The year 2015 has the potential to be a pivotal 12 months for international development. This year, the world reaches the target date for the 15-year-old Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). In September, the UN General Assembly convenes in New York to agree on their successors – a new set of ”˜sustainable’ development goals (SDGs) for 2030. Just beforehand, in July, governments will gather in Addis Ababa to make financial pledges to support these SDGs. And in December, the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP21) convenes in Paris to strike a new deal on actions to prevent global environmental disaster.

In my feature article in the Spring/Summer issue of Global Brief, I argue that the internationally-shared objective of making poverty history by 2030 will require massive increases in private investment, not just public aid. There’s no scenario under which aid alone can do the job. I outline some practical options for mobilizing more private investment in the lowest-income countries that currently see few capital flows and for stimulating greater poverty-reducing business engagement in emerging markets that still harbour large pockets of extreme poverty. Canada could lead by following through on International Development Minister Christian Paradis’ interest in creating a Canadian development finance institution or mechanism (DFI/DFM) to support financial partnerships between the federal government and private capital.

Some brief excerpts from the article lay out the numbers involved:

Estimates of the extra annual financing required to reach the SDGs range from US$500 billion to US$3 trillion on top of what is already being spent on the MDGs. This range hinges critically on whether one includes in these numbers climate change-related spending and a host of big infrastructure projects. Official development assistance (ODA) from governments will never on its own cover these sums. Projected to hit about US$150 billion in 2015, or US$125 for every one of the roughly 1.2 billion people living in extreme poverty, ODA is not even in the ballpark of these cost estimates. Even if every OECD country decided to meet former Canadian prime minister Lester Pearson’s vaunted goal of raising aid to 0.7 percent of GNP (only five OECD countries are currently at this standard) and to realize other unmet commitments, annual ODA flows would still total only about US$350 billion – some US$200 billion higher than current annual disbursements. Aid from new donors – the BRICS and Persian Gulf countries – is increasing, but these flows only partially offset reductions from established donor countries. In short, there is no plausible scenario under which aid flows would be sufficiently large to finance a single year of SDG spending.

[…]

Public money remains crucial, but it will not be sufficient to hit the SDGs. Aid could provide an additional US$200 billion per year; innovative financial levies could add US$1 billion at most; and improved tax collection and reduced tax evasion could yield up to US$225 billion in additional public financing. Pooled funds like the GFATM might mobilize further monies. And yet, at just over US$425 billion in new resources, public money would still not hit even the lower estimate of additional annual aid needed to reach the SDGs.

The full article can be found here.

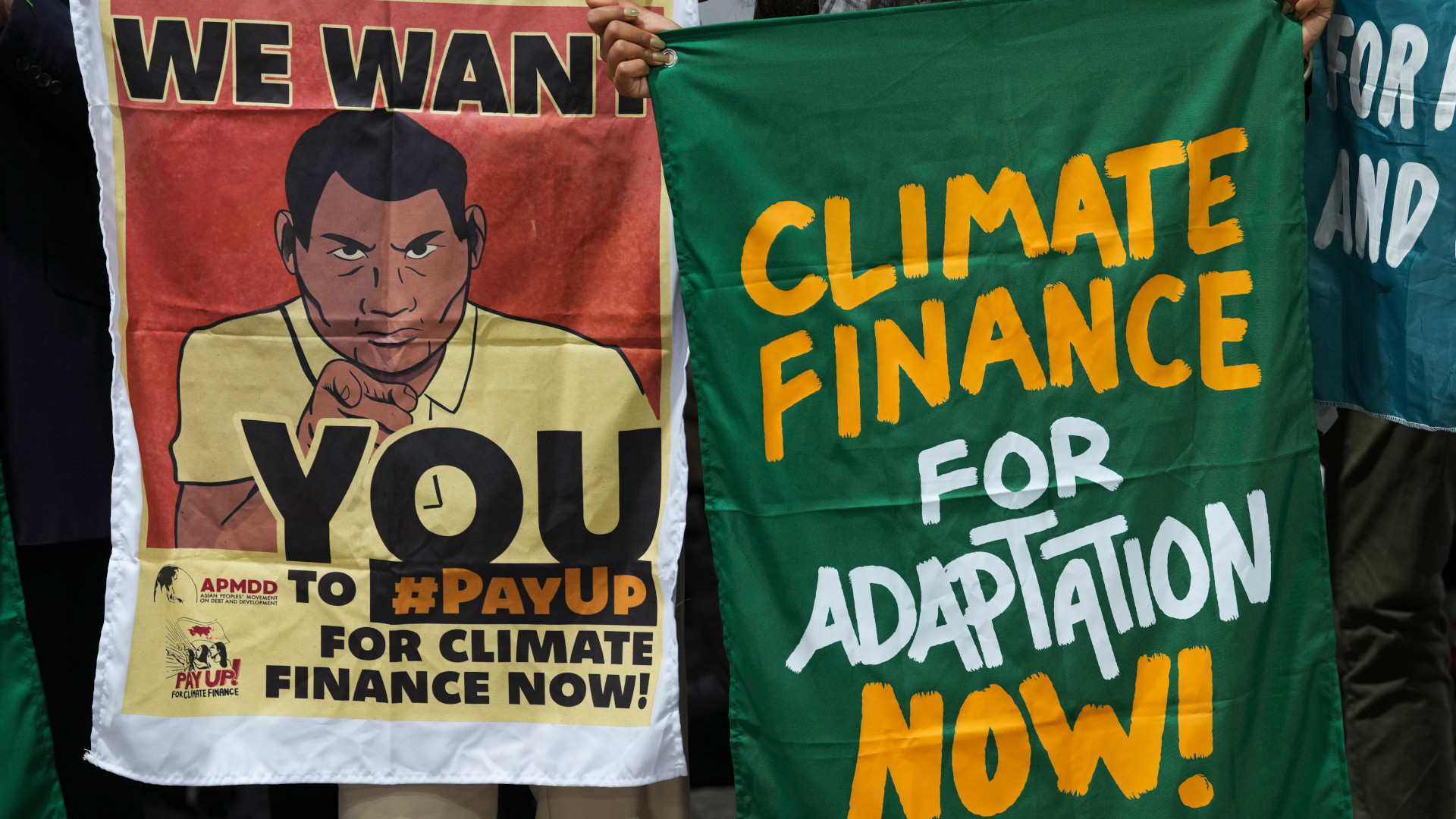

Photo by Gates Foundation / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 / modified from original