The UK’s Houses of Parliament, also known as the Palace of Westminster, are in dire need of refurbishment. The palace is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site and its infrastructure, updated through the decades, has been falling apart since the building was reconstructed in the 19th century. Earlier this year, the House of Commons flooded during a debate, a “football-sized lump” recently fell off the Victoria Tower, asbestos is widespread throughout the building and fire wardens patrol the building 24 hours a day to mitigate the great fire risk. Similarly to Canada’s rehabilitation of its parliamentary buildings, a Restoration and Renewal Programme (R&R) is planned for the Palace of Westminster to tackle these issues. The R&R programme, however, is due to address only the crisis of the building — not the broader crisis of UK democracy.

The current political upheaval, widespread frustration and anti-politics sentiments in the UK cannot —and should not — be ignored in the design process for R&R. The Hansard Society’s latest Audit of Political Engagement informs us that 72 percent of the public believes that our system of parliamentary government needs “quite a lot” or “a great deal” of improvement. Involving the public from the very beginning, in a positive and confident conversation, would ensure the best opportunity for meaningful engagement between the public and the future of its democracy.

At present, the opportunities presented by R&R to create this meaningful public engagement are mostly being ignored by those in charge of the project — similar to concerns expressed during the Parliament Hill renovation in Ottawa. The promise and potential of R&R therefore risks being impaired by the apparent unwillingness of politicians to acknowledge the political and democratic implications and opportunities of the project. By ignoring the significant positive possibilities that public engagement offers, politicians risk creating a trap that results in the failure of ultimately delivering a Parliament that is fit for the future.

The goal should be to cultivate a genuinely open conversation about the manner in which the shape of our buildings shapes our politics – and the extent to which change might be required.

A Joint Select Committee noted that “renewal brings with it an opportunity to shape Parliament by listening to and harnessing the views of the views of the general public” and recommended that public engagement form an integral part of the proposed legislation establishing the governance structure for R&R. The government’s response instead recommended that the R&R’s external relations body should “consider how the public can be engaged to understand the R&R programme” [italics added for emphasis] rather than ensuring its place (and accountability) in the legislature. Simply encouraging the understanding of R&R will not encourage a meaningful discussion about the future of the palace and the people’s democracy, and suggests a top-down approach to engaging with the public. Instead, the goal should be to cultivate a genuinely open conversation about the manner in which the shape of our buildings shapes our politics – and the extent to which change might be required.

Public engagement with major infrastructure projects has proven to be important to their success. For example, in 2017 the Whitehall thinktank The Institute for Government recommended that the government should create a new organization to involve the public in major infrastructure projects, as it would be “an extremely cost-effective way of giving local communities a genuine opportunity to shape infrastructure decisions” and that it would help “to deliver major projects faster and more efficiently.”

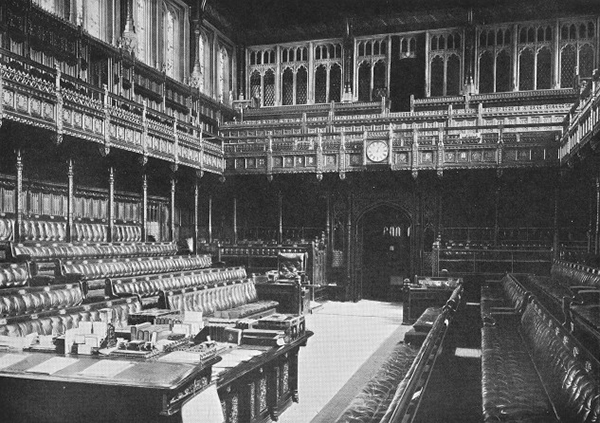

While the House of Commons Commission did hold a public consultation recently, on work linked to the R&R programme (a refurbishment program on the parliamentary estate known as the Northern Estate Programme), we have argued that this approach is minimal and perhaps tokenistic. Part of the Northern Estate Programme includes the creation of a temporary Commons chamber to be used while the Palace of Westminster is completely decanted during R&R. The consultation did not, however, ask about the chamber directly, and instead asks about the possible facilities that could be available around the chamber, or the three possible options for railing designs around the estate. Images of the proposed chamber show one that is a near replica to the original, suggesting that this is no opportunity to experiment with new layouts or to explore different design options and ways of doing politics. Instead, as the consultation openly stated, “the temporary Chamber has been carefully designed to replicate the familiar character and layout of the existing House of Commons Chamber.”

The design of the Commons chamber, and Palace of Westminster in general, dates to the mid-19th century and it promotes a very specific way of doing politics that fails to be welcoming to, or even representative of, a great proportion of the public. The palace was designed by 19th-century gentlemen and for 19th-century gentlemen. As Joni Lovenduski stated in her classic book, Feminising Politics (2005), “for a long time Westminster was one of those places where men gathered with other men. Its ways were the ways of the gentlemen’s clubs and public schools.” R&R could therefore address the longstanding significant issues with the current structure, rituals, traditions and behaviours that exist within Parliament, and it offers the opportunity to open up Parliament to the people it serves.

However, the recommendations on R&R in professor Sarah Childs’s 2016 report The Good Parliament appear to have been largely ignored despite the opportunities they present for a more inclusive, modern democracy. Instead, the current approach to public engagement demonstrates that the government views R&R as an opportunity to restore and protect the past rather than embracing any positive vision of the future. In this sense, the emphasis has been on restoration, and not the important opportunities for renewal.

The promise of R&R is that the program could be used to help close the gap that appears to have emerged between the governors and the governed. While R&R has a primary objective of protecting the physical infrastructure of the building, an open, positive conversation could command public confidence and help address the increasing socio-political pressures, and deliver a Parliament that is fit for the future. In order to ensure success, Westminster needs to regain its confidence and prove that the value of democratic politics far exceeds the cost of maintaining the building even during a time of national austerity. The R&R programme risks falling into a trap of its own making and could fail to deliver on its undoubted promise unless a central vision and a confident political foundation are put into place – with public engagement embraced as key elements of both.

Photo: Students take part in a demonstration against climate change during a Friday Global Climate Strike closing Westminster Bridge, with Westminster Palace in the background, in London, on March 15, 2019. EPA/NEIL HALL

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.