so?

The implementation of the Nunavut Agreement raises issues and challenges that are very different from those faced in negotiating it. In the Government of Canada’s Comprehensive Land Claims Policy there is only one sentence on implementation, which requires that an implementation plan be in place upon ratification of settlements. We can attest from personal involvement that implementation was rarely discussed during the negotiation of the agreement.

The implementation provisions of the final agreement provide for a Nunavut Implementation Panel of federal, territorial and Inuit representatives, which is to “oversee and provide direction on the implementation of the Agreement.” Unfortunately, this body has proven largely ineffective, in part because the parties disagreed on the nature of key obligations and because of the inability of federal representatives to make or even accede to decisions.

A detailed 10-year implementation plan with contractual status was negotiated in 1992, entirely apart from negotiation over the final agreement; understandably, it attracted little political interest at the time. In order to deal with funding for the boards to manage wildlife, land, water and natural resources, and to identify who should do what to implement specific obligations, negotiators had to invent the assumptions upon which to base financial forecasts and commitments.

The renegotiation and renewal of the implementation contract to cover the period 2003 to 2013 has proved painful and unsuccessful, leading some to suggest that the Government of Canada had virtually lost interest in implementing the Nunavut Agreement and was concentrating on negotiations elsewhere.

The very breadth and conceptual ambition of the agreement has created implementation challenges. Huge changes were required in educational infrastructure to enable Inuit to develop the skills that are needed so they can assume the implementation positions in newly established Inuit institutions, resource management boards and the government of Nunavut. It is sobering to recall that in order to attain a degree or a professional qualification, with the exception of those for a few professional programs such as nursing, people in Nunavut still have to go south to attend university. Standards in primary and secondary schools in Nunavut are still well behind the national average, and the drop-out rate is well above the national norm.

Inuit are struggling to come to grips with the pace of social, economic and cultural change, and this struggle is manifested in the high rates of social pathologies such as suicide, drug and alcohol abuse and spousal assault.

Notwithstanding this difficult context, an independent review of implementation from 1993 to 1998, published in 2000, concludes that of 193 specific obligations, 98 were “substantially complete,” 46 were “partially complete” and 49 were “largely unmet.” These bald figures tell only part of the story. Relatively simple, one-off tasks such as the transferral of cash compensation and land to Inuit had been carried out on time, but the review reports significant problems in the implementation of “softer” obligations that require innovative, coordinated action on the part of federal agencies. The review team reports “a pattern of missed deadlines and slow starts, a lot of unproductive and extended discussions, backsliding on obligations, loss of corporate memory and capacity, and the consumption of resources without a full result.” The report recommended that the Nunavut Implementation Panel be reinvigorated, and it urged the parties to agree on the panel’s “central role in managing the implementation effort.” But from a standing start this was, perhaps, a mildly encouraging beginning.

The second independent review, which deals with implementation from 1999 to 2004, was published in 2006. It reports a number of accomplishments, such as the “inclusive drafting” of legislation to implement the wildlife provisions and the conclusion of impact and benefits agreements that cover national parks and Nunavut’s first diamond mine, but it raises major questions about the ineffective resolution of disputes between the parties. Covering the start-up period of the government of Nunavut, the review identifies several barriers to effective implementation. These include differences in interpretation regarding objectives and obligations, disputes over funding, a lack of collaboration and the absence of a process to monitor implementation. Once again, it recommends reinvigorating the Nunavut Implementation Panel and, tellingly, it urges the Government of Canada to increase its implementation accountability, saying: “The issue of trust, at least in terms of trusting the Government of Canada, is that the process itself conveys no certainty or accountability to the parties involved in working through problems and developing solutions.”

The renegotiation and renewal of the implementation contract to cover the period 2003 to 2013 has proved painful and unsuccessful, leading some to suggest that the Government of Canada had virtually lost interest in implementing the Nunavut Agreement and was concentrating on negotiations elsewhere. It was frequently alleged that the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND) could not get other federal agencies to fulfill their obligations under the agreement. Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI), the Inuit organization implementing the Nunavut Agreement, suggested that the mandate of the federal government’s implementation contract negotiator was inadequate and was, in any event, committed to the status quo of the first implementation contract covering 1993 to 2003.

The federal government’s blanket refusal to agree to arbitrate disputes, as provided for in the agreement, epitomized a growing gap between it and NTI. Conciliation by former justice Thomas Berger in 2006 proved unsuccessful. NTI agreed to it but the Government of Canada never formally responded to his report, which recommended a vigorous commitment to bilingual Inuktitut/English education to enable Inuit to develop the capacity to fully benefit from the Nunavut Agreement.

In 2003 NTI was instrumental in the formation of a coalition of First Nations and Inuit organizations that had modern treaties to jointly press the federal government to adopt a policy to fully implement comprehensive land claims agreements and to alter the machinery of government to ensure the adoption of “whole of government” approaches. In 2004 NTI petitioned the Commissioner of Environment and Sustainable Development in the Office of the Auditor General of Canada to examine the failure on the part of DIAND to implement the environmental and socio-economic monitoring provisions of the agreement. Soon afterward, a formal audit of implementation of the Gwich’in, Nunavut and Sahtu agreements by the auditor general of Canada supported the coalition’s analysis and position.

The Nunavut Agreement was a triumph of political statecraft, and while much has been accomplished, its full promise has not been realized. In 1993 the expectations that the Nunavut Agreement would “solve” difficult social and economic problems were probably too great. Nevertheless, the agreement does provide many tools that the Inuit of Nunavut, the Government of Nunavut and the Government of Canada can apply to address challenging public policy issues.

In the second half of 2005 representatives of the coalition met regularly with representatives of federal agencies to jointly draft an implementation policy. These negotiations were terminated by the new government immediately following the January 2006 federal election. The Senate Committee on Aboriginal Affairs held formal hearings in late 2007 and early 2008 into the implementation of modern treaties. The committee heard the same story of unfulfilled obligations and foot-dragging by the Government of Canada from each and every coalition member. NTI was a particularly prominent and voluble witness.

These various experiences prompted NTI to file a lawsuit in the Nunavut Court of Justice in December 2006 seeking $1 billion in damages for alleged breach of contract by the Government of Canada.

NTI’s statement of claim, posted on its Web site, is very broad and reflects the Inuit view of the substantive, procedural, financial and other failures by the Government of Canada to fulfill its duties and obligations, which were so painfully and meticulously negotiated from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. NTI President Paul Kaludjak did not mince words when filing the suit:

The Government of Canada keeps Inuit dependent and in a state of financial and emotional despair despite promises made when the Nunavut Agreement was signed in 1993. The Government of Canada is not holding up its end of the bargain. Canada got everything it wanted immediately upon signing the Nunavut Agreement. Inuit are still waiting for full implementation of the Agreement.

The Nunavut Agreement was a triumph of political statecraft, and while much has been accomplished, its full promise has not been realized. In 1993 the expectations that the Nunavut Agreement would “solve” difficult social and economic problems were probably too great. Nevertheless, the agreement does provide many tools that the Inuit of Nunavut, the Government of Nunavut and the Government of Canada can apply to address challenging public policy issues.

The agreement is best viewed as a marriage and not a divorce between the Inuit of Nunavut and Canada, and like all marriages, it requires care, attention and commitment on the part of both partners. It is difficult, however, to see how the agreement can be used to full advantage unless and until the Government of Canada departments that have implementation obligations commit themselves firmly to achieve them, and do so in a co-ordinated way.

Whether the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development has the ability and clout in Ottawa to ensure a “whole of government” approach needed to implement the Nunavut Agreement and other modern treaties is very much an open question. Certainly the Land Claims Agreement Coalition concludes that it does not, and it recommends an independent agency be established through a cabinet-approved modern treaty implementation policy to persuade, encourage and cajole federal departments to implement modern treaties and to audit and report on their performance. Without this type of policy commitment, modern treaties, including the Nunavut Agreement, are unlikely to be fully implemented.

Photo: Shutterstock