“We do not have to worry about Canada, we do not even think of them.”

So said Donald J. Trump to Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto during a phone call on January 27 of this year, according to transcripts obtained by the Washington Post. And while this writer cannot begin to fathom what’s going on in the head of the 45th president of the United States vis-à-vis bilateral relations with Canada, two things have been made clear by the fullness of time.

First, Trump’s statements have changed. Not only did he tell American farmers in April that “People don’t realize Canada’s been very rough on the United States. I love Canada. But they’ve outsmarted our politicians for many years,” in reference to the softwood lumber file, but he also said, “Canada, what they’ve done to our dairy workers, it’s a disgrace.”

Second, regardless of whatever Trump may be thinking, Canada is certainly front and centre in the minds of the US negotiating team appointed to face off against their northern counterparts for the first round of NAFTA talks that begin on August 16.

Led by US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, the Americans released their negotiating objectives last month, and they left little room for ambiguity. The objectives state that eliminating “non-tariff barriers to U.S. agricultural imports” is an official priority when renegotiations get underway in Washington, DC. There is no doubt: Canada’s supply management system is in the US’s crosshairs.

But when Canada’s negotiating team sits down to discuss the future of the continental trade deal, it will do so representing a domestic population with conflicting mindsets on supply management.

Results from our self-commissioned and self-funded Angus Reid Institute survey of Canadians this summer reveal two attitudes: Canadians as consumers, the majority of whom prefer free-market pricing and more access to foreign products; and Canadians as citizens, who lack consensus on the policy itself, but express concern for domestic farmers. The survey questionnaire asked respondents about the basics of how supply management works, what products it controls, and the main arguments for and against the policy.

The population does have one thing in common. Most are largely unaware of the detailed components of supply management. Just 4 percent say they know “a lot” about the policy, while 58 percent say they know nothing about it at all. Most are unable to accurately choose which products are regulated under the system — and even among those who say they know a lot about it, one in three say beef and pork are included; they aren’t.

Canadians as consumers

As consumers, Canadians face higher prices than Americans for some supply-managed goods. Quotas on production and substantial levies on imports have helped create that reality. Recent data suggest that the average milk price in Canada is almost two times higher than in the United States, while a chicken breast in Canada costs about 15 percent more than its American counterpart.

Most Canadians say they would give up farmer security for lower prices. Presented with the current market prices in Canada for eggs, chicken, milk and cheese, and other items (as compared with what research suggests the cost might be without supply management), just one in three say they prefer to pay the current rate, in order to uphold supply management and the security it brings.

Even among those who say they support supply management, 33 percent say they would choose the cheaper price if it were available.

While many proponents of the current system say it sustains the quality of products because farmers’ profits are stabilized by management, there’s little consensus about what might happen to products if the domestic market were opened up to more international competition. An almost equal numbers — just over one in three in each camp – agree (35 percent) and disagree (38 percent) that quality will suffer. The rest are uncertain (27 percent).

The more appealing argument seems to be access to more choice. More than half (56 percent) say Canadians will benefit from more choice at the grocery store if supply management is ended.

Canadians as citizens

When supply management was first introduced in the 1970s, the impetus for the policy was to protect small family farms, guaranteeing farmers a fair return for their hard work. Between 1971 and 2011, however, the number of dairy producers in Canada has dropped 91 percent, causing some to question the system’s relevance.

Indeed, just 29 percent of Canadians say they are concerned that farmers won’t survive in a free market. A greater number, almost four in ten (39 percent) don’t share this concern, while one-third say they aren’t sure how the changes would play out.

As citizens, many Canadians show compassion for farmers. If the system was ended, pluralities voice support for compensation mechanisms that would allow agricultural producers to recover the lost value of their quotas.

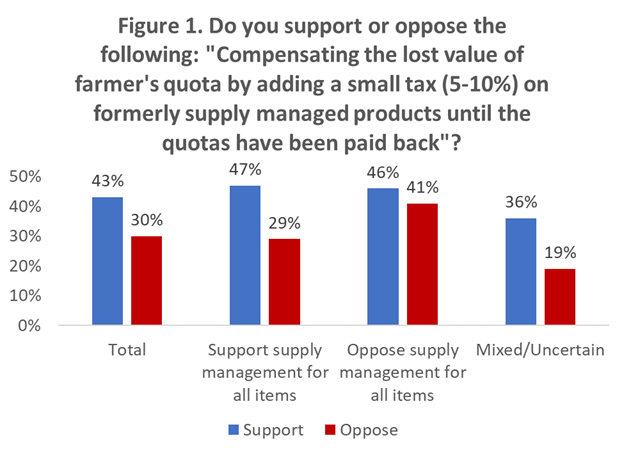

When Australia’s dairy industry reformed its managed system, the government there employed an 11-cent-per-litre tax on milk. Four in ten Canadians (43 percent) say they support a 5 to 10 percent tax on goods that would no longer be supply managed, if it were necessary to help farmers transition. Even among those who say they oppose supply management, 46 percent support such compensation (figure 1).

Supply management meets trade talks

Opinion on support for and opposition to elements of supply management is somewhat nebulous unless it is gauged within the current context of NAFTA talks.

Until now, the federal government has maintained a firm commitment to upholding the supply management policy. Prime Minister Trudeau has noted that significant trade deals have been signed while protecting the system, and said in July,“We are going to continue to do that.”

Should elbows become especially pointy and table-banging become thunderous during renegotiations, however, it would appear that more Canadians are willing at least to put supply management on the table rather than die on that hill.

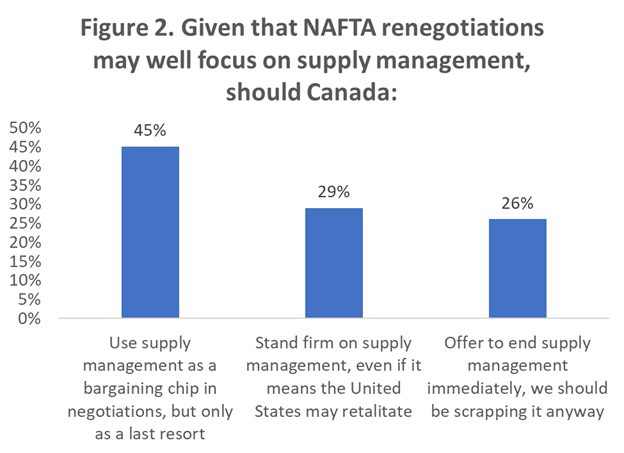

Nearly equal numbers say the system should be either scrapped outright (26 percent) or protected at all costs (29 percent), while the largest group — close to half (45 percent) — would be satisfied with using it as a bargaining chip (but only as a last resort), knowing that the US is keen to dismantle the system and that several other issues are on the table (figure 2).

Would Canada give up some of its agricultural market protection in exchange for a better softwood lumber deal? What about independent dispute resolution, particularly chapter 19? President Trump would like to nix the mechanism entirely, while Canada and Mexico both reject that proposal.

Then there are Mexico’s objectives, which few are talking about now, but which won’t be ignored once trilateral talks begin. Should this triple-threat wrestling match get bloody, our public opinion polling suggests that Canadians may be convinced to either uphold or concede supply management during negotiations. Ultimately, it will be up to Canada’s negotiating team to decide how much is too much to give.

This article is part of the Trade Policy for Uncertain Times special feature.

Photo: Dairy cows are shown in a barn on a farm in Eastern Ontario on Wednesday, April 19, 2017. The U.S. dairy industry has submitted its demands for the renegotiation of NAFTA, pushing for freer trade in dairy overall and more specifically for a reversal of new Canadian rules on milk-derived products. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.