Once recreational cannabis becomes legal in Canada, the central question is whether the provincial retail markets will succeed in competing with the black market. Provinces with more emphasis on private retail models will likely succeed better than provincial governments insisting on uniquely running their own stores. This is because private retailers have an incentive to be profitable and efficient. However, different versions of private sector involvement will lead to different outcomes.

There is considerable variation in retail systems across provinces. Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island have decided to sell cannabis through government-owned stores, as is the case with liquor in these provinces. Alberta has opted for a purely private sector retail distribution channel. British Columbia has chosen a hybrid public-private system, offering cannabis through some government-owned stores, but allowing the private sector to take a lead. On the other hand, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan have decided to allow private retail sales with liquor control authorities responsible for regulating private stores. With the exception of Manitoba, all provinces have decided to directly run online sales.

Until recently, Ontario had planned to set up a separate Crown corporation, which would be responsible for wholesale purchases and retail distribution. However, the new Conservative government has abandoned that approach and instead decided to allow cannabis sales through privately owned stores, as in Alberta. On this score, Ontario’s new Premier appears have the right instincts in moving away from a government-run retail model. However, only online sales will initially be available. Private retail cannabis stores in Ontario are set to open on April 1, 2019.

It is also important to acknowledge interprovincial differences, even with similar looking distribution structures, as they have the potential to impact consumer experience. For example, while cannabis stores in Nova Scotia will be government-run, the province will sell cannabis and alcohol together from the same outlets. In contrast, Quebec, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island have chosen to establish stand-alone cannabis stores that are separate from outlets selling alcohol. Another key difference is with respect to selected retailers in provinces opting for a private system. For example, Saskatchewan and Alberta have chosen a collection of small and large companies to run retail shops, as both Canopy Growth and smaller players have won retail licences in these provinces. On the other hand, a majority of retail licences in Newfoundland and Labrador have gone to large players like Loblaws.

Government distribution systems have several inherent flaws, chiefly stemming from the fact that they are a monopoly…there is no incentive to compete on prices, be efficient and ensure that they are well stocked with products to accommodate a diverse array of consumer tastes.

Of course, there is nothing intrinsically wrong in having different retail distribution systems across provinces. It might be efficient as governments are able to tailor structures specifically to local needs. However, government distribution systems have several inherent flaws, chiefly stemming from the fact that they are a monopoly. With the absence of competitive pressures, there is no incentive to compete on prices, be efficient and, most important from the perspective of marijuana products, ensure that they are well stocked with products to accommodate a diverse array of consumer tastes. This is critical given the wide variety of edibles and cannabis-infused products, which consumers may prefer and wish to try out. If a sufficient diversity of products is not available, then consumers clearly have an incentive to go to the black market.

But the private/public model is not the only critical component of whether a legal marketplace will successfully compete with the illegal one. Another legitimate concern would be whether the chosen mode of retail distribution results in an insufficient number of stores, inconveniencing consumers and consequently facilitating the existence of widespread black markets.

In this respect, Quebec’s plan to have only 20 government-owned retail stores during the first year of legalization is of significant concern. This is woefully inadequate and, on a per capita basis, very much behind the smaller Atlantic provinces. Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island will have 24, 20, 12 and 4 retail locations, respectively. While British Columbia and Alberta have not released details on the number of licensed retail stores, Saskatchewan has released 51 retail permits and Alberta has indicated that it will allow up to 250 stores.

Ontario had originally committed to 30 to 40 government-owned stores. However, with distribution now in the hands of the private sector, the province has yet to announce the total number of retail licences that will be available for distribution. Here’s a look at the number of proposed retail stores per 100,000 of population, per province.

Even excluding Alberta, Quebec is significantly behind the other provinces. On a per capita basis, the proposed numbers of stores in Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan are more than 16 times what has been proposed in Quebec. The per capita number of stores in Nova Scotia is almost 8.6 times that in Quebec.

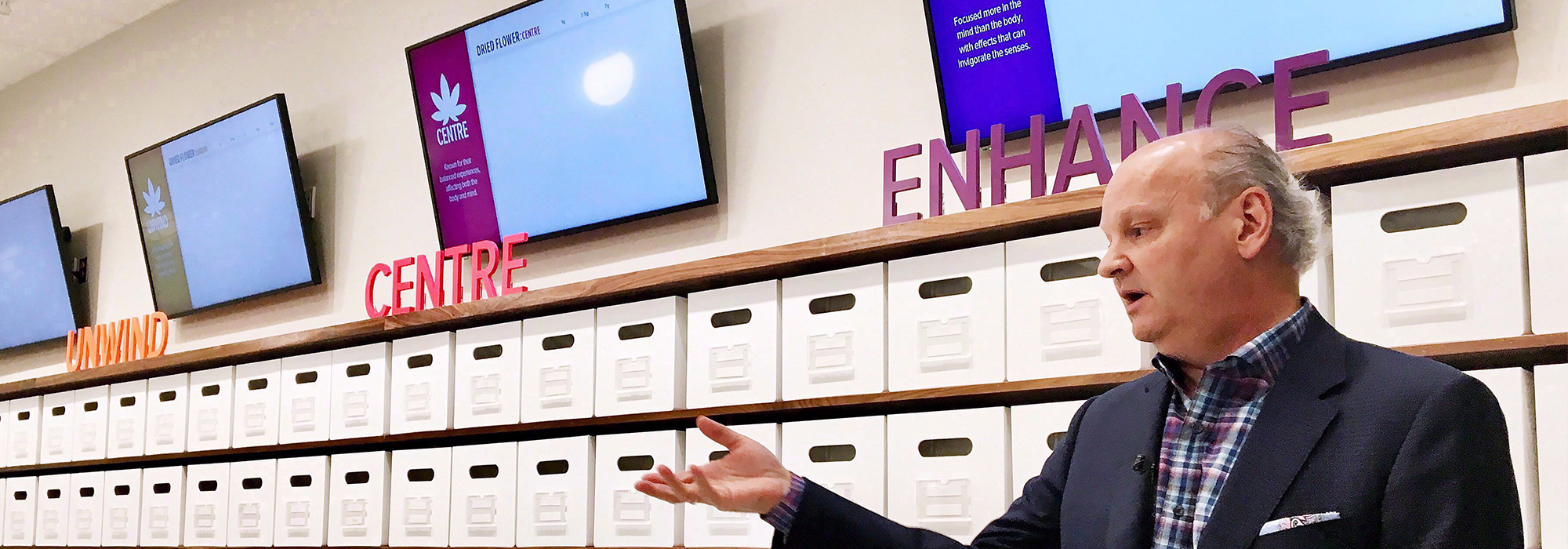

Finally, another element to consider in the competition with the illegal market is consumer retail experience from legal stores. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia have revealed the designs of their cannabis stores, which display foresight and innovative thinking. The interiors are not spartan, and are in fact welcoming, while ensuring that products cannot be accessed by the public, and entry by anyone under the legal age is not possible. From a public health perspective, there may be concerns that having sleek, modern cannabis stores will invite significant consumption of the product. However, this is precisely what is needed to ensure that most people do not go to the black market. Retail outlets should be designed so that consumers do not feel stigmatized.

There is no need to have provincial governments involved in setting up and running retail cannabis stores. Retail distribution should be left in the hands of the private sector, with appropriate regulations to ensure quality and protection for minors. The market can efficiently determine store location, with competition resulting in lower prices, cost efficiencies and a diverse variety of products, all of which are critical in eliminating the black market.

Quebec needs to play serious catch-up and consider participation from the private sector. If it doesn’t, the result will be a flourishing black market. In this respect, it is important to acknowledge that, while Ontario made the right decision to move to private retail stores, its decision to have retail stores only from April 1, 2019, may prove to be a costly mistake. If customers are not satisfied with online services, whether in terms of product variety or delivery time, they will have an incentive to try the black market. There is no reason why Ontario cannot grant licences to enable some private retail stores to operate long before April of next year.

In a few years, there will be sufficient data to assess the pros and cons of each different retail distribution system. However, provinces that have chosen a more deregulated approach with sufficient retail access should see a dramatic reduction in black market activity as well as see less government money being soaked up in a market that should be run primarily by the private sector.

This article is part of The Economics of Canadian Cannabis special feature.

Photo: Nova Scotia Liquor Corporation president and CEO Bret Mitchell gestures during a media tour of a cannabis section at one of its stores in Halifax on July 18, 2018. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Aly Thomson

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.