(Version française disponible ici)

When it tabled its budget last April, the federal government proposed a major reform of capital gains taxation, effective June 25, 2024. Quebec has aligned itself with this change.

What is a capital gain? It is the income received by a taxpayer who sells an asset for more than its acquisition cost. This is a form of deferred taxation: the taxpayer sees their asset value appreciate each year, but all these improvements in their economic situation are not taxed until the asset is sold or transferred.

To account for inflation, only a portion of the capital gain income is added to taxable income. This capital gains inclusion rate has been arbitrarily set at between 50 per cent and 75 per cent since 1972.

For individuals, the proposed reform involves increasing the capital gains inclusion rate from 50 per cent to 66.67 per cent, but only on the portion of the annual gain exceeding $250,000. While the tax tables already contain income brackets, with the reform, the capital gains inclusion rate also contains a tiered structure. The reform also implies a move to a 66.67 per cent inclusion rate for all capital gains realized by corporations.

But who are the taxpayers affected by this capital gains reform? How many are they? How high are their gains? Where do they live and how old are they? To get a clearer picture, the Chaire en fiscalité et en finances publiques (the research chair in taxation and public finance) at the Université de Sherbrooke has examined the gains declared during the 2019 tax year. The analysis, which focuses on taxpayers with gains of $250,000 or more, is based on tax micro-data drawn from actual Canadian tax returns from the Longitudinal Administrative Databank (LAD). The latter is a weighted sample representative of the tax-filing population which includes children who receive child benefits and non-filing spouses (and corresponds to 96 per cent of the Canadian population).

Concentrated gains

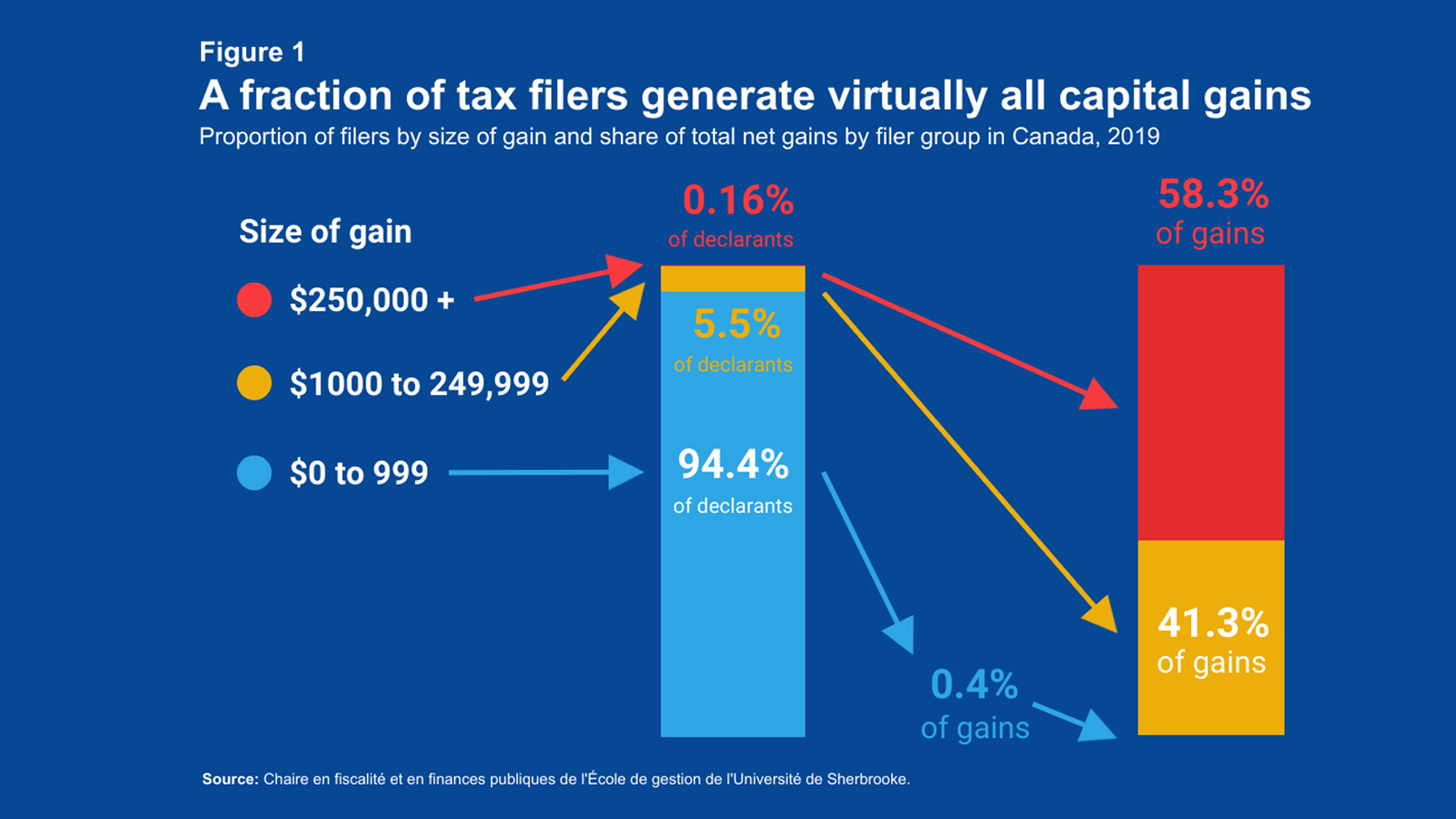

Of the 28.7 million taxpayers who filed a return in 2019, an overwhelming majority (94.4 per cent) had no capital gain or only a small one of less than $1,000. Nearly 5.5 per cent realized more substantial gains, but still below $250,000. Only 46,705 taxpayers, or 0.16 per cent of the total, realized a gain of $250,000 or more.

Capital gains are highly concentrated. The 0.16 per cent of taxpayers with a gain of $250,000 or more accounted for 58.3 per cent of capital gains. If we add up the middle ($1,000 to $249,999) and upper ($250,000 and over) categories, we see that less than 6 per cent of tax filers realized almost all (99.6 per cent) of the gains.

Individuals realizing a capital gain of $250,000 or more reported an average individual income of $1,183,157, or $275,927 excluding the capital gain. By comparison, individuals with medium-sized gains (between $1,000 and $249,999) had average annual incomes of $110,949, or $91,840 without the capital gain. Finally, those with modest, zero or negative capital gains had average incomes of $48,609, or $48,597 without gain, as detailed in Table 1.

Individuals with high capital gains therefore tend to report very high incomes, even when their gains are excluded from the total. This type of income also occupies a much larger share of their income than groups with smaller gains.

In addition to the concentration of capital gains, it is also possible to determine whether there is a difference according to gender, age, place of residence, or even the fact of having died during the year.

Greater gains for men

As with income in general, men’s capital gains tend to be larger than those of women. Among taxpayers with large gains of $250,000 or more, the difference in value between gains realized by men and those realized by women is 28 per cent ($1,020,642 vs. $733,234). Women are also under-represented in this category: while they make up 52 per cent of all taxpayers, only 39 per cent of taxpayers with large gains are women.

Higher earnings among seniors

Unsurprisingly, taxpayers aged 34 or under account for 27 per cent of all filers, but realize only 4.5 per cent of capital gains. Those aged 35 to 64 account for 49.6 per cent of tax filers, and the value of gains they realize is roughly equivalent, at 49.8 per cent of the value of gains. Finally, people aged 65 or over account for 23.4 per cent of filers, but the value of their gains, at 45.7 per cent, is almost twice as high as their population weight. These results are consistent with the idea of capital gains taxation as a tax on deferred income: the older the person, the greater the likelihood that his or her assets have accumulated value that will be taxed all at once upon disposition.

Lower gains in Quebec

Among taxpayers with gains of $250,000 or more, the average gain was $907,327. Ontarians and British Columbians were the only taxpayers with an average gain above the national average ($975,907 and $1,014,686, respectively). This greater dispersion in Ontario and British Columbia could be explained by the strength of the Toronto and Vancouver real estate markets. Taxpayers in other provinces had gains in the $800,000 to $880,000 range. With an average gain of $766,000, Quebec is the only province where the average gain realized by taxpayers declaring a gain of $250,000 or more is below the $800,000 threshold.

More gains for the deceased

Canadian tax legislation provides that individuals realize their capital gains upon death, whether or not there has been an actual sale or transfer. As a result, taxpayers who have died within the year, even though they represent only 0.78 per cent of all tax filers, nevertheless account for 13.7 per cent of taxpayers with capital gains of $250,000 or more. Their chances of having a significant capital gain are therefore twenty times higher than those of the non-deceased.

The second and third articles in this series on capital gains reform will look respectively at the recurrence of large capital gains, and then at the tax revenues expected from the reform and the contribution of the deceased.

A more detailed version of this three-part analysis is available on the website of the Chaire en fiscalité et en finances publiques (the taxation and public finance chair) at the Université de Sherbrooke.