Some of the questions I raised about the NDP numbers don’t need to be raised with the LPC. For example, it’s clear that the party used the more subdued and recent PBO fiscal projections rather than Budget 2015. More than that, the Liberals have laid bare their basis for the overall fiscal projections they provide and in many spots have even made clear the underlying data sources (CANSIM table numbers – nerd-alert! but in a good way). Likewise, the Liberals don’t seem to have dropped any of the early dollars committed on showcase policies as the NDP appear to have done with nearly $300 million from their centerpiece daycare plan.

But I think at least 2 of my previous questions apply, broadly, to the LPC numbers as well:

- When is a contingency fund political jiggery-pokery and when do we need one? From what I can tell, when Joe Oliver released his 2015 budget, the Liberals did not go as far as the NDP in reacting to the $1 billion cut in the contingency fund. But the Liberals did say the CPCs had done « everything » possible just to show a balanced budget in an election year. In their costing document, the LPC have done away with any contingency at all until 2019-20. This may be just fine but it’s worth understanding the assumptions behind this choice and that’s one area where the LPC document was quiet.

- How much more tax can CRA reasonably collect? The Liberals have, in my view, done the right thing in highlighting the role of tax expenditures in overall federal spending. The NDP made a fairly general promise to close loopholes and improve tax integrity as a revenue generator. The Liberals have said, as part of a broader spending review, they’re going to target tax expenditures that are more likely to be used by tax filers with $200,000 or more in income. I’ve written elsewhere about distributional inequities in some recent boutique credits. However, to get the tax simplification and improved revenues, we shouldn’t exclude the boutique credits used by the already comfortable, not just the rich – even if that makes for a harder sell in an election — and we should consider policy criteria in addition to equity (like efficiency and transparency).

Also, I think all promises on « tax integrity » should come with a great big asterisk: non-compliance comes from both deliberate and involuntary (accidental or mistaken) taxpayer actions and the causal links between government action and compliance outcomes are still being figured out (see for example this from the OECD in 2014).

I have a few additional questions that are unique to the LPC’s numbers. Here they are, in no particular order of importance:

1) Does the $5 million / year booked for the cost of making the Home Buyer’s Plan (HBP) more flexible include tax revenues when borrowers fail to repay? Only 20% of Canadians say they’ve used the HBP to take money out of their RRSP (Survey of Financial Security, 2012) so this policy change might boost that percentage a little (I’m not totally convinced that’s a good thing). But a little more than 1 in 3 of those HBP users will miss their annual RRSP repayment and have to pay income tax on that part of their withdrawal. If what we really want is to make RRSPs a more flexible ‘lifelong savings’ account, then there are a pile of other changes we should be making instead of piecemeal ones.

2) If the new boutique credit for teaching supplies proves to be inefficient or inequitable, would an LPC government be willing to see it chopped as part of the planned spending review?

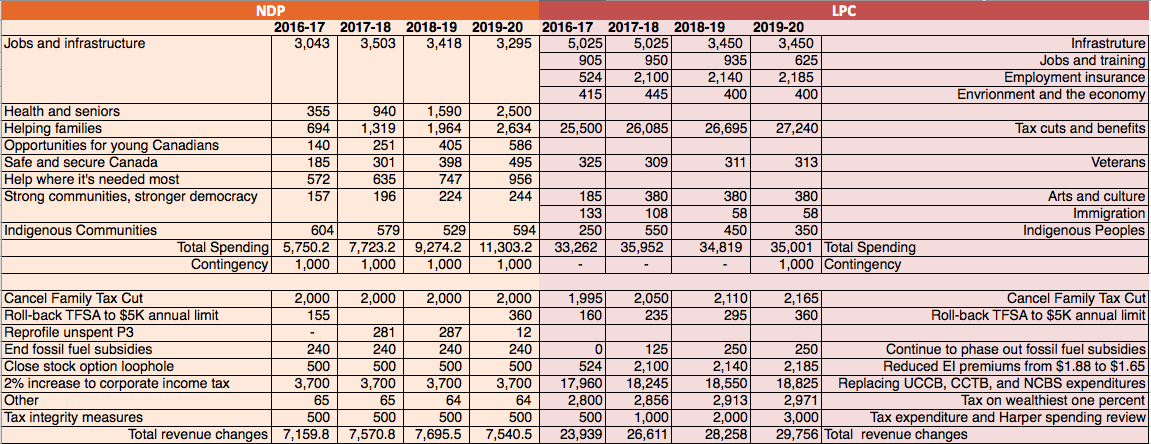

3) What does « properly funded » to do platform costing mean for the PBO? Let me be clear – I’m keen on having shared, neutral and expert review of party platform costing. I mentioned that in my last blog and Stephen Tapp wrote a thoughtful and important response on the problems of arbitrary baselines, risks of politicization and the inevitable messiness that make cross-platform comparisons hard, if not impossible. [I’ve tried to line up the NDP and LPC spending and revenue promises in a single table – see below – and that was hard enough!]. The 2 international examples cited in the LPC costing document (Australia and the Netherlands) have far greater resources than our current PBO but those 2 models also have serious downsides, at least from what I can see.

In the Land Down Under, parties can submit requests for costing to the PBO and different rules govern how the PBO publishes the results, depending on whether an election has already been called or not. Outside of the election period, it looks like the PBO in Oz will do something very similar to ours here in that it will make its analysis public when the work is done. In that case, platform development teams would have little to no incentive to use the PBO lest they tip their hands on their planned platform without a nice launch event. Aussie parties can also submit lists of election platform promises during the election period, but as far as I can tell, the PBO only releases their costing estimates 30 days AFTER the election day (and only gives parties their own costing information 48 hours before the post-election report). So the Australian model may not do much to help voters sift and sort between competing proposals before they cast their ballot.

The Dutch model is definitely geared towards making information available before election day but wow does it demand forward planning by all involved! The common fiscal projections are done a year out from the election, the manifestos are set 6 months out and the CPB (the Dutch PBO equivalent) has 3 months to then cost the platforms — and that’s with a serious staff contingent. There are always real trade-offs among timeliness, responsiveness, transparency and capacity, just as with all neutral civil service offices. This doesn’t mean that our PBO shouldn’t take on platform scrutiny but it does mean we should give thought to the process and properly resource capacity so it is used and useful to the public.

The devil is always in the details for ANY platform promise. In their favour, the Liberals have made many more of their platform details explicit and that’s an important feature we should expect of all parties.

Disclosure: I did give the LPC technical input on a few topics as they developed their platform. Another party also contacted me for informal technical background. I was not involved in the work to cost the platform of any party. You can read my longer disclosure statement here.

Photo: by Justin Trudeau / All rights reserved