Earlier this month came big news about the Canada Learning Bond (CLB): following the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s landmark report, the National Association of Friendship Centres (NAFC) along with a coalition of foundations, banks and post secondary institutions announced they would coordinate their efforts to promote enrolment in the CLB among aboriginal and first nations families.

This is as close as you get to bitter/sweet news in the policy world.

Bitter, because the CLB is one of the most important, yet least talked about, developments in the last decade to expand equality of opportunity in post-secondary education. For those who qualify the ”œbond” provides an unconditional grant of $500 up front, and $100 for each qualifying year thereafter up to a maximum of $2,000 per child beneficiary once they reach age 15. CLBs are credited to RESP accounts for children of families qualifying for the National Child Benefit Supplement (a taxable child benefit available to low-income families).

Yet, since its inception in 2004, a significant proportion of eligible families have forgone the CLB, either because they didn’t already hold an RESP account or did not apply for the grant. Though participation has risen in recent years, the last estimate by Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) in 2014 showed that participation was still low, at just 32 percent. Though ESDC does not report numbers on CLB take-up by demographic group, research by the NAFC shows that many aboriginal service organizations and their clients are unaware of the program. This likely is true of other vulnerable populations.

This is where the coalition comes in. With the scale of NAFC and its partners there is much potential to raise the profile and use of the CLB among aboriginal populations, and by extension, help close the education gap between aboriginal and non-aboriginal Canadians. This is really great work.

While I applaud the bold leadership these non-governmental actors are showing to help address the under-utilization of the CLB, we need to be asking ourselves: why have we allowed so many families to go without their entitlement in the first place?

This all comes back to design. ESDC administers both the NCB Supplement and the CLB (among other policy initiatives designed to promote child and educational development). Through data provided to them by Canada Revenue Agency, they know who qualifies for the CLB. So why do we place the onus on families, many of whom may have low levels of financial literacy, to:

- know about the free-money;

- open an RESP account; and

- apply for the bond(this only has to be done once).

It doesn’t have to be this way. For political parties in search of a good, practical idea to help reinforce ”œfairness” and social mobility, a simple and relatively inexpensive thing we could do is fix the CLB.

How it works today

Today, ESDC begins tracking a child at the time a family receives an NCBS payment. For each year they are eligible the department attributes money on paper to the child’s name so that when a parent has fulfilled the necessary conditions to receive the CLB (opened an RESP and applied for the bond) they get a payment that is up to date. As families continue to receive NCBS payments after the CLB is first claimed, additional monies are paid into the beneficiary’s RESP (you only have to apply for the CLB once).

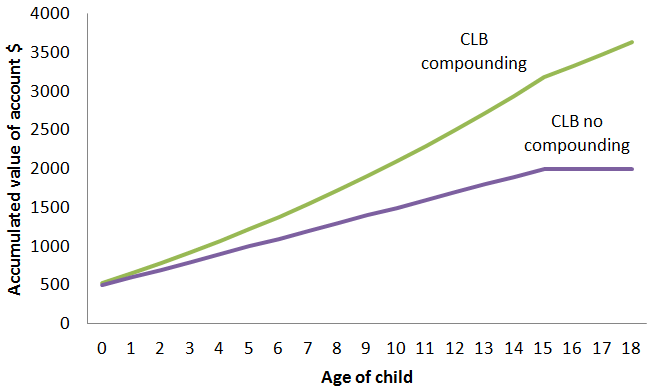

While this at least ensures that families don’t miss out on past years, two problems remain. First, for those who do eventually claim it, the CLB pays no interest, meaning families lose purchasing power and the potential to compound their money over time. Over the course of the child’s life the amount of money forgone can be quite significant, especially if parents wait until their child is just about to finish high school before planning how they will pay for PSE.

To illustrate, consider a family who qualifies for the NCBS each year until a child turns 15, and the potential real return they might get in the market, assuming a compound growth rate of 4.5 percent (currently +225 basis points over a 10 year government bond yield).

A family that opens an RESP at the time of birth and begins collecting CLB payments almost immediately will have nearly $3,200 by the time the child reaches 15, and over $3,600 by the age of 18. This may not sound like much since the CLB is still relatively modest, but it is still about 60 and 80 percent higher, respectively, than what a family would receive if the family delayed their CLB claim. Combined with small contributions from families over time there is great potential here.

Figure 1 – Cumulative value of CLB with and without compounding

The second, and more critical problem, is that families miss out on the benefit entirely if it is never claimed.

What to do

If we already know who qualifies, then the critical problem is ensuring there is an RESP account to which this money should be directed, a small but important step that separates many eligible families from receiving CLB support. If we leapfrogged the process by making RESP enrolment automatic at birth, all families would benefit. Those who qualify could begin to accumulate CLB payments from early on in a child’s life, and every child would have access to a saving vehicle for PSE.

To encourage parental use of the RESP the government could make a one-time contribution to accounts, advancing one year’s equivalent of the Canada Education Savings Grant (which matches RESP contributions made by parents). On a broader level this would help signal to parents the importance of starting to save for an RESP early on in life.

There are various ways in which RESP auto-enrolment could be done. One would establish a default account for each child, to which monies from government would be backed with some interest bearing asset, perhaps a long-term government bond. As CLB and other government payments for child education are made, funds would flow into the account and grow over time.

To promote early use, parents would be notified either when they receive the NCBS or at the time of their tax assessment of the account’s existence, and its current funded status (some mechanics to be worked out here). Parents could formally ”œactivate” the account by moving it to a qualified financial institution just as they do today in registering an RESP and then allocate and fund the account as they wish. Tax treatment and de-registration would remain the same.

In this sense the automation of the RESP system is simply a way to help ”œpre-fund” existing entitlements for those who qualify and to help eligible families maximize the value of applicable programs. I am not calling for the federal government to take over the role of financial institutions in actively managing and running RESPs. That should remain for individuals to sort out. Nonetheless, there are a number of things government can do to make the process simpler, while helping parents access entitlements and saving for education sooner.

It is important to remember that Canada already has a fairly generous and progressive student financial aid system, one in which financial barriers play only a modest role in affecting PSE participation. But if we are going to provide financial incentives to promote participation, we need to make sure our policy tools are well adapted to meeting the needs of those who would most benefit from access to learning: those whose families have not previously participated in PSE, who are predominantly but not exclusively the poor.

RESPs are a good program, but have largely been used by middle- and upper-income households. Making RESP registrations universal would likely increase already high-take up among families who earn a good living, but it would also make sure that low-income Canadians have an equal shot at accumulating the resources needed to make the dream of PSE attendance real. This would go a long way to help even the playing-field.

Rather than asking NGOs to pick up the slack, let’s fix the system.