There is a perception, repeated often by pundits and embedded in media coverage, that labour mobility is a problem in Canada. Take for example the following quote from a recent, rather provocative, op-ed by Phil Cross in the Financial Post: ”œPeople know where the jobs in Canada are, but a large majority of Canadians won’t relocate for a job. That’s the real problem, and its solution is not more data but getting people to move.”

Labour mobility is important because it reflects the ability of a labour market to adjust to structural changes in demand, to appropriately match workers with jobs that reflect their skill, and to support overall productivity and rising standards of living.

In public discourse, the ”œproblem” around labour mobility is often presented as two-fold: 1) provinces have been slow to harmonize occupational regulations and licensing regimes, creating substantial barriers to people moving between provinces within the same profession; and 2) people are simply unwilling to move, because of some combination of inertia, cost, or entitlements which hold them in place.

The first concern is a very real issue on which progress toward comprehensive reform has been challenging, particularly within the area of apprenticeships and trades. The fact that Statistics Canada finds that Canadians employed in ”œinfrastructure trades” move less between provinces than university-educated workers is a vivid illustration of the problem. Examples of regional cooperation in the West and Atlantic Canada are emerging to harmonize apprenticeship and licensing systems, and provinces seem interested in collaborating on a renewed agenda for Canadian internal trade. Regardless of the size or scope of this issue, we need to remove all the barriers that exist to nationally integrated professions.

As for the second ”œproblem””” whether there is a more general issue of people being unwilling to move ”” I don’t think the diagnosis fits reality.

The fact is that while the proportion of Canadians who move across provinces has been declining over the last several decades, it is not true that a ”œlarge majority” are categorically opposed to the idea of moving for work.

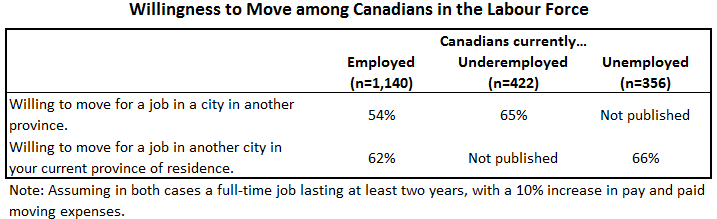

In the 2014 Canadians on the Move survey sponsored by the Canadian Employee Relocation Council, pollster Ipsos Reid tested the willingness of respondents to move based on a variety of scenarios and incentives. The results are highly informative. When you exclude the sub-sample of the population which self-identifies as retired/out of the labour force (and is therefore unlikely to need to move for work), a much different picture takes shape than that which is advanced in the media. Consider the results of the baseline scenarios, which are reproduced in the following table (question wording is paraphrased) and focusing only on those groups in the labour force.

Table 1

Source: Adapted from Ipsos Reid / CERC (2014)

We need to know more about what holds back Canadians from being open to a work-related move, but those numbers suggest that for employers looking to fill vacancies there is a wide, national labour pool at their disposal. The key is that they can’t just expect workers to come to them. As in any textbook labour market, wages and incentives matter.

For firms which report difficulty finding workers, we also need to know how they are responding to these pressures. Are they raising wages? Investing in training? Adjusting work arrangements? How far and wide are they searching for labour? What is the quality of candidates who have come forward? Unfortunately, for too long we just haven’t had sufficient data in order to answer these questions.

New surveys announced by Jason Kenney earlier this month are an important bridge to these answers. What comes of this data will be quite telling.

Before we get too caught up in the quantity of movement, two other points are critical to keep in mind. First, it is possible that what may explain the long-term decline in inter-provincial movement is simply the natural extension of several factors:

- demographic and compositional changes (including the increasing prevalence of dual-earner households),

- technological forces that make it easier to do work remotely, and

- changes on the demand-side, most especially: the stability of jobs, how firms choose to recruit externally when needs arise, and the returns to occupational and geographic changes.

To quote from a new paper by a pair of researchers at the U.S. Federal Reserve and the University of Notre Dame, drawing tentative conclusions about the United States’ situation:

”œIn short, the most plausible reasons for the dual declines in geographic mobility and labor market transitions are ones that indicate a diminished benefit to making such transitions, not a higher cost of doing so.”

Lastly, we have to be really careful how we talk about labour mobility. The structure of the data masks a lot.

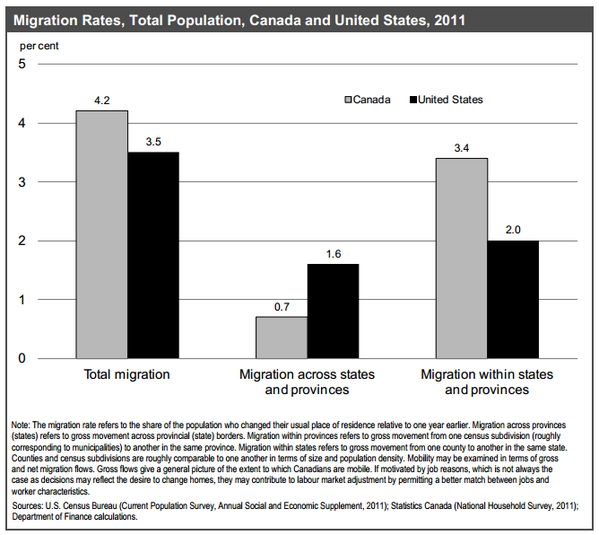

Because we typically restrict the measurement of labour mobility to the provincial level we miss a lot of other movements. In a country as geographically large and diverse as Canada, it is important to know whether someone is moving from Thunder Bay to Toronto, just as much as from Ottawa to Gatineau. When we do this, we find that total mobility in Canada is actually higher than in the United States, where state-to-state boundaries are much closer.

Chart 1

Source: Finance Canada (2014)

Add to this the recent innovation by the government of Alberta and Statistics Canada to better understand anecdotal evidence of people in Atlantic Canada shuffling back and forth between their families out east and work in Fort McMurray. With the help of new data linkages, Statistics Canada has found that as much as 6% of Alberta’s employment in 2008 (as reported by tax data) was living elsewhere in Canada, while nationally more than 450,000 people were engaged in such arrangements. None of those workers would show up in our conventional labour mobility statistics, which otherwise require a physical change in address.

So do we have a labour mobility problem?

There are certainly issues with credential recognition and harmonization that need to and are slowly being addressed.

As for what happens to workers, we should trust that a lot of effort goes into finding jobs and arranging lives to get and stay employed. Lots of people are willing to, and do, move in order to work.

The key, as always, is to make it pay.