(This article has been translated from French.)

In late May 2021, Canadians seemed to have received a shock when they learned that the remains of 215 children had been found by ground-penetrating radar in an unmarked mass grave next to the former residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia. A few weeks later, in June 2021, a similar operation in an old graveyard stripped of its headstones revealed 751 human remains next to the former Marieval residential school in Saskatchewan. Other sites are being investigated and the list will continue to grow.

The terrible history of residential schools, brought to light by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), which operated from 2007 to 2015, has thus taken on a reality that previously eluded most non-Indigenous people. But the excavations were not ordered by the federal government: they were conducted at the request of the First Nations directly concerned.

What surprised Indigenous people and academic experts was not the astonishment of the majority of Canadians, but that of the political classes. Indeed, the TRC had devoted the entire fourth volume of its report to “Missing Children and Unmarked Burials.” In the report’s 305 pages, the estimate at the time was that of the approximately 150,000 children who attended residential schools, at least 3,200 never returned home. Since then, the figure has been revised significantly upwards; it is believed that at least 6,000 children died in the residential schools. The TRC had also dedicated six of its 94 calls to action to “missing children and burial information.” But so far, the federal government has done little to follow up, continuing its past behaviour after previous commission reports.

The government and the church

The existence of the Marieval residential school cemetery was known. The cemeteries of other residential schools were also known, either because they were official, or because articles or reports had already appeared regarding accidental discoveries. For example, as my historian colleague Catherine Larochelle notes, erosion on the grounds of the former St. Joseph’s Industrial School near Calgary in 1996 led to the discovery of children’s remains in unmarked graves. This story led to the making of a short film in 2014, Little Moccasins, which has been easily accessible on YouTube since 2019. When it was released, this short nine-minute film did not attract any media attention or political reaction.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau demanded an apology from the Pope, blaming the Catholic Church as if he had just discovered the responsibility of its clergy in residential school policy. However, Call to Action 58 of the TRC report, released in 2015, already called for an apology from the Catholic Church, “within one year of the publication of this report.” If Justin Trudeau – or his advisers – had actually read the various volumes of this report, he would have been aware of the church’s role.

Regardless, anyone who has had a modicum of Canadian history in high school should have learned about the importance of Catholic missionaries in the settlement of the land, the creation of hospitals and educational institutions, and the taking over of “Indian Affairs.” This role of missionaries was a fact in New France, and even more so in the 19th century, starting with the arrival in Canada, in the early 1840s, of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a French congregation.

The policy of the residential schools could be summed up in three words: “civilize,” Christianize and educate. In the 19th century and until the late 1960s, it was hardly conceivable in Canada to “civilize” without Christianizing. A good citizen had to be Christian. This history is not so distant. The fact remains that it was the federal government that created and implemented the residential school policy in the 1880s, during one of the terms of Prime Minister John A. MacDonald. It was not until 1996 that the last residential school in Saskatchewan was closed.

It is undeniable that the Catholic Church – which ran 57 per cent of the Canadian residential schools entrusted to various male and female congregations – has a large share of responsibility, which it also shares with other churches. It should be noted, however, that the federal government terminated the agreements with the clergy in 1969 and the schools continued to exist for almost 30 years.

Learning the history of residential schools

Justin Trudeau announced that we must “learn from the past.” To do so, we need to know the past. The first observation that can be made from the reactions of our political representatives is that they know little about the history of their country. We know that the history curriculum in schools must be reformed to include the history of residential schools and the context that allowed and justified their creation. It should include a reminder that, while residential schools for Indigenous people existed in pre-Confederation Canada, the model for the Canadian residential school system was the Carlisle Industrial School in Pennsylvania (an industrial school designed to teach children aged seven to 14 various trades; the model originated in Britain and was designed to “reform” vagrant, beggar and delinquent children).

The school was founded by Richard Pratt, a former military officer and author of the famous phrase “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Nicholas Flood Davin, a Canadian member of Parliament appointed by the government to investigate the U.S. system of industrial schools for Indigenous children, visited the school in 1879, the year it was established.

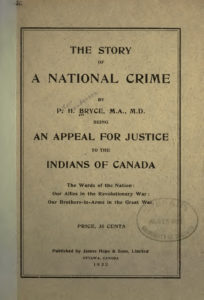

What should also be taught in school is the story of Peter Bryce and why the federal government withheld his expert report. Dr. Bryce was the chief medical officer of the Department of the Interior, which included the Department of Indian Affairs, and was commissioned in 1907 to conduct a study of the sanitary conditions of the residential schools in Western Canada. He found abnormally high death rates in these schools, notably due to tuberculosis, unsanitary living conditions and a severe lack of medical care, and recommended in his report that the government improve its national policies. The report was never published or implemented, but Bryce made it public after his retirement in 1922, which he entitled The Story of a National Crime Being An Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada.

The second observation is that our politicians (and political managers) do not seem to read the reports of the commissions paid for by taxpayers, the same people who elected them to be their representatives. Yet our politicians have staff who can summarize these reports. These commissions are made up of experts who, over a period of a few years, do a colossal amount of work in order to produce valuable, well-informed texts and formulate informed opinions. While not all Canadians would be expected to read these reports, those responsible for receiving them, implementing their recommendations and changing public policy in light of the reports’ expert advice must be familiar with these documents and then orient their programs and policies accordingly.

Today, Canada is facing its colonial history in front of the world’s media. It would have been better if this had been through the implementation of the TRC’s calls for action by the government rather than through dramatic facts disseminated by national and international journalists.

To be better informed about this tragic past, our politicians, as well as any person in a position of authority likely to make decisions that could affect Indigenous people in any way, could start by reading three reports: the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1991-1996), of which Chapter 10 of the first volume deals with residential schools; the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women and Girls (2019), and of course the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015).

In Quebec, one could add that of the Public Inquiry Commission on relations between Indigenous Peoples and certain public services in Québec: listening, reconciliation and progress (the Viens Commission, 2019). At the very least, our politicians would know a little more about the history of their country. Better yet, hopefully, it would spur them to action and to finally implement public policies that take responsibility for Indigenous people and redress past injustices by making real changes in the lives of First Nations, Métis and Inuit people and all Canadians.