A doctor in Health. A soldier in Defence. A businessman in Finance. A scientist in Science. Much has been made of the diversity and gender parity of Justin Trudeau’s Cabinet. Yet, it is his ministers’ subject-matter expertise that may ultimately represent a more substantial development in the way Canadian Cabinets are made.

In our Westminster model of responsible government, the Sovereign (through her Canadian representative, the Governor General) exercises executive power on the advice of her Prime Minister, who holds office only as long as he or she commands the confidence of the elected House of Commons. One of the things the Governor General does on the Prime Minister’s advice is appoint the Ministry – that is, the Cabinet. Hence last week’s swearing-in ceremony at Rideau Hall, the Governor General’s official residence in Ottawa.

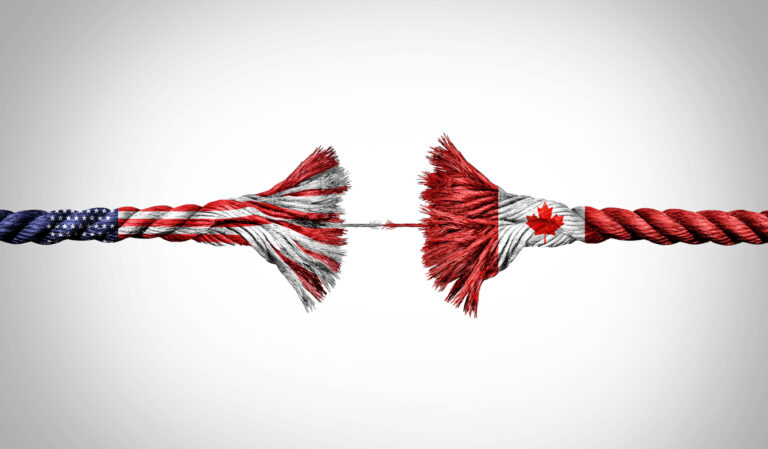

Our system of government thus vests discretion about who serves in the Ministry in two sets of hands: the Prime Minister’s and the voters’. Unlike in the United States, where there is a strict separation of powers between the legislative and executive branches of government, in Canada those two branches are fused. Since the Prime Minister typically chooses his or her Cabinet from among his or her party’s parliamentary caucus, his or her choice is more constrained than the U.S. President’s; the first criterion for appointment is usually having been elected to the House of Commons. (Prime Ministers may also name Senators or not-yet-Parliamentarians to Cabinet posts, but such appointments are rare.)

The consequence is that Canadian Cabinet ministers have rarely been subject-matter experts. Prime Ministers select and replace them on the basis of the government’s political calculations, not a particular minister’s personal expertise.

There are exceptions, of course. The Attorney General is nearly always a lawyer, since he or she serves not only as Minister of Justice but also as the legal advisor to the Cabinet. Lester Pearson served with distinction in the diplomatic corps before Louis St-Laurent named him Foreign Minister in 1948. Still, for the most part, professional experience has not been considered an especially pertinent consideration in Cabinet selection, much less an indispensable asset to a potential minister.

That’s because the skills required to provide political direction to a department or agency and to answer for it in Parliament don’t necessarily follow from the experience of having worked in a related field. Being Health Minister doesn’t have much in common with practicing medicine.

Such experience can actually be a disadvantage when it is perceived to signal a preference for one group of stakeholders or another. What happens when the Health Minister, a doctor, has to navigate disagreements between her fellow physicians and others in the healthcare system? Will the Science Minister, a scientist, be able to fund research in her own field without being accused of favouritism?

None of this is inherently problematic. It is, however, different. Non-expert ministers have historically been a corollary not merely of our form of responsible government – which requires Cabinet members to be politicians first and last – but also of our Westminster/Whitehall tradition of maintaining a permanent, non-partisan public service. Ministers are supposed to communicate the government’s priorities to their departmental officials, not necessarily to determine precisely how to implement them. If ministers are appointed for their expertise, and both expect and are expected to act accordingly, then the line between political decision-making and policy implementation may become more difficult to draw. What is traditionally kept out of partisan hands may be more likely to fall into them.

Which brings us back to the United States. When a new U.S. administration takes office, it sets about appointing thousands of officials throughout the federal bureaucracy. Entire government departments – not just their political leaders and their staff – change their complexion from red to blue and back.

Supporters of the U.S. model point to the leeway that American governments have to recruit “the best and brightest” from outside the civil service to fill senior positions. In Canada, those jobs go to career bureaucrats. The result: American officials often reach the senior ranks because of their subject-matter expertise – and their party-political connections – while their Canadian counterparts are rewarded primarily for their expert knowledge of government itself. That’s why Canadian ministers and deputy ministers, unlike the U.S. Cabinet, can be “shuffled”; if you’re qualified for one senior position in the Government of Canada, the traditional thinking goes, then you’re qualified for them all.

Yet, our new Prime Minister appears to view portfolio-pertinent experience as at least a relevant consideration in appointing Cabinet members. That’s a change, one that could herald an almost-American conception of what it means to work in the highest reaches of our government. After all, if previous professional experience should indeed inform the Prime Minister’s Cabinet choices, then why shouldn’t it also be the basis for, say, recruiting deputy ministers and other senior officials from outside the federal public service?

Start with the proposition, now evidently accepted in the Prime Minister’s Office, that a minister’s non-political expertise will be valuable in his or her job in Cabinet. If that’s true, then presumably that minister’s mandate will extend beyond what would have been expected of a non-expert with the same title. At the very least, the new minister will be expected to be more personally effective – and thus less reliant on his or her officials – than he or she might be otherwise.

It follows that appointing ministers at least in part on the basis of their professional credentials will mean that those ministers will either do more or need less. In either case, the result will be an expanded role for political appointees – namely, the Minister and his or her staff – in processes traditionally reserved to the professional public service.

So, if we view ministerial expertise, influenced as it may be by partisanship, as a potential asset in making and implementing sound public policy, then is it really such a leap to suggest that we might tolerate the appointment of subject-matter experts with the right political connections to other senior roles? We’d expand the pool of talent available to fill positions in government, and we wouldn’t even come close to emulating the U.S. model in its entirety. Should an accomplished Canadian who isn’t prepared to be a career civil servant really have to win a seat in Parliament before our government can benefit from his or her experience?

Defenders of the status quo will bristle at the mere suggestion of appointing partisans – be sure to sneer when you say it – to senior roles in government outside of ministers’ offices. There certainly are good reasons to resist reform. Canadian governments more easily build and benefit from institutional memory than U.S. administrations do, and all the expertise and professional experience in the world can’t replace a deep understanding of how to navigate bureaucratic processes and roll out a government’s priorities across dozens of departments and agencies. There may also be some areas of public policy that we should want to keep out of political hands – though the extent to which we actually do so now is hardly clear.

In selecting certain Cabinet members for their subject-matter expertise, however, Mr. Trudeau has opened the door to a broader discussion about how senior positions in our government are filled. At this point, all he’s done is signalled a subtle shift in the way ministers are made; his choices may yet only reflect a desire to show off the depth and breadth of his Liberal team. But they might also represent the beginning of a change in how we staff the senior ranks.

That’s a conversation conversation that many in Ottawa would prefer not to have, but perhaps its time has come. After all, it’s 2015.