The Great Recession signalled a pivotal turning in the global and continental balance of economic power. More than anything else, it crystallized the fact that the economic strength of the United States, which was without rival at the turn of the millennium, is threatened from both within and without. In the past this would justifiably have sent shivers up Canadians’ spines, since it would have implied weakness in Canada as well. However, the rise of China as an important pole of economic power has important positive implications for Canada, both in terms of its role in the global economy and in Canada-US relations.

From within, the credit-driven housing bubble and bust has sapped US consumers of their purchasing power, forced retrenchment in order to get household balance sheets in order and contributed to an army of more than 15 million unemployed, underemployed or discouraged workers. The financial meltdown and recession also decimated the already fragile American public finances, resulting in record deficits and debt that will be exacerbated by demographically driven demands on Social Security and Medicare in the coming decade and beyond.

As a result, the United States is lagging, rather than leading, global economic recovery for the first time since the Great Depression.

From without, China has emerged as a global economic engine in and of itself. At the beginning of the 2000s, point China made its presence felt in global export markets upon entry into the World Trade Organization in December 2001, but its growth prospects were intimately tied to the hunger in the industrialized countries (primarily the United States) for low-cost high-quality goods across a wide spectrum of industries: most experts agree that export growth accounted for more than half of total GDP growth in China through the 2000s expansion. This has threatened US manufacturers via offshoring and import competition. The latter has also caused headaches for Canadian exporters in a growing number of industries.

But contrary to the fears of some, the Chinese economy did not implode during the 2008-09 global recession. GDP growth, which averaged just over 10 percent per year from 2000 to 2007, slowed only slightly, to 9 percent, during the recession and is forecast to average close to 10 percent for the next five years. In essence, the sharp drop in exports to the US and elsewhere was almost completely offset by strong growth in domestic demand. While this growth is partly due to government fiscal stimulus in the form of large infrastructure projects, it has also been sustained by rapid increases in wages and purchasing power.

The transition from a unipolar to a bipolar economic world has tectonic implications for Canada’s economic relationship with the United States (and the rest of the world for that matter) along several dimensions, with Canada holding the upper hand in most respects.

The most important shift is with regard to energy and natural resources. China is at a resource-hungry phase of development — with 10 percent of global economic activity, it accounts for nearly 40 percent of demand for industrial metals and 10 percent of demand for crude oil. Chinese demand for crude oil in particular is expected to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Nonetheless, the crash in commodity prices sparked concern that the boom was an aberration brought about by misguided speculation.

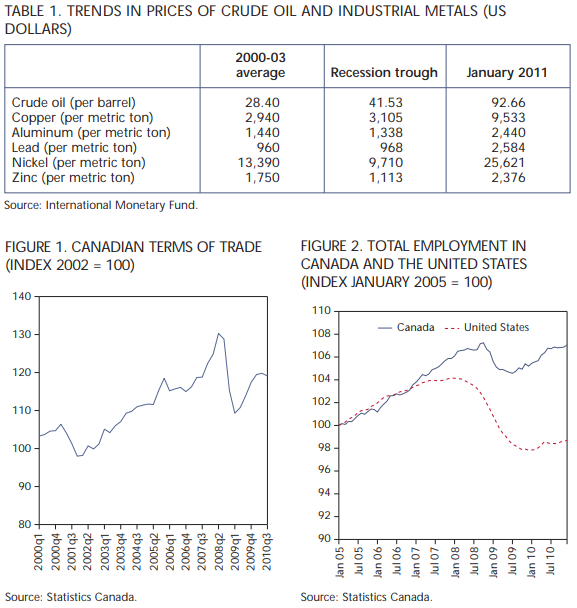

But even after the 2008 crash, the trough prices of crude oil and industrial metals were about the same as or higher than in the early 2000s, signalling a long-term upward trend (table 1). After just 18 months of tepid economic recovery in the industrialized world, commodity prices have doubled. Many of them are approaching prerecession levels and will likely accelerate further when the industrialized world’s recovery gains momentum. Far from a speculative bubble, the 2004-08 runup in commodity prices was a reflection of strong growth in resource-hungry emerging economies, which shows no sign of abating. So high commodity prices are likely to persist for the foreseeable future.

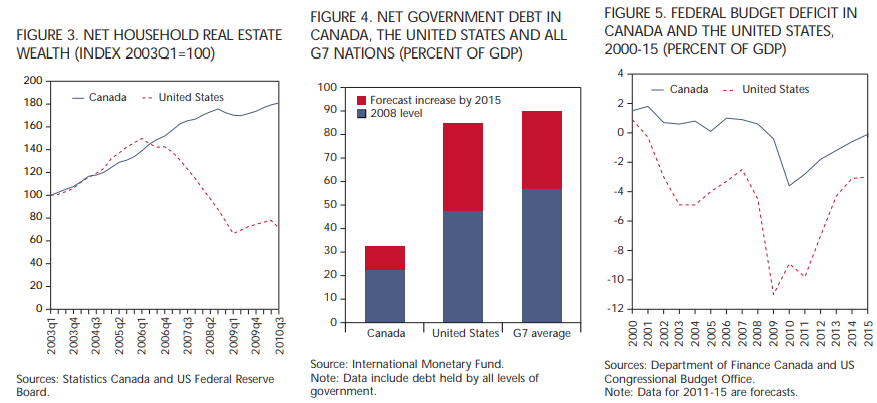

This ongoing commodities boom strengthens Canada’s economic hand, and, as I predicted in the February 2009 issue of Policy Options, kept the recession shorter and shallower here than anywhere else in the G7. As a major exporter of petroleum, natural gas and industrial metals, Canada has benefited from soaring demand and high prices, which have not only enriched the natural resource sector directly but also led to a significant increase in broader purchasing power. This improvement in the “terms of trade,” as it is known in economic parlance, transferred hundreds of billions of dollars from resource-consuming countries to Canada prior to the recession, a trend that continues today (figure 1).

Since the beginning of the recovery in June 2009, growth in real GDP — the value of what is produced in Canada — has averaged 2.8 percent annually, while growth in real national income — the purchasing power that the output generates — has averaged 4.7 percent. The difference is the “windfall” to the economy of high resource prices, and it translates into almost $30 billion to date, which has boosted domestic demand and helped shield the macroeconomy from the adverse effects that would typically result from a flagging American economy. This is one of the reasons that Canada has regained almost all net jobs lost during the recession (figure 2). Abundance of natural resources that the world wants also puts Canada in a strong bargaining position with the United States vis-à-vis privileged access, particularly to crude oil. As noted by several authors in last month’s issue of Policy Options, Canada is far and away the largest source of US imported oil (accounting for almost 15 percent of total US consumption) counting the oil sands, has the second-largest total proven reserves in the world, behind only Saudi Arabia. A similar story can be told for natural gas.

But China and other large emerging markets, most of whom have negligible reserves, will also be vying for access. This provides Canada with a unique opportunity to engage the Americans from a position of strength with regard to developing the coordination of North American fossil fuel supplies to ensure that the benefits are fairly balanced between the US desire for security of supply and the Canadian desire for a premium price for privileged access.

More importantly from the perspective of the continental balance of economic power, the top corporate tax rate was slashed from 28 percent to 21 percent, and the Conservative government continued this trend by cutting it further to 15 percent by 2012. As a result, the total corporate tax burden has gone from worst to first, with the advantage over the United States growing increasingly large.

We should also not forget the importance of hydroelectricity, for which exports from Canada are important sources of clean electricity in the US Northeast and Pacific Northwest. Here again, investments in capacity not only are in the interest of Canada’s own energy needs, they strengthen our role in continental management of energy and the environment.

A second important shift is in the comparative fiscal and financial position of the two neighbours. Sound fiscal and economic management has paid considerable dividends to Canadians. Prudent lending practices and a well-regulated (if oligopolistic) banking sector allowed Canada to avoid the worst of the housing and financial crisis that buffeted our southern neighbour.

In sharp contrast to Canada, in the US, net household real estate wealth dropped by a whopping 50 percent from 2006 to 2009 and shows no sign of recovery in the near term (figure 3). Even though Canadian households are taking on debt at rates comparable to their American counterparts, the strong labour markets and terms of trade noted earlier provide the purchasing power to make it sustainable.

Canada’s stellar fiscal record is well-known among policy wonks, but two main points merit repeating: (1) Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio, which fell throughout the 2000s until the recession hit, is orders of magnitude lower than those of other G7 nations and is projected to grow only modestly in the next five years (figure 4); and (2) the federal deficit caused by the recession and associated stimulus spending peaked at less than 4 percent of GDP and is forecast to diminish to zero by 2015 (figure 5), provided the government can deliver on pledges to cut spending. This fiscal strength allowed Canada to mitigate its recession without busting the budget, and makes the longer-term fiscal challenges more manageable.

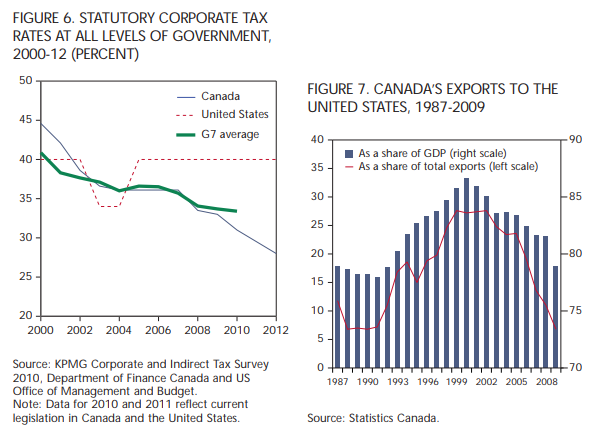

It is significant that Canada was able to maintain its fiscal strength through the 2000s even while reducing both personal and corporate income taxes. Finance Minister Paul Martin’s 2000 budget contained the biggest personal income tax cut in Canadian history — $58 billion over the subsequent five years. More importantly from the perspective of the continental balance of economic power, the top corporate tax rate was slashed from 28 percent to 21 percent, and the Conservative government continued this trend by cutting it further to 15 percent by 2012. As a result, the total corporate tax burden has gone from worst to first, with the advantage over the United States growing increasingly large (figure 6). This has had salutary effects in terms of domestic business profitability and will make Canada a more attractive destination for foreign firms. Contrary to popular (mis)perception, these corporate tax reductions had a negligible effect on the health of public finances. During the 2000-08 economic expansion, corporate tax revenues actually increased from 2.2 percent of GDP to 2.7 percent of GDP and grew by almost 70 percent in dollar terms: corporations paid lower tax rates, but earned much higher profits. One might have expected the United States, which did not cut corporate taxes, to see a significantly better fiscal outcome, but trends were almost identical: corporate tax revenues increased from 2.1 percent of GDP to 2.7 percent of GDP, and revenues grew by about 75 percent in dollar terms.

This Canadian fiscal and financial exceptionalism is now beginning to pay dividends with regard to Canada’s influence in global economic affairs. The G20, a Canadian creation, was pivotal in providing a coordinated fiscal policy response to the global recession. Canadians hold prominent positions in the Financial Stability Board and other international groups seeking to avoid future financial crises. And numerous countries have looked to Canada for lessons on fiscal discipline and financial prudence.

Turning to trade, because of history and geography, the United States will always be an important market for Canadian exporters. But here again, there is a fundamental shift under way that militates for diversification of Canadian trade flows. Some diversification away from the United States is already happening due to market forces (figure 7). The increase in demand for crude oil and metal has caused exports to nonindustrialized markets to grow rapidly, mostly due to demand for natural resources.

While acknowledging that the Canada-US trade relationship will always be an important one, Canada would be wise to be more proactive with regard to the trade diversification that is already beginning to take place by focusing strategic attention on Asia. While China is one obvious target, much research points out that the benefits of engaging India would in fact be greater — it has a younger population whose purchasing power is destined to grow dramatically.

Furthermore, its link to Canada via membership in the Commonwealth as well as the large Indian diaspora in Canada means that the cultural and historical links that are so important to building a mutually beneficial trading relationship are already largely in place.

Building trade links to pave the way for formal agreements takes time and effort, and the recently announced intention of beginning negotiations for an eventual trade agreement with India is a sign that the federal government understands the strategic value of looking outside North America for additional export markets. Another avenue is the TransPacific Partnership, a multilateral free trade agreement that currently has four members (New Zealand, Singapore, Brunei and Chile). Australia and the United States are among a half-dozen other countries currently negotiating membership, but Canada has so far not committed to joining, nor have we even been invited to do so. By sitting on the sidelines, we are missing an opportunity to get in on the ground floor with respect to nascent Asian economic integration, and we do so at our peril. At the same time, with the US domestic economy hamstrung by the impact of the financial crisis on consumer purchasing power, the trade aspect of continental relations has come back on the American radar screen after having been shoved aside in the wake of post-9/11 security concerns. President Obama’s vow to double exports in the next five years, articulated in his most recent State of the Union address, was not the headline promise, but it holds particular importance for Canada, because we are the top destination for American exports — 20 percent in 2010, far ahead of Mexico’s 13 percent. The thickening border affects goods moving in both directions, and Americans are beginning to realize that economic costs of border security are not negligible. The recent rejuvenation of talks to develop a continental “perimeter” with the goal of reducing the burden of crossing the border is undoubtedly motivated in part by the desire (and need) for the United States to facilitate trade flows north of the border. That this happened at the top, with Prime Minister Harper and President Obama personally signing off on the “Beyond the Border” declaration after their White House meeting last month, means the process has been engaged from the top, and central agencies on both sides of the border, notably the Privy Council in Ottawa and the National Security Agency in Ottawa, will follow up.

This, combined with the strong Canadian economy, gives Ottawa a stronger bargaining position than it has had in quite a long time and should ensure that whatever agreement is hammered out is fair and beneficial to both sides.

In short, the stars are aligned for a bright economic future for Canada, due to both the good fortune of being endowed with natural resources that the world needs and the good management of its fiscal and financial affairs.

The result is that Canada’s economic destiny, while inevitably affected by the health of the American economy, is no longer dependent on it. This seemingly subtle distinction makes all the difference with regard to Canada-US economic relations, and Canada should not be afraid to use its newfound strength to take its well-earned place as a full partner in continental (and, for that matter, global) economic affairs.

Photo: Shutterstock