The leading bioinformaticians Kenneth Mandl and Isaac Kohane have an interesting article in Nature Biotechnology with a paradoxical title: ”œFederalist principles for healthcare data networks.” It’s paradoxical because it prescribes a political answer ”” federalist principles of governance ”” for an engineering problem: how to build networks for sharing clinical data to advance medical research. These issues are, I believe, of considerable relevance for Canadian health care reform.

Mandl and Kohane want to build networks of health care organizations that share clinical data to advance scientific research. They argue that

There are tremendous efficiencies to be realized in using these existing data rather than collecting all data de novo for each study.

This idea is closely related to the proposal for a learning health care system that I discussed here and Austin Frakt discussed here. Research data networks are also a foundation of precision medicine, the program to develop medical treatments that can be closely tailored to an individual patient’s biology.

For example, consider the goal of trying to personalize treatment based on a patient’s genetic profile. To get reliable evidence about how treatment effects vary depending on the patient’s genes, we need data from thousands of patients. This could be prohibitively expensive in a conventional genetic epidemiology study. But if in the near future we routinely genotype patients during clinical care, we could study the association between genotypes and treatment outcomes using data we are already collecting anyway.

At first glance, reusing clinical data for research seems straightforward. Modern health care organizations capture clinical data in electronic health records (EHRs). The data are already in the computer, so just use them, right?

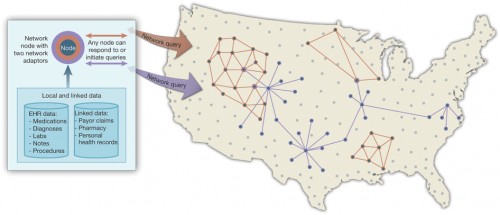

This appealing concept is fraught with difficulty. Scientific research using clinical data often requires combining data sets held by several health care organizations to achieve the necessary sample sizes. So we need to federate data sets, that is, we want to enable researchers to look at data pooled from multiple organizations as if they were one integrated data set.

Federating data sets is a particularly important issue in Canada. A few provinces are developing impressive research data sets, but 15% of Canadians live in provinces or territories of less than 1.5 million people, including the poorest and least healthy provinces. But even Ontario, were it to create a unified research clinical data set, would not have the scale to address many important health questions.

Unfortunately, federating data sets is surprisingly difficult. Different health care organizations follow heterogenous standards in representing variables. Or they make up their own idiosyncratic definitions of common clinical terms. Moreover, EHRs are built to resist access to data by people outside the organization. Part of my day job is analyzing large clinical data sets as an external researcher. Even as a trusted outsider, my connections to these external EHRs are fragile and require lots of inefficient technical fussing.

Thus reusing clinical data for research is in practice a complex engineering task. To federate data across health care systems, we need technologies for mapping diverse data sets to a common representation that is accessible to (but only to) trusted and closely supervised data users.

How should we go about this complex engineering? Mandl and Kohane are clear about thewrong way to do this. Designing a system from the top down and expecting everyone to implement it locally is a recipe for spectacular and expensive failure. In part, this is just the difficulty of large system engineering projects (see healthcare.gov).

But it is also the case that a system that is built from the bottom up by people who actually use it has a far better chance of eliciting behaviors from those users that will sustain and spread the system. Mandl and Kohane argue for self-organizing federated data research networks, which is a fancy way of saying that health care organizations with common research interests should get together and build their own networks.

However, getting health care organizations to converge on common standards is, again, difficult. It’s difficult not just technically but also politically, because you have to forge agreements among large and possibly competing organizations that evaluate every decision against their business models. Successful data networks need feasible governance and positive incentives as much they need workable technology.

To that end, Mandl and Kohane propose federalist principles for federated data research networks. ”œFederalist” refers to political systems based on covenants among sovereign members, where the central authority is controlled by representative institutions. Mandl and Kohane’s principles therefore include transparency about data access rights and control and the representation of participating health care organizations in network governance. They also include economic principles, e.g., that network participation should be cost neutral to and provide local benefit for participating organizations.

The big takeaway here is that the key challenges to building research data networks can’t be solved purely through engineering. We also need governance models that will elicit cooperative behavior from health care organizations. This is exactly the kind of topic that the Premiers’ Health Care Innovation Working Group should be considering.

It’s exciting that leading informaticists are thinking politically. Similarly, we health services researchers should rethink the disciplinary boundaries of our field. How many political scientists or organizational sociologists participate in CAHSPR? The challenges of building a federated research data network are analogous to those faced by, say, the founders of the European Community. Our field could benefit from experts who have studied how decentralized organizations succeed or fail in governing themselves.

(A US version of this post was published at The Incidental Economist.)