Finally, as the political parties start releasing “fully-costed” election platforms, policy nerds have some numbers to analyze!

Quantifying election promises is important work. In theory, it should illuminate, but in practice it mostly frustrates. That’s because it’s difficult — even for budget experts — to assess whether cost assumptions are reasonable, and to compare the parties’ plans in a consistent way.[1]

Jennifer Robson thinks it’d be better, “if we made all parties use common assumptions and reporting for their platforms”. Kevin Milligan agrees.

This is the kind of issue that only The Economist Party of Canada might get behind. It’s a bit like the census debacle: economists get upset about things that make it harder for them to do proper analysis… if we started a petition, I bet we’d get some signatures.

This post explores the idea of trying to get election platforms that could be compared on an apples-to-apples basis, by addressing a few questions:

- If economists could agree that using a common set of assumptions is the right approach, then what might those assumptions be?

- Wouldn’t it be easier if all parties used Budget 2015 as a baseline (even if it’s outdated) and just explained their deviations from that plan?

- What are the pros and cons of having a common approach, not from the parties themselves, but from an independent budget office?

Which economic outlook?

For its economic assumptions, the federal budget uses the average from a survey of Canadian private sector forecasters.[2]

A problem that’s been discussed is that Budget 2015 relies on what are now outdated — and in hindsight, optimistic — economic assumptions, as the outlook for the Canadian economy has deteriorated since March 2015 (when the Budget survey was done).

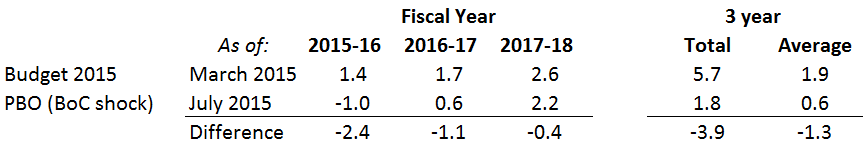

This weaker economic outlook puts the budget numbers in question as a starting point for election platforms. To get a sense at how much the budget outlook has changed, over the summer, the PBO did a quick-and-dirty shock analysis using the Bank of Canada’s July economic outlook. That note[3] estimated that the federal budget balance would be lower by roughly $4 billion over the next three years, or a little more than $1 billion annually.

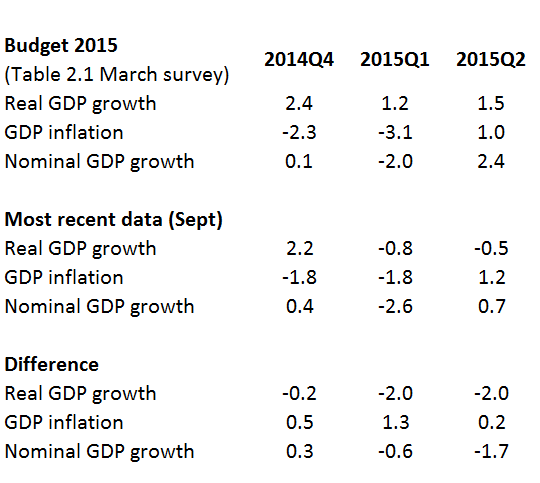

This estimated fiscal hit was much smaller than I (and many others) probably expected. The reason why the shock isn’t so bad is because the drop in nominal GDP — the broadest measure of the government’s tax base — has been smaller than for real GDP. The latter measure, which removes the effects of inflation, is what most economists focus on, particularly when debating whether there was a recession.

(In other words, despite weaker real GDP, the GDP deflator is now higher than expected in Budget 2015, which helps the government’s bottom line. Plus there’s some more fiscal reprieve due to lower interest rates from the Bank’s 25 bps cut in July).

Here’s how the quarterly data have come in so far relative to Budget 2015 expectations:

So this suggests that we could do better than using outdated Budget 2015 economic assumptions for current election platforms. It’s akin to cheating — like adding a line item from Kevin Milligan’s “revenue-” or “cost-cutting fairy” to magically find $1 billion a year (or potentially much more if the fiscal shock is bigger).

So this suggests that we could do better than using outdated Budget 2015 economic assumptions for current election platforms. It’s akin to cheating — like adding a line item from Kevin Milligan’s “revenue-” or “cost-cutting fairy” to magically find $1 billion a year (or potentially much more if the fiscal shock is bigger).

Another problem is that the government hasn’t released its fiscal outlook based on a recent survey, so there is no complete, up-to-date set of budget numbers for the usual 5-year projection horizon. It would help if they did this, but it’s unlikely that they would during an election (and even if they did, people would worry that there was pressure to pad the bottom line.)

So in a second-best world, if all parties used the Budget 2015 baseline, then their bottom lines would all be artificially inflated, but it sort of washes out because everyone is cheating by the same amount, so we can still make comparisons across platforms (even though this raises questions about strict plans for balanced budgets, and we shouldn’t forget that the outlook is too rosy).

Now’s a good time to stress that there really are no “right” set of economic assumptions. Not now. Not ever. There are really just plausible economic and fiscal status quo scenarios, while there are also lots of ways to report implausible scenarios.[4]

Even if each party used the same economic assumptions, their estimates of the fiscal costs and impacts of their proposed policies would be inconsistent and incomparable. Ultimately, it’s important to pick (an admittedly) arbitrary, but consistent, set of rules and use them to construct platforms, but how do you do that?

Should we go Dutch?

The most obvious way to report comparable election platforms is to have parties submit them for scrutiny to an independent, expert budget office. I think that the Netherlands is the only country that currently does this, with its Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (called the CPB).

According to the CPB, the benefits of this approach are that all platforms use the same underlying economic projection. Various proposed programs are then made as comparable as possible. Any wild claims of programs that fund themselves are challenged (“no free lunches”) and otherwise unrealistic costs are amended. Finally, in “the land of coalition governments”, this comparability can help a new government make choices and compromises to implement an agreed-upon budget faster.

But like any system, this can be gamed. This process focuses policy discussions and makes them more concrete, but it also focuses mostly on near-term macroeconomic factors that are easiest to measure. It’s much harder to model bigger, long-term transformational proposals, so this may bias parties to submit more transactional ones. Things that matter but aren’t as easily modeled may be ignored (like, say, distributional concerns).

The final estimates from the budget office would inevitably carry influence in election debates — do we want to leave this job to the “experts”?

This is a time consuming process, which might mean that parties couldn’t make desperate last-minute policy announcement to garner votes (which could be a good thing).

If the parties are free to participate, but are not required to, then the ones that do would benefit from having a more credible election platform (whereas in Canada we now tend to rely on quotes from expert economists like recommendations on book jackets), and those who don’t participate would face more skepticism about their numbers.

I don’t know enough about it to say if the Dutch approach is necessarily better, all thing considered, than the ad hoc approach we have today in Canada that frustrates us policy wonks. It certainly sounds interesting but it’s no silver bullet and presents more trade-offs than you might initially consider.

Incidentally, the issue of costing party platforms was discussed when the PBO was being created in Canada, but ultimately it was not included in the office’s mandate. Perhaps one reason is the problem of overly-politicizing the work of the budget office. Or perhaps the main issue is that it wouldn’t be cheap. In the last Dutch election, the CPB had a staff of over 60 working on this for 3 months. In Canada, the PBO has about 10 economists in total, doing all of the work of the office.

*****

Our current system is a bit like the Wild West. Each party presents their own platforms, with a host of different assumptions. It’s very hard to make informed apples-to-apples comparisons. Simply asking parties to use the same assumptions doesn’t solve the problem because there are so many judgement calls that go into this type of work — and again there are no right answers, only reasonable estimates (for which there would remain healthy disagreement among reasonable “experts”).

If there is any reason for optimism it’s that ‘crowd-sourced fact-checking’ happens much faster in the era of social media. When parties release demonstrably false claims they’re quickly refuted, and lame speaking points are eventually dropped or altered.

Doing a better job of costing election platforms wouldn’t be easy and it wouldn’t be cheap, but I bet that it’s something that the Economist Party would push for nonetheless.

[1] For instance, see on-going attempts by Clark and DeVries here, here and here.

[2] This approach is imperfect — because, for instance, the average of a bunch of forecasts doesn’t always result in a coherent scenario — but it’s been done for over 20 years and it’s defensible, so let’s ignore this point.

[3] Just a word of caution: that analysis was not a formal or full update of the PBO’s budget numbers.

[4] Including the mapping of the economic assumptions into fiscal projections. And I’ll skip the entire discussion of using distributional forecasts, and stick with point estimates.