Let me begin by stating my conclusions and then try to substantiate them—the rhetorical equivalent of dealing cards face up.

My essential conclusions are fourfold. First that Canada is, quite obviously, a one-party state. Other than the Liberals, none of our political parties is a party in the common-sense meaning of that term—that is, a “government in waiting.” They are all factions or splinters or movements. Or they are political devices that particular groups of voters use temporarily for the tactical purpose of drawing attention to themselves. This is to say that most of those Westerners who voted Alliance or Reform, likewise Maritimers who voted Conservative or New Democrat, and Quebec nationalists who voted Bloc Québécois, are not saying that they want these parties to become the government but rather that they want the Liberal governing party to deal with their problems.

Second, that while we are now a one-party state this in itself isn’t new. We’ve always been a one-party state. In the past, though, our one-party state depended on the co-existence of two identical parties—one in, one out—in a kind of Kabuki ritual. The fact that we had two parties, no matter that they were identical, reassured us that we really were a parliamentary democracy able to change our government, to hold it to account, to punish it.

This two-party Kabuki-type game had been winding down for quite some time, as evidenced by the decline in voter turnout, in commitment to and interest in politics, and in attention to and respect for Parliament. But what ended it abruptly is that a serious attempt was made to turn our system into a true two-party system, that is to say a system founded upon genuine ideological differences, or at least significant ideological variations, similar to those between Republicans and Democrats in the US, Labour and Conservatives in Britain, Christian Democrats and Social Democrats in Germany, and their equivalents in just about every other industrial democracy. This attempt, a galvanic and even an heroic one, first by Reform and then by the Alliance, has failed. The consequence of this failure is that we cannot now return to our traditional two-party system (which was in any case really a one-party system). In the meantime, our second alternative governing party, the Conservatives, which historically have been available to replace the principal governing party, the Liberals—in considerable measure because they were so alike it—has been virtually destroyed. What we have now is neither our old system nor the hoped-for new system. We have instead a true one-party system, what could be called an in-your-face one-party system, as a result of which we can no longer pretend that we have a two-party or a multi-party system. We’re worried because this undermines our democracy and because it undermines ourselves, making us look under-developed and immature among the industrial democracies.

My third conclusion is that although our democracy is indeed being undermined by the advent of today’s true, unapologetic, one-party system the undermining is not complete. For one thing, though we lack an opposition party we nevertheless have all kinds of vocal and influential opposition to the governing party. For another thing, some of the factors eroding our democracy, such as the decline in voting, have nothing whatever to do with our one-party status. On the negative side, our one-party state may be less democratic than equivalents elsewhere—Sweden’s Social Democrats, for instance, who are semi-permanently in power—because of political factors either unique to us or at least more pronounced here than almost anywhere else. The overweening dominance of the Prime Minister’s Office is one example. The lack of a tradition of dissent within our parties, above all the governing one, is another.

Lastly, to conclude on a positive note, and hence a thoroughly Canadian one, the widespread unease and even embarrassment about our condition as a one-party state may precipitate a generalized determination to shore up our democracy, both in the form of a recreation of our two-party system and by addressing some of the ways in which our democracy is failing, such as in the dwindling voter turnout.

Now to try to justify my conclusions. The hegemonic dominance of the Liberal Party is the easiest aspect of the affair to demonstrate. It’s never existed on the same scale in our history. Even during the King-St. Laurent reign in the 1940s and 1950s, the Conservatives remained, if relatively small and perennially losing, a potential governing party. Today, they are an official party at all only by the narrowest of margins. In the polls, even after a year of favorable press coverage and of chaos among their rivals on the right, the Conservative standing is only 13 per cent. Perhaps they were pruned too far back in 1993 to ever really recover.

At 51 per cent in the latest polls—an unprecedented measure of popularity for a third-term government—the Liberals would win over 200 seats. But even this robust statistic undermeasures their real strength. They are the second as well as the first choice of most Canadians—by far. They are the second choice of most New Democrats, of most Conservatives, and of a surprising number of Alliance supporters. (Data for Bloc Québécois supporters is not available: their second choice probably would be not to vote at all, but even that would tilt seats to the Liberals). No wonder the “unite the right” project is making such slow progress: most on the right would prefer to unite with the Liberals.

But even after the factoring in of second-choice support, Liberal strength still remains underestimated. The Liberals start each campaign with about half the seats needed for a majority already in their column. This is because they own—and that is the right word—all of the bloc votes in Canadian politics. There are four of these blocs: federalist Quebecers, who account for about half of the province’s 75 seats; francophones outside Quebec, who account for about 10 seats; immigrants, another 30 to 35 seats; and Native people, who in the last election only gave money to the Liberal Party and who can account for up to half a dozen seats. That’s about 75 seats in the Liberal bag even before the race starts.

Because incumbency is of such paramount importance to bloc voters Brian Mulroney might well have broken this iron quadrangle had he won a third term. But even his exceptional political skills could not stave off the ultimate unraveling of his unnatural alliance of Quebec nationalists and Western regionalists.

Never say “never” in politics, which is hyper-volatile these days. Less than a decade ago, in a single election a party went from 200plus seats to two. Dramatic change certainly is possible. A deep recession could do it. So could blunders—such as failing to hide arrogance and smugness.

But for the medium term it’s hard to foresee how radical change should happen. All subsidiary factors favour the Liberals. The turnout is low: governments are only defeated when the turnout is high. Interest in politics is low: to defeat a government, people need to believe that changing it will really make a difference to their lives. Opposition parties are particularly handicapped by low political interest. Their platform and megaphone is Parliament. But so few Canadians pay attention to Parliament these days that very few will notice their verbal victories over the Liberal government. Lastly, the land, economically and in terms of national unity, really does now seem to be strong.

My guess at the medium-term future is that after Jean Chrétien steps down in 2003 Paul Martin will succeed him and, by reassuring Canadians that their national leader is capable and steady but not too demanding or visionary, which is the recipe for political success these days, will secure two more majority governments for the Liberals. That’s as far as it’s possible to peer into the crystal ball. But one additional, depressing, comment must be made, and that is that incumbency reinforces itself. It attracts money and talent because it can reward both. All others starve. The odds thus are that for some time we will continue to experience not just prolonged Liberal dominance, which most certainly isn’t new, but an absence of any alternative “government-in-waiting”, which is without precedent in our history.

This never happened in our old two-party system, which really was a one-party system because the second party, usually the Conservatives, was so alike to the governing one.

I have of course been exaggerating a bit for effect in saying that traditionally—for all the years since Confederation except the last decade—our two principal parties were identical. But not exaggerating by much. The Conservatives gained power in 1957 because John Diefenbaker was more liberal than the then ultra-conservative Liberals. An important aspect of Joe Clark’s success in 1979 was that he was a Red Tory. Brian Mulroney was actually more liberal than his opponent John Turner in his winning 1984 election. Turner spent much of that campaign trying—futilely— to persuade Canadians of the importance of balancing the budget.

This similarity—of a common centrism and pragmatism tinged by liberalism or Red Toryism— is inherent in our political culture. We are not divided by economics. Perhaps we should be, but in politics, perception is all, or almost all, and almost all of us think of ourselves as middle-class, even those at both ends of the spectrum who clearly are not. Instead of income or class divisions, we have regional divisions. We all are Quebecers, Albertans, Newfoundlanders, Saskatchewanians, Nova Scotians, whatever. Since our ideology is regionalism, it’s natural for supposedly opposing parties to be similar. Both are regional coalitions, if from time to time of different regions.

Indeed, the single relatively clear, relatively long-standing difference between our two traditional parties is that the Conservatives have consistently been more accommodating to Quebec and to the provinces in general—from Stanfield’s espousal of “two nations” to Clark’s “community of communities” to Mulroney’s Meech Lake. It may therefore not be coincidence that the Liberals have usually won. There’s an inherent illogicality in a federal party arguing provincial interests, rather than arguing that it “speaks for Canada.”

In the last decade a sustained attempt has been made to restructure our unreal two-party system into a real two-party one based on ideological differences, or variations. In terms of seats and of possession of the status of Official Opposition, Reform and now Alliance have done remarkably well. But their success was always shallow. It was catalyzed as much as anything by fear. In the early and mid-1990s, Canadians were deeply afraid that, because of the unbudgeable deficit, because of rampant down-sizing, our entire economy was unraveling. That fear, while not vanished, is now largely under control. To a considerable degree, Canadians have gone back to being Canadian—centrist, pragmatist, with a reformist tinge. The implications of the fierce attachment of Canadians to one-tier medicare should not be underestimated. Over time, the national centre has shifted. (So, in lock-step, have the Liberals.) Canadians are much more self-reliant than ever before; and there’s now a widespread acceptance of free trade and of the global economy. But we remain very Canadian.

There is, incidentally, one, if not bloc vote then consistently preponderant vote that explains a good deal of the persistence of the Liberals in power. This is that women, disproportionately, vote for them. In the end, Reform and Alliance represent the ultimately very narrow constituency of angry, white men. In other words, the attempt to reshape our political system into a two-party one based on ideology was doomed to failure; Stockwell Day’s contribution was to hasten that inevitable failure rather than to cause it.

This attempt to restructure our political system has nevertheless had a transformational effect. Our old, reassuring, two-party system that was really a one-party system has been destroyed. Standing solitary in the wreckage is the— Liberal—one-party state.

Since, like it or not, we are a one-party state, how much should we dislike it and fear it? Dislike it in and of itself because it is unimaginative and timid. Fear it because a single-party state is, inherently, an undemocratic state. To this question the answer (decisively!) has to be yes and no.

In several important respects, a one-party state is not at all necessarily synonymous with an undemocratic state. None of our municipalities has an official opposition but none is notably undemocratic as a consequence. None of our public institutions, from hospitals to universities, operates along formally democratic lines but all, in different ways, are responsive to internal and external pressure. Perhaps our best-run province, Alberta, has been a one-party state for almost three-quarters of a century, experiencing in that time just one political change, from right-of-centre Social Credit to centre-right Conservative. The Albertan style of democracy has also typically been characterized by weak oppositions in the legislature and by the absence of a tradition of press or public dissent, and yet Albertans don’t seem to be living in an undemocratic society.

More positively, important forms of opposition exist even in the absence of an Official Opposition. The provincial premiers are forever attacking Ottawa, and on a scale for which there are few international parallels. Our civil society is one of the most vocal—the global leader would be the US—and the best-funded not least because interest groups and non-governmental organizations receive so much from the governmental hand they spend most of their time biting. We have developed a fair number of think-tanks of which a conspicuously large number of the best-funded—Fraser, Donner, C.D. Howe, the Atlantic Institute of Market Studies—are extremely critical of the governing party.

Extra-parliamentary opposition can be creative and effective. The entire phenomenon of the anti-globalization movement, which, whether it is right or wrong, has mobilized some of our best-educated and most idealistic young people in a way that no other political activity has done, has happened without any involvement from any political party—or, to be strictly accurate, with only a limited contribution by the New Democrats. More new stimulating and provocative ideas have probably been contributed to the Canadian political discourse in the past half-dozen years than by all the federal opposition parties by just two individuals, Tom Courchene and Tom Flanagan. Earlier, it was Preston Manning personally, much more than the Reform Party, who generated novel political ideas about the deficit and about a Plan B for dealing with Quebec separatism.

More negatively, our democracy is at risk anyway these days for reasons that have nothing to do with our being a one-party state. Even if we became a multi-party state, these factors would still apply. The decline in voting is corroding our democracy far more seriously than has been generally realized. We tend to assume we’re only in relative trouble because while our turnout last time was a low 62 per cent, that in the US was a rock-bottom 49 per cent. But our turnout is actually nearer to theirs than we choose to recognize. We assess it on the basis of votes as a percentage of registered voters, the Americans on the basis of votes as a percentage of eligible voters. About a million eligible Canadians were not registered in the 2000 election. As a percentage of eligible voters, our turnout was only 55 per cent, well within hailing distance of theirs.

Just as perilous is the decline of interest in and commitment to politics. Both are at a post-World War II low, at the very best. Large numbers of Canadians are engaging in the ultimate undemocratic act of ceasing to hold their government accountable, or ceasing to even care what it is doing. And, the less interest there is in politics the more extended will be our one-party condition because only if voters are interested can an opposition party mobilize them to turn out the government. And of course, in a classic vicious circle, the longer we are a one-party state the less interesting is our politics.

All of that was, in one way or another, the good news, or comparatively good news, about the effect upon our democracy of our being a one-party state. Now for the bad news. A reader has provided me with a useful phrase that seems best to fit the condition we have got ourselves into. This is that we are undergoing the phenomenon of “diminished democracy.”

It’s obvious that a one-party state diminishes our democracy. The lack of a persuasive and powerful voice at the centre diminishes our ability both to engage in national debates and to hold those who govern us accountable by threatening them with the ultimate democratic sanction of being removed from power. But our democracy may be diminished even more sharply than in other one-party states because of factors unique to our political culture. We aren’t merely a one-party state. We are what could be called a one-office, one-party state. The party doesn’t really matter that much. The office—the office of the prime minister—matters comprehensively and oppressively. Donald Savoie has described this in his important book, Governing from the Centre. He argues that Jean Chrétien is probably the most powerful leader—the least-challenged that’s to say—in any industrial democracy.

To the distinctively Canadian attribute of our being a one-office, one-party state, I would add that of our being a one-voice, one-party state. To a degree without parallel in the rich countries— most certainly not in the US, nor in Britain, nor in most European nations—our one governing party speaks with one voice. That voice is the voice of its leader, the prime minister. Even after many years covering Ottawa, I’ve never been certain why it is that our MPs and ministers and political officials have always been so timid, so unimaginative, so plainly and simply immature. Career ambitions, and fears, of course. But why the entrenched, almost never-varying docility that makes our one-party state even more suffocating, and even more constipated?

There is a final way in which Canada as a one-party state will be less democratic, not merely than the Canada of the past, but than other countries today. Our system functions on the basis of a permanent, supposedly neutral, certainly meritocratic, civil service that serves the governing party, whichever it may be. Political tenure will increasingly make the civil service and the politicians one and the same. At least anecdotally, this appears to be happening. Today’s civil service, though, is not the civil service that served our quasi-one-party state during the 1940s and 1950s. That civil service was exceptionally creative. Today’s permanent civil service simply lacks the intellectual talent and energy to properly serve a permanent governing party. That governing party, like all of its kind, whether short-tenured or long-tenured, has almost no capacity for generating ideas: these days parties have little purpose except to organize elections and raise funds. Just about the only source of new ideas for the governing party is a leadership convention. And when and whether at all the next one will be held is exclusively the prerogative of the one office within our one-party system.

And now to the question of what can be done to restore our diminished democracy.

First, that there are no snap solutions, such as proportional representation (PR), which is currently popular among academics. It’s true that if PR were implemented, there would never again be a majority government and so no one-party state. But PR will never happen. The Liberals would never propose and then enact the legislation that would end their one-party state. Never. Thus all discussion of proportional representation, however elegant and well-intended, is dilettantism.

Second, the problem itself may generate its own solution. That we are a one-party state has become generally recognized in only the past few months. With recognition has come rising concern. One recent survey found that Canadians believe, by a margin of 62 to 34 per cent, that “Lack of competition in Canadian politics is a problem.” The topic will be given additional attention by two books due to be published shortly—The Friendly Democracy by Jeffrey Simpson and Gritlock—Are the Liberals in Forever? by Peter White. There is concern about our democracy and also an underlying sense of humiliation and embarrassment. Quite simply, Canadians don’t like being told they are so politically impotent that they live in an unchangeable one-party state. Recognition that we are trapped in a situation that undermines our democracy may inspire us to seek ways to revive it.

Restoring a more substantive version of our traditional two-party system would be only one step. The docility of our MPs—in all parties—may come to be regarded as unacceptable. The intellectual emptiness of all of our parties ought to become just as unacceptable. Why on Earth should not issues of the order of importance of, to cite the two most important contemporary ones, integration with the US and reform of health care, not be debated openly and uninhibitedly within our parties and within Parliament? As for Parliament itself, if it is going to become again an object of real interest to Canadians, it is going to have to be reformed in ways that liberate the talents of individual members and make it again a focus of national debate. The one-party state issue entirely aside, this is surely as possible as it is essential for the health of our political system. Campaign finance reform, electoral reform, reform of parliamentary committees, the list of work available and needing to be done is almost endless.

Let me end with this conclusion: A one-party system, simply because it is in-our-face and recognized as threatening to our democracy, could result in our achieving under pressure a far more democratic political system than the genteel, Kabuki-style system that we functioned with for so long. This could happen, that’s to say, provided that we will it to happen.

This is the text of a speech delivered to the Monday Club, Massey College, Toronto, 10 Sept., 2001.

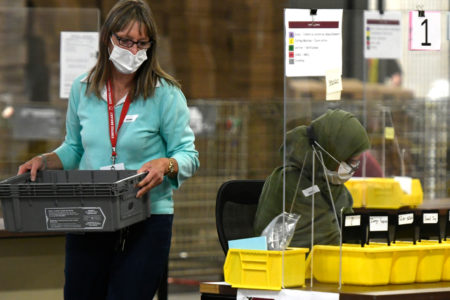

Photo: Shutterstock