Many people want better data in Canada. They think it can improve the quality of decision-making ”” and most importantly ”” outcomes. This group includes Don Drummond who recently wrote this report on how to improve labour market information, and my IRPP colleague Tyler Meredith.

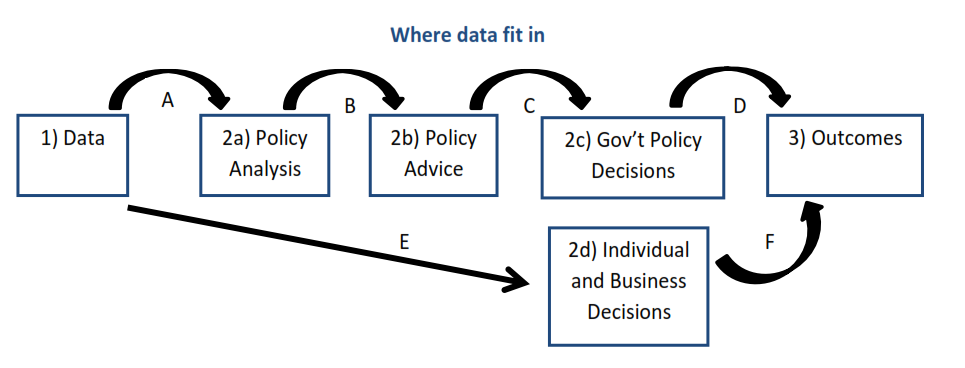

Here’s one way to think about the role of data (shown at Stage 1 in this diagram), and how it might affect outcomes (Stage 3 at the end of the chain). Better data could improve the analysis, advice and decision-making by governments as well as businesses and individuals. Better decisions could then improve outcomes.

It looks like a straight-forward process, but my diagram glosses over important issues. What happens at the arrows in between the boxes. Which data improve analysis? What if more data add complexity that slows down analysis when timely decisions are needed?

And things only move in one-direction in the diagram, from left to right. In reality, things occur simultaneously and there’s feedback from right to left.

Maybe a decision-maker already knows what they want to do and then looks for evidence to justify their priors? Perhaps the outcomes themselves, or developments like technological change or evolving business practices mean new data are needed to understand what’s happening.

A recent op-ed by Philip Cross (a Fellow at the MacDonald-Laurier Institute) raises some related issues. He argues quite provocatively that we need to break our data addiction and reject the natural belief that data, on their own, solve problems. We shouldn’t assume that data make the world more understandable, decisions less risky and the future less uncertain.

These views are particularly interesting given their source: after a long and distinguished career at Statistics Canada it appears that Mr. Cross, who has seen the sausage-making of data first-hand, is now a vegetarian.

He writes that, ”œ…society strives for evidence-based policy. But what is the evidence that more data always leads to better policy analysis?” This is arrow A in my diagram above, but note two important distinctions.

In his article, Mr. Cross argues that more data doesn’t always lead to better analysis. Of course that’s true, but it refutes an argument no one made. Instead, what most data advocates think is that better data will generally improve our understanding of the world. We will make better decisions because of this, and we’ll be better off for it.

Where Mr. Cross wants less data-dependence, Lucas Kawa (Editor of Business in Canada) wants more clarity on the nature of data-dependence in a different context, when he says, ”œwe have… a central bank with a data-dependent stance failing to clearly indicate which data it’s looking at.”

Unfortunately, neither demand is realistic. I worked at the Bank of Canada and alongside hundreds of economists, we collectively turned raw data into analysis and advice (arrows A and B above). The Bank and other institutions analyze as much information as they can gather. They get it from a variety of sources far beyond Statistics Canada, and they filter it through various statistical models and many economists’ brains to generate their best policy analysis and advice.

Instead of this complex process, consider how many central bank watchers would prefer to know with certainty that monetary policy will tighten if, and only if, inflation hits X% or the unemployment rate drops below X%. The world is too complex to be reduced to one or two summary data indicators. Indeed, this is why we need the hundreds of analysts to do their work in the first place.

Both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England recently tried giving markets a simple data rule for their policy decisions. It failed. The problem is that simple rules are too simple, and they come at the steep cost of removing discretion and judgment from decision making. Such tacit knowledge is hard to communicate, but it’s where important value-added lies in this process.

****************

Being data-dependent doesn’t mean responding to every wiggle in data. Nor does it mean basing our decisions solely on data or models and nothing else.

We need better data. But that’s only a start. We also need to ask precise and well-articulated questions ”” not only of ourselves in our analysis, but of our policymakers in their choices ”” particularly in a world where « big data » increases the availability of non-conventional data sources. Moreover, we need to bring new approaches to bare on data, and clearly explain the results to non-specialists.

After concerns about jobs estimates during the Ontario election, let’s hope that the lesson learned by our politicians is not to withhold economic policy analysis in future campaigns. Instead, let’s hope it causes them to raise their game by presenting more credible analyses.

At the same time, let’s be realistic about what can be accomplished with better data. This means acknowledging that data give us imprecise measurements of reality; but when used responsibly and creatively, they help us make better choices and hold governments to account for their policy decisions.