Much of labour economics used to be framed by a traditional male breadwinner model – Dad works full time, Mom stays at home and only works for pay when the family needs the extra money. We all know such models of work and family are increasingly irrelevant, but I see it creep back into our work too often. Yes, this often annoys me.

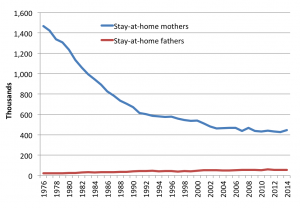

To make the irrelevance of traditional models clearer, a report prepared by Sharanjit Uppal from Statistics Canada last week demonstrated the clear shift away from single earner households, particularly those where mom stays at home full time. Reproduced below, we see fewer at-home-moms every year and any increase in the number of at-home-dads is insignificant in comparison. Overall, 52% of couples with kids had mom staying at home in 1976. By 2014, that’s down to only 16.2% of couples with kids. By 2014, only 2% of couples with kids had dad at home, up from less than 1% in 1976. Simply put, the way in which we organize our families and work lives has changed dramatically in the past four decades.

Despite these trends, I continue seeing examples of how we derive and frame our labour market statistics in ways that rely on the male breadwinner model.

Recent discussions of pension coverage are a great example.

In some work I did with Kevin Milligan on CPP reform, we pointed to some great work by Ostrovsky and Schellenberg at Statistics Canada who show that it’s the middle-income households where neither spouse has an employment-based pension that tends to have low income replacement rates in retirement. Note the importance of ”œeither spouse” having a pension.

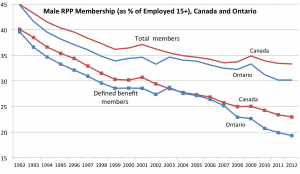

But then when I hear people discuss concerns about pension coverage, they usually start with this graph:

Among employed men in Canada, fewer are members of a registered pension plans and most of the decline represents a decline in defined benefit pensions (those wonderful pensions that guarantee a fixed benefit for the rest of your life). This is often all that is presented to justify immediate policy reaction.

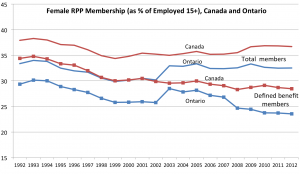

But then I also show the information for employed women:

Pension coverage among employed women hasn’t decreased in the past couple decades, though there has been some decline in defined benefit coverage. When you combine this with the fact that more women are working, there’s actually an increase in the total portion of women (employed or not) that have pension coverage.

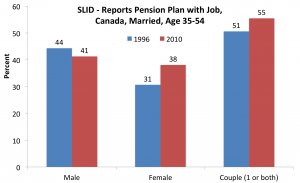

So that brings us back to what is going on within a household. In the following, I tabulated pension coverage among married individuals and couples aged 35-54. Unfortunately, using the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics I can only see whether someone reports coverage by a pension plan at their main job – and you’d be surprised how many people get that wrong – but at least it’s a good indicator for trends.

There appears to be an increase in the portion of married couples that have pension coverage! There’s an increase in the portion of women with pension coverage! Why are we so stuck on the fact that men’s coverage has decreased?

To be clear – because I know there’s a bunch of people ready to take that last graph and claim there’s no need to worry about retirement income – there remains a large portion of families with no pension coverage. That’s a concern.

Back to the bigger picture.

The fact that our workforce and how we organize our households has changed so much over the past four decades needs to be incorporated into our interpretation of all labour market statistics.

Consider recent discussions of non-standard employment. Yes, many part time casual jobs represent really crappy work situations that we need to pay attention to. However, we need to keep in mind that many people (especially parents of school-age kids) enjoy having flexible work arrangements or work part-time so they can balance work and family better. Consider that many dads might be cutting back on work hours to join moms as primary caregivers of their children. Consider that many short-term contracts are in place because employers have an obligation to offer job protection for employees away on maternity and parental leave. These aren’t bad things in my view and I suspect most people wanting to defend folks in crappy jobs would agree.

Our challenge then is to prepare and present better statistics and be more critical with their interpretation when trying to develop policy. It’s easy to look at trends for men in the labour market and interpret them in isolation, I admit I’m often guilty of doing so. But we need to think about labour supply at a household level.

Note: Some of the graphs presented above were part of a presentation at the Queen’s International Institute for Social Policy. CANSIM 280-0009 has RPP numbers.