Language issues are never far beneath the surface in Quebec, but the updating of the Charter of the French Language – Bill 101 – has brought them back to the forefront of public debate. François Legault’s government is justifying the new measures in Bill 96 by citing the decline of French in the province, while others are arguing that French is simply not threatened.

One thing is missing from the debate: What is the opinion of Quebecers about the status of French in the province and the relationship between anglophones and francophones? And how has this opinion evolved over time?

At first glance, the situation looks different than it did during the great language debates of the 1970s. Quebec is emerging from the pandemic in relatively good economic shape: the unemployment rate is currently lower in Montreal than in Toronto, Calgary or Vancouver, and Quebec productivity has caught up significantly. In addition, a generational shift is changing the political dynamic, as young francophone Quebecers are tending to move away from the nationalist movement.

One might think that these factors would lead to a greater sense of language security, or at least less anxiety than 20 or 30 years ago. But one would be wrong.

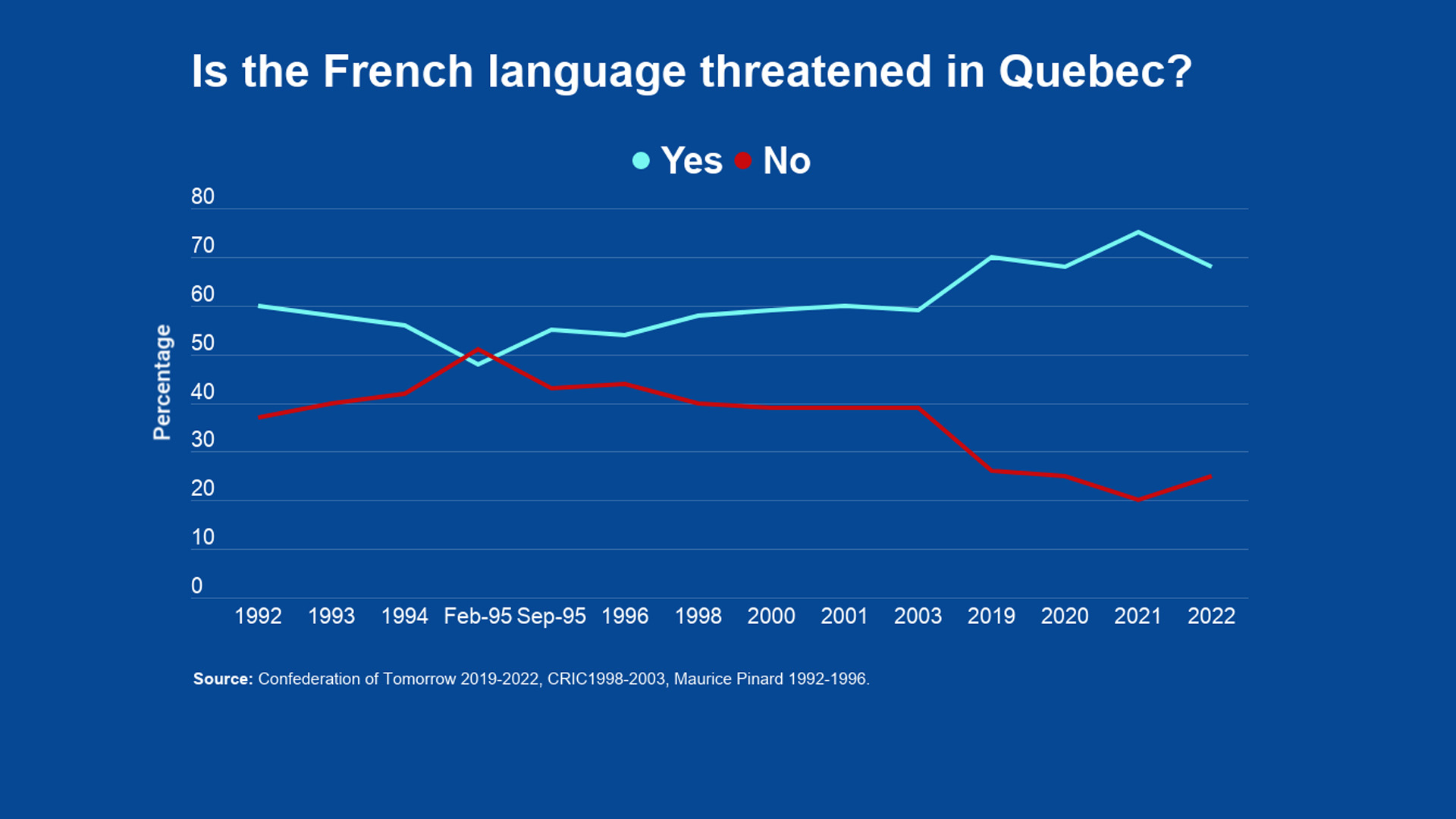

The recent Confederation of Tomorrow survey provides some insight. By asking the same questions in 2022 that have been asked several times in the past, the poll compares the public opinion of French-speaking Quebecers today with over the past 30 years. The results are particularly enlightening.

Francophone Quebecers more concerned about the status of French

When francophone Quebecers are asked if the French language is threatened in Quebec, the signal is unequivocal. As Figure 1 shows, nearly seven in 10 francophone Quebecers feel this way (or 68 per cent). This is down slightly from last year, but the past four years have shown a higher level of concern than in the early 2000s or even the 1990s. This means that no matter what the statistics say (the growth or decline of French varies depending on the statistical measurement used), the perception is very real among francophones that French is threatened in Quebec.

Let’s go further and examine the factors associated with different opinions on the language issue in Quebec. Here, our comparison will be limited to 2022 and 2001, since the presence of many of the same questions in both surveys allows us to model the responses and to analyze more precisely Quebecers’ perceptions of the status of the language, particularly by considering socio-demographic factors and opinions on federalism.

Looking at socio-demographic factors, two observations stand out. While the feeling that the French language is threatened decreased with age in 2001, it is rather the opposite today. Concern about the situation of French increases moving into the 55+ age group.

Similarly, university-degree holders were more optimistic about the situation of French in 2001. By 2022, this effect is gone: holding a university degree no longer reduces the likelihood of thinking French is at risk. The degree of pessimism is also higher overall, regardless of education.

Another important change over the past 20 years relates to the perception of federalism among French-speaking Quebecers. Questioning whether federalism has more advantages than disadvantages for Quebec is more strongly associated with the perception that French is in danger in 2022 than in 2001.

Finally, we observe a similar effect on voting. Being a Parti Québécois voter significantly increased concern for French between 2001 and 2022. In 2001, PQ voters were 11 percentage points ahead of Action démocratique du Québec voters in terms of concern for the French language. Today, the gap is 18 points between PQ voters and Coalition Avenir Québec voters (whom we have grouped with ADQ voters in 2001 for comparison purposes, given the ideological relationship between the two parties). The greater concern associated with allegiance to the PQ may be explained by the fact that it now has fewer potential voters than 20 years ago. Those who remain adhere more strongly to the party’s positions than when the party was more mainstream.

Francophone Quebecers do not feel more economically dominated

If French-speaking Quebecers feel their language is more threatened these days than at any time in the last 30 years, they nevertheless feel somewhat more economically empowered.

The proportion of francophone Quebecers who agree with the statement, “In Quebec, francophones are dominated economically by anglophones,” has fallen from 53 per cent in 1991 to 47 per cent in 2022. In fact, this indicator had been stable prior to 2022, with a slight dip around the time of the 1995 referendum, when the number of economically “confident” Quebecers briefly surpassed those who felt dominated. This relative stability is noteworthy in contrast with the response to the previous question on the status of French.

In 2001, age and education made a big difference in how francophone Quebecers perceived whether they were economically dominated by anglophones. For example, the 18-34 age group was significantly more likely to agree with the statement. In 2022, age-related differences have disappeared. The same is true for education.

As noted, Quebec’s economic development has not changed francophones’ perceptions of their place in the province’s economic environment, nor has it lessened their fears about the future of French. The major difference between 2001 and 2022 is that 20 years ago the most highly educated and the oldest were more optimistic than others on language issues. These socio-demographic differences have flattened out: pessimism on the language issue is widespread in 2022.

These findings have important implications for current events. The Bill 96 debate is taking place in a context where the perceptions of French-speaking Quebecers about the threats facing the French language have deteriorated since 1995, the year of the last referendum. Opponents of Bill 21 (secularism) and Bill 96 (language) will no doubt continue their battle in the courts. But those who wish to see the Quebec government take a different approach would also be well advised to consider public opinion in the province and the factors behind it.

Methodological notes:

The results are based on a series of six logistic regression models (one per year, per question). These models allow us to present the impact of each of the factors included in the models (age, education, gender) as average changes in the probability of agreeing with the statement. In other words, we can estimate the impact of moving from the 18-34 age group to the 35-54 age group on the probability of considering that the French language is threatened in Quebec for each of the respondents in the sample, without changing their other characteristics (age, education, voting, etc.). Since moving from one age group to another will not have the same effect for everyone, due to the other variables included in the model, we then average the effect of this change for the whole sample. It is these results that we report in the text.

The authors wish to thank Maurice Pinard, who was a pioneer in the use of these survey questions and in the study of the evolution of Quebec society.