Nearly 25 years ago, former prime minister Brian Mulroney was headed to work, sitting in the back of his limousine as it headed down Sussex Drive. As the car passed the Royal Canadian Mint, Mulroney gazed out the window and was startled to discover construction workers busily dismantling the magnificent stone architecture of the 1908 building.

“Stop the car,” Mulroney told his driver. The prime minister got out and asked the workers just what they thought they were doing. The men explained they had been sent by Public Works.

Mulroney bluntly gave them a new work order: “You can put your tools down, guys, because you’re not doing it.”

Several minutes later, as soon as he was in his office, Mulroney immediately phoned his public works minister, Stewart McInnes, and ordered an abrupt halt to the deconstruction of the mint.

Generally, it’s not a good idea for politicians to get mixed up with construction projects, unless of course it involves handing over a cheque at a safe, nonpartisan distance. Just this fall, controversy has erupted over whether Parliament Hill construction contracts were handed out to Conservative-friendly contractors.

But there are times when not getting involved is a scandal too — as some might argue about the current crumbling state of the historic architecture right on the very doorstep of Parliament Hill.

Former prime minister Mackenzie King, who was also a bit of an architecture buff, once lamented that Canada had too much geography and not enough history. If he were alive today, though, to see what’s happened to a street that he had a hand in designing, he might be tempted to say that the capital has too much construction and not enough respect for history.

Thanks to that massive and controversial renovation project under way on Parliament Hill, Wellington Street is also under architectural siege. Grand old buildings facing Parliament are being gutted and/or turned into cubicle space to accommodate the spillover of the construction taking place at West Block and environs. It is a seemingly endless Public Works project — yes, it’s Public Works, again — which has left Canada’s political main street virtually deserted.

As a visual metaphor, it’s powerful. Not only is Canada’s Parliament broken, but so is the immediate vicinity. One also wonders: what other national capital would tolerate such a hollowing out of the area immediately around the seat of federal power?

Back in the 1970s, when Washington recognized the crumbling state of Pennsylvania Avenue — America’s political main street — Congress created a special development corporation, to ensure that the area was maintained “in a manner suitable to its ceremonial, physical, and historic relationship to the legislative and executive branches of the Federal Government and to the governmental buildings, monuments, memorials, and parks in or adjacent to the area.” Funnily enough, Canada’s own US embassy, designed by Arthur Erickson and unveiled by Mulroney in 1989, was a major part of the rehabilitation. Back home in Ottawa, though, it may be time for Canada to give some thought to what’s happened to its own version of Pennsylvania Avenue: Wellington Street, the ghost avenue of Ottawa. Who’s stopping the car — and the construction — these days?

David Jeanes is head of Transport 2000, a transport-advocacy organization, but he is also an architectural history expert who leads Heritage Ottawa tours of various streetscapes around the capital. Jeanes offered to do a special tour for Policy Options, to reveal some of the faded glory of the street directly in front of Parliament Hill; to show what historical riches are there, underneath all the dust and desertion.

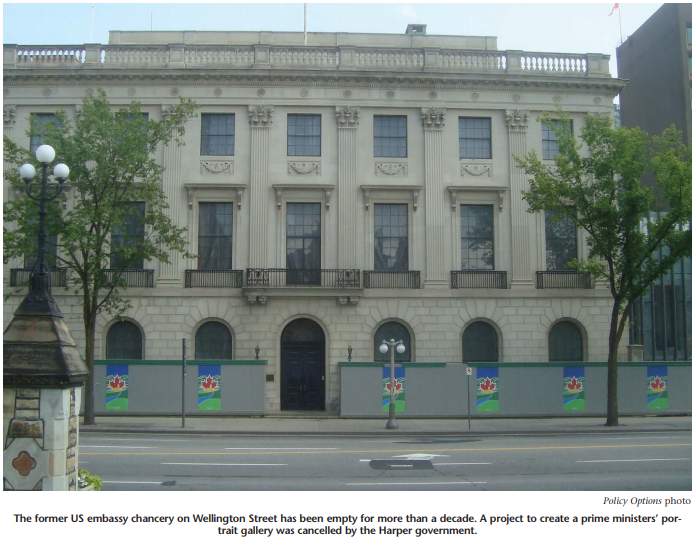

The tour starts at Metcalfe and Wellington, in the shadow of the Prime Minister’s Office at the Langevin Block, and just in front of the old US embassy. This was the building once designated to be the site of Canada’s new portrait gallery until Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government decided to nix the project.

Jeanes draws the visitor’s eye to the architectural details and then tells the story of the building. It was designed around 1930 by renowned US architect Cass Gilbert, who also was the artistic brain behind the US Supreme Court building in Washington. When Gilbert started the project on Wellington Street, Canada was still merely a dominion in the British Commonwealth, and no embassies, only consulates, stood in the capital. But privately, Mackenzie King had assured the US that by the time its building was finished, Canada would be a full-fledged nation unto itself. Sure enough, Canada received just such independence through the Statute of Westminster in 1931, and the building opened soon afterward as a full embassy.

Mackenzie King, who was also a bit of an architecture buff, once lamented that Canada had too much geography and not enough history. If he were alive today, though, to see what’s happened to a street that he had a hand in designing, he might be tempted to say that the capital has too much construction and not enough respect for history.

The inspiration behind the design of the building comes from Britain and more particularly the Banqueting House at Whitehall, designed by Inigo Jones. Jeanes isn’t sure, but he suspects this may have been a bit of a private joke by Gilbert. The Banqueting House was where Charles I was beheaded in the 17th-century struggle over the supremacy of Parliament. Right in the middle of the old US embassy building on Wellington Street, directly facing Parliament Hill, is a small balcony in the same spot where Charles I was executed outside the Banqueting House in 1649. The King lost the battle. Perhaps Gilbert was trying to make a subtle, architectural insider’s nudge about where power should lie in modern-day democracies. Jeanes likes to think so.

The inside of the building was once very grand, Jeanes says, but he worries about its current state. Since the portrait gallery was abandoned, construction and climate control inside the building have reportedly stood still, too. There’s been some talk of turning it into a “reception centre” for the prime minister to greet foreign dignitaries, but for now, all Public Works is saying is that the government is “currently developing potential options for further assessment to ensure that a best use is found for this important heritage building.”

Beside the old embassy building is an empty parking lot, where some early and mighty Canadian banks once stood. In fact, 100 years ago or so, Wellington Street was effectively an architectural monument to banking and commerce.

“This was Bankers’ Row,” Jeanes says. “At the end of the 19th century, every building on this block contained a bank. And all the banks were facing Parliament. So that was the divide between the town on the south side of Wellington, and the Crown, on the north side of Wellington.”

Onward past the parking lot sits another apparently deserted building — this one a small, narrow former home to the Union Bank of Canada.

“It was the last new building built on Bankers’ Row,” Jeanes says. “It was designed by architect Fred Alexander, who trained in the Department of Public Works. He was one of the architects who were responsible for the completion of the Library of Parliament. He designed the stone fence and the gates that go around the outside of Parliament Hill. But then he retired from Public Works and went into private practice, and this was one of his creations, to design this little sandstone bank.”

Usually, the public is moved to complain when construction is noisy. But on Wellington Street, where Public Works has laid waste to some grand old history in the capital, and left grand architectural buildings dust-covered and deserted, it’s the silence that’s remarkable.

This “little dwarf of a building” is also notable, Jeanes says, because of the olive-coloured sandstone, which was also used to construct Langevin Block and comes from the Miramichi area in New Brunswick. “It was considered to be quite the innovation at the time,” Jeanes says. “In fact, there were even testimonials published in the newspaper at the time, saying what a good stone it was.”

Beside the old Union Bank is the former site of Ashbury College, and a plaque denotes the significance, though the actual building now on the corner is from a later era. In the last several decades, this building has housed the CBC, the Canadian Press and now Senate offices, but here on this corner, a once-grand hotel stood, and the Prince of Wales was one of the first guests when he arrived in Ottawa to lay the cornerstone for the Parliament Buildings.

Crossing O’Connor Street, the walk down Wellington brings us up to the imposing and, again, empty former Bank of Montreal building, which stretches one whole block back to Sparks Street. BMO was actually the first bank to set up shop on Wellington Street, but its first few headquarters along the street were more like houses, or mansions. The grand stone building that now sits on that corner was erected in the 1930s and was intended to cast an imposing presence on the street.

Some of that grandeur will be allowed to remain in the new configuration of Wellington Street, thankfully. Public Works says the Bank of Montreal building will have a ceremonial future. “This federally classified heritage building will become the new permanent location for the Confederation Room (room 200 in the West Block),” says Lucie Brosseau, a spokesperson for Public Works. “The large, formal banking hall will provide ceremonial and reception space immediately adjacent to Parliament Hill. This project also involves a new addition, which will be constructed to the west of the existing heritage building and adjacent to the National Press Building. This project is in the design stage.”

Immediately to the west of the bank is the National Press Building, covered in scaffolding and containing only a few journalistic tenants and reminders of its old role as main headquarters for the national media. This edifice was originally known as the Norlite Building, and at the early part of the 20th century, it housed the old Department of the Interior — doling out land for national parks and the like. It’s an Italian Renaissance building whose true beauty is only really appreciated at some distance — a journalistic distance, perhaps. Atop the building are two small towers — an architectural feature known as “donkey’s ears,” which probably would delight critics of the media. Through much of the 1970s and 1980s, this building was the hub for major media outlets, and the National Press Club was its storied tenant. Sadly, the CBC, CTV and Global TV have long since abandoned the premises, and though the National Press Theatre remains on the first floor, much of the rest of the building is being claimed by Public Works for office space and cubicles. Fans of the old Press Club would weep to see the grey office dividers and cubicles in the space where flacks and hacks used to drink and carouse. Its future is murky. Public Works insists it has no further plans to change the “mixed use” of the building.

Beside the National Press Building is a gleaming white stone building that used to house the offices of the official leader of the opposition, but before that, the old Metropolitan Life insurance company. This, too, was a monument to finance when it was built in the 1920s — one of the architects was D. Everett Waid, an American who also designed the impressive MetLife building in New York during the days when there was competition to build the biggest skyscaper. Inside the front lobby of the building is a huge, colourful and gorgeous series of mosaics, depicting the insurance industry — not normally associated with opulence and colour. The mosaic shimmers with gold and is a monument to stability; one of its depictions features a contented-looking man and woman, sheltered under protective Greek pillars. The surrounding foyer is built with travertine marble, imported at great cost from Italy.

The MetLife building stands vacant at present. To see the mosaic, one has to rub the dust off the door and peer in the window and upward. “This building has been fully vacated and phase one (interior demolition, abatement and seismic reinforcement) construction began in spring 2010,” says Brosseau. “This heritage building will be fully rehabilitated and used for interim parliamentary accommodations (69 parliamentary offices and 10 committee rooms) throughout the rehabilitation process on Parliament Hill. These facilities are needed to accommodate committee rooms and parliamentarians who will be displaced from the East Block and then the Centre Block so that they can undergo major rehabilitation work.”

Jeanes’ tour has now spanned the entire length of Parliament Hill proper, and most of the sites along two large city blocks facing the Hill are scenes of construction or desertion. The odd few tourists can be seen wandering down the street, and the occasional bus tour winds noisily down Wellington, but no one is flocking to see the rich history of the buildings on the south side of the street.

We are now at the corner of Bank Street and Wellington, where the huge Confederation Building stands, intentionally designed as an architectural bookend to the Château Laurier at the other end of Wellington Street. Jeanes points out how many of the roofs on Wellington Street are green copper; this was a particular preference of Mackenzie King — evidently, from his diaries, a bit of an armchair architect.

Today, if the current prime minister has any strong feelings about the history and architecture around Parliament Hill, he has yet to demonstrate them.

At the end of the tour, Jeanes looks down the expanse of the street and politely laments that Public Works seems to have so little to do with history. Judging from Wellington Street, the mandate of the department seems to be focused more on works, less on the “public” part.

“Their mission is to provide office space to the parliamentary precinct, and that’s where it ends,” he says. “They’re the Department of Public Works, but really, they’re the department of government works. I think that’s a great pity, because these buildings could really have wonderful public roles.”

Usually, the public is moved to complain when construction is noisy. But on Wellington Street, where Public Works has laid waste to some grand old history in the capital, and left grand architectural buildings dust-covered and deserted, it’s the silence that’s remarkable.

Photo: Shutterstock